Lots of fog coming and going all day long.

I knew when I woke up yesterday morning that it was going to be a foggy day. How could I tell? I looked out my window and didn’t see a single light anywhere. The fog was all around me, blocking out the thousands of lights down in Wenatchee that keep my home from getting dark at night as well as closer in lights in at my neighbors’ homes. It was pitch black dark.

But with fog and low clouds moving around, it would be a good day for a time-lapse.

The Equipment

I went down into the garage and rummaged around in a box full of old camera equipment until I found my Canon PowerShot G5. This was my first “serious” digital camera, which I bought back at the end of 2003 for aerial photography. (Back then, I had the crazy idea that my future wasband was capable of taking satisfactory photos from the helicopter to meet the needs of aerial photo clients. That turned out to be a very expensive exercise in futility.) With 5 megapixel resolution, it was a big deal — all my digital cameras up to that point had shot in 2.1 megapixels or less. I even took it with me to Supai, the Havasupai village at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, when I went on an Arizona Highways photo excursion in April 2004.

So yes, the camera is old. At least by today’s standards.

But I don’t throw anything useful away. Even when I got better digital cameras — like the Nikon D80 I bought in 2007 and the Nikon D7000 I use now — I kept the old Canon.

Years ago, I bought a Pclix intervalometer for it and started using it as a dedicated time-lapse camera. An intervalometer, in case you don’t know, is a device or camera feature that tells the camera to shoot an image periodically per your specifications. That and a tripod are the two things you need to make time-lapse movie images. You then use an app on your computer (or smartphone, I suppose) to compile those images into a movie.

Shown here: my Canon G5 with optical cable taped on, Pclix intervalometer, and the power supply for the camera, which is not USB.

The Pclix I have uses an optical trigger mechanism. That means it sends a beam of light down a fiberoptic cable. The light is seen by the old Canon G5 as if I’ve pointed a remote at it and it clicks the shutter. To get this to work, I used electrical tape to attach the business end of the optical cable to the G5’s remote sensor. Of course, the camera needs to be plugged into power — its old battery won’t hold a charge and, even if it did, it wouldn’t last all day. The Pclix runs on a pair of AAA batteries and I was very surprised to see that they still had enough juice to power it. But I guess an electronic timer and tiny beam of light don’t need much power.

When I dug out all this stuff yesterday morning, I was kind of surprised to find it all. (Note to self: putting things away really is a great strategy for making them easy to find in the future.) Although I still do time-lapses once in a while, I’ve been using my GoPro, which is a lot more compact and easy to set up. But my GoPros and my Nikon D7000, which has a built-in intervalometer, are all in Arizona, waiting for me to join them. The G5 was my only option.

Setting Up

I’ve always been interested in time-lapse movies. There’s nothing quite like them to show the movement of slow-moving things. You can see the ones on this blog by checking out the time-lapse tag.

Of course, the challenge is to set up a time-lapse camera before something interesting happens. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve tried to create a time-lapse of clouds on days that clouds never made an appearance. The good thing is, the images are all digital, so if a whole day shooting results in a dull time-lapse, I can just delete it all.

Yesterday’s challenge was pointing the camera in the right direction with the right zoom magnification. (This is one of the benefits of using the G5 instead of a GoPro: optical zoom.) It was barely light out and the fog was thick when I got it all set up. I was also concerned about focus; I let the camera’s autofocus feature take care of that, but when there’s no detail to lock in on, the camera can’t focus. So I suspect there are some focus issues with individual shots.

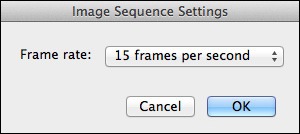

I let it run all day from the corner of my deck, plugged into one of the outlets there, with 1 shot every 15 seconds. That’s how the Pclix was set up. I’d lost the instructions and didn’t want to mess with reprogramming it.

The Results

I checked on the camera at about 3:30 PM and discovered that its tripod had fallen over. Oops. I brought it in and saw that the last shot taken was after 2 PM, so I did get most of the day.

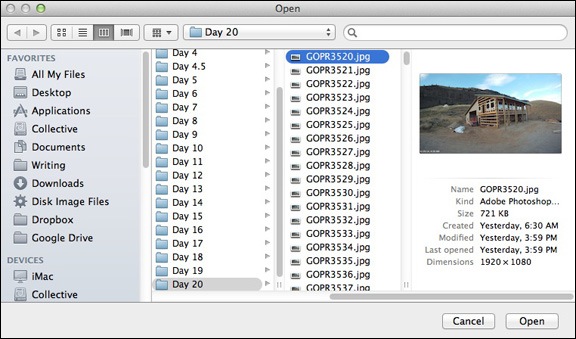

I brought the camera up to my loft where my office is now. It took a while to find a cable that would connect the old camera to my computer — I knew there was no chance I’d find a card reader for the Compact Flash card (which isn’t compact at all by today’s standards). I worked some magic and got the images into my computer.

Then I ran them through an app that resized them and put the time in the corner.

Then I fired up QuickTime 7 Pro — which I’ve always used for time-lapses — and created a movie with 30 frames per second. So each second of this movie is 7-1/2 minutes of the day. Here it is:

What surprises me most is just how much of the day was foggy. Keep in mind that my home sits on a shelf about 800 feet above the river. In the winter, we often get inversions that fill the valley with fog. Sometimes I’m above it, sometimes I’m in it, and sometimes I’m below it. Yesterday, I was mostly in it and above it. At one point, I looked out my office window, which faces south towards the cliffs, and it was perfectly clear. Yet at the same time, the view through the camera was nearly completely fogged in.

Of course, this has motivated me to do some more time-lapses. Maybe I’ll produce a few in Arizona when I head down there for the winter. But I think I’ll leave my clunky G5 setup home.