Not as easy as my first swarm capture, but just as rewarding.

The bees are starting to swarm. They do it every year around this time. They’ve outgrown their homes and their colonies split. The queen and about 2/3 of the workers leave the hive in search of a new home. They’ll gather in tree branches and on building eaves, resting while scouts look for the perfect place to move in. Sometimes it’s a hollow tree; other times, it’s an empty space in the wall of your home or garage, accessed by a hole so small you didn’t even know it was there. I blogged more about swarms here.

Beekeepers like this time of year. It means free bees. But we have to work for it.

I was called out for a swarm capture the other day. Some new beekeepers met me there — the plan was for them to assist and learn. But the bees flew off right as they arrived.

Yesterday I got another call. I grabbed my bee box — that’s a rolling plastic toolbox I store all my beekeeping equipment in — and a cardboard nuc box with six frames in it and jumped in the truck. The bees were up in a pine tree and I was hoping it was near where I could park so I wouldn’t have to deal with a ladder. That’s how I’d handled my first swarm capture last year.

No such luck. The homeowner met me and escorted me to the back yard. The bees were about 12-14 feet up, gathered in two big clumps on the branches of a pine tree. Beneath them were some huge ornamental rocks and a somewhat neglected rock garden. Even if I could back my truck into the yard, I’d never get it close enough to use it as a platform.

Stan, a new beekeeper, and his wife arrived. Stan seemed very knowledgeable — so knowledgeable that I didn’t realize he was new. I suited up while the homeowner fetched a 12-foot orchard ladder. Orchard ladders are the best for outdoor work in trees; with just three legs, they’re really easy to set up and keep balanced. Stan set it up and it was rock solid. That didn’t make me feel any better, though; I don’t like climbing ladders.

But I wanted this swarm so I climbed.

Stan held the ladder while his wife, on the ground, held one of the tree branches away. While most of the bees were clumped together, hundreds of them buzzed around my head while I dealt with the thick pine branches and needles. Bees are not aggressive when swarming. They have very little to protect — just the queen, in fact — and have gorged themselves with honey prior to departure so they’re a bit on the sluggish side.

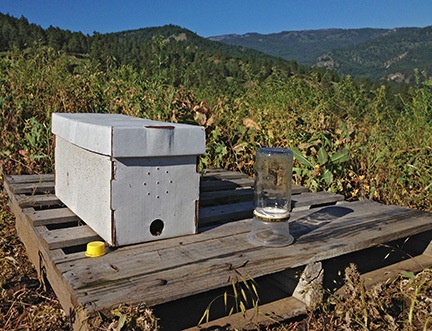

The idea was to cut the branches the bees were clumped on and lower them into the nuc box. I’d already prepared it by removing four of the six frames. The two frames I left in there contained drawn-out comb made by other bees. I was basically offering them not only a new home, but one that was partially furnished.

Trouble was, the big clump of bees, which was probably the one protecting the queen, was on a big branch — so big, in fact, that I needed a saw to cut it. All I had was my clippers. (Note to self: add saw to bee box.) Fortunately, Stan had a saw. He fetched it and I did what I didn’t think I’d ever do: I released the ladder so I could hold the branch with one hand and saw with the other.

12 feet off the ground. Wearing a bee suit complete with pith helmet and veil.

I must have looked comical.

The branch came free remarkably easily. I was going to walk it down the ladder, but Stan volunteered to take it from me. He wasn’t suited up at all. A brave man who understands bee mentality. (I prefer to feel “invincible” in my bee suit while working closely with bees.) I handed the branch to him. It slipped as he changed his grasp on it, dumping about 1,000 bees onto the ground. But then he pulled another frame out of the nuc box and stuck the branch in.

A crowd of spectators had begun to gather, all keeping their distance.

I turned to the other clump, which was smaller. It was gathered on a pair of much smaller branches that intersected. I’d need to grab the branches together and cut them together. No problem. The clippers made short work of them. I descended the ladder holding a branch with about 3000 bees clinging to it. I lowered it into the box.

By this time, the bees had taken a liking to the box. Bees covered both sides of the frame in the box and were climbing up the outside of the box to move into it. They were abandoning the branch to move into the box. Bees were fanning all over the top of the box, sending the queen’s scent out to the other bees so they could find them. Even the bees on the ground were heading for the box. It was pretty amazing stuff.

We started by lowering the branches of bees into the prepared nuc box.

Over the next 20 minutes, we worked to encourage the bees to move into the box. I trimmed away empty branches to make the bee branches smaller. I slid another frame into the box. I lifted the branch and used my bee brush to sweep bees from the branch into the box. Stan slid in another frame. I banged the branch to shake the bees into the box. The whole time, spectators watched, taking photos, getting closer and closer. The bees were completely docile. The ones that knew about the box clearly wanted in.

Eventually, we got them off the branches and into the box. We slid three more frames in for a total of five. I think three of them had drawn out comb and the others were brand new. I left the box open for a while. About 100 bees were still flying around, looking for their friends. They’d never all be in the box. It was time to close it up and head home.

Most of the bees were in the box within about 20 minutes.

I thanked everyone for their help and gave my email address to one spectator who claimed to have video. (I hope she sends it!) I told Stan that now I owed him an assist.

I put the bees and the rest of my gear in the back of my truck and headed out. May 10 and my first swarm capture. It was a good start for the year. Would I have any others? Swarm season ran until the end of June. I have my fingers crossed.