On what’s likely to be my last aerial photo gig here.

Penny with makeshift earplugs. They lasted about five minutes before falling out.

I flew my helicopter up to Lake Powell late this morning. With me for the ride (and the few days to follow) were a friend and Penny the Tiny Dog.

The Backstory

Way back in June, one of my good clients, Mike Reyfman, had booked three days of aerial photo flights with me starting January 1. He leads photo excursions for Russian photographers in various places throughout the world. I’m his Arizona/Utah helicopter pilot. I’ve flown for him on about a half dozen gigs since 2004: Lake Powell, Horseshoe Bend, Monument Valley, Goosenecks, Shiprock, and Bryce Canyon. Jobs last 2 to 7 days and involve 8 to 20 hours of flying. It’s good work not only because of the number of revenue hours I can fly, but because it takes me to some of the most incredible scenery in the southwest.

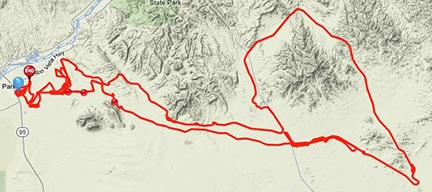

I had mixed feelings about the job. I wanted to go to Lake Powell again; it had been over a year since the last time I was up there. I own a hangar at the airport — purchased back when it looked as if I might do seasonal tour or charter work there — and I wanted to sell it. I needed to take a peek inside to see what the tenant had in there and then meet with a Realtor to get it listed. I also wanted to see the lake again. Over the past eight years — since buying my R44, in fact, I’d flown at least 200 hours at the lake, covering its length from the Dam to Hite at least a dozen times and even going as far as Canyonlands National Park two or three times. I’d worked with a video crew to make an aerial tour of the lake and was ripped off by the filmmaker, who disappeared with $26K of my money, leaving me with a hard disk of mediocre raw video and a hard lesson learned. (And no, I’m not interested in discussing this.) There’s no arguing that Lake Powell is one of the most beautiful places in the Southwest and the best way to appreciate that beauty is from the air.

But, at the same time, I was leery of winter photo shoots. Back in February 2011, I’d gone to Bryce Canyon for a 360° Panoramic photo shoot with this same client. A snow storm and cold weather had delayed our flight and made it damn near impossible to get the helicopter started when we were ready for the shoot. It required a gas-heater and generator under the helicopter’s engine compartment to warm the engine enough to crank it. The delay meant we couldn’t get out at first light as originally intended. When I checked the weather and saw freezing temperatures forecasted for dawn and dusk at Lake Powell, I remembered the Bryce Canyon problems and began worrying about a replay. Although my helicopter has a primer, no amount of priming will start that engine if it’s too cold. I also remembered another January photo gig up there and how cold it had been in flight. Those guys had kept me flying for about 3 hours — I even had to land for fuel at Cal Black Memorial halfway up the lake from Page. It was so cold that the back seat photographer had given up shooting and was leaning away from his open door as far as he could in an effort to keep warm. I never did like cold weather.

All of these thoughts were going through my head when I contemplated the job. But a revenue flight is a revenue flight and I had the possibility of being paid for 10 hours or more of flight time over four days at one of my favorite destinations. After losing at least $10K of revenue in Washington due to my early return, my inability to concentrate enough for writing jobs, and the huge sums of money I was paying my legal team to help me protect my business assets from the greedy, cheating liar I’d married six years before, I could really use the cash. So I convinced myself that I was glad about the work and prepped to make the trip.

Getting There

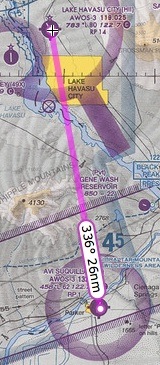

We flew up there around midday on New Year’s Day. The conditions were remarkably good. I’d flown through unforecasted low visibility and snowstorms on my way from Wickenburg to Winslow the day before, but there was none of that on Tuesday. The flight went well and I got a chance to show my companion even more of Arizona’s remote scenery from the air. This post with video gives you an idea of what we saw, although we weren’t flying from Phoenix so the actual route and views differ. (We got to see Sedona on our flight the day before.)

After a brief tour of Horseshoe Bend, the Glen Canyon Dam, and Wahweap Marina for my friend, we touched down at Page Municipal Airport. The folks from American Aviation were out to the helicopter with a van before my blades had even stopped spinning.

Penny lounges in the sun under the desk in our hotel room.

Penny lounges in the sun under the desk in our hotel room.

We grabbed the rental car I’d arranged for, stopped at Stromboli’s restaurant for a huge calzone to share, and checked into the Days Inn hotel. The pet-friendly room was clean and well appointed with a king-sized bed, refrigerator, desk, free (and fast) wifi, and a sliding door that made it easy to take Penny outside. Best of all, it was on the south (sunny) side of the hotel, so the afternoon sunlight streamed in through the window, giving Penny that patch of sunlight she always seems to enjoy.

First Flight

A while later, I was back at the airport. I had to prep the helicopter for the afternoon flight. That meant removing the two passenger side doors, adding a quart of oil, and laying out the life jackets. I make all my passengers wear flotation devices during photo flights over the lake. In more than a few places I fly there, an engine failure means a swim. I didn’t want anyone drowning because they couldn’t find or put on their life jacket.

Back in the terminal, Mike arrived with his group. He took one look at me and said he was seeing only 2/3 of me. I told him I’d lost only 20% of my body weight, not a third. I had already told him in email that the reason I had to lose weight was because he kept gaining it.

I gave his group a safety briefing. After each topic, Mike translated what I’d said into Russian. About half the group spoke some English and about half of those spoke it well.

I took the first group out to the helicopter: two photographers and a passenger. Normally, I won’t do a photo flight with three passengers on board, but the helicopter performs magnificently in cold weather, so it wasn’t an issue — even with nearly full tanks of fuel. They all climbed on board and I made sure they were strapped in. Then I started up the engine, warmed up, checked their seat belts one more time, and took off.

Mike’s instructions had been specific: start with Horseshoe Bend, which is near the airport. Then head uplake to Reflection Canyon, the San Juan Confluence, and an odd canyon I call “Canyon X” because of the way it looks from the air. Then back down lake to Padre Bay and Alstrom Point for a look at Gunsite Butte. So that’s what I did.

Oddly, when I first took off, I felt a bit hazy about the locations of all these points. It wasn’t until we were heading uplake, past Tower Butte that it all started coming back to me. Mostly it was the reporting points the tour pilots used. I’d learned these points so I understood where they were when they made their calls. I also used them so I could tell them where I was. Tower Butte, Padre Butte, Gregory Butte, Rock Creek, Dangling Rope, Rainbow Canyon. That’s as far as most of the tour planes went. I went a little farther, to the confluence.

At 3:56 PM, we were just passing the north end of Boundary Butte, heading uplake.

I flew uplake at about 5500 feet staying mostly over the river channel. The air was mostly calm and the water was glassy smooth in more than a few places, creating amazing reflections of the red sandstone cliffs. Just past Gregory Butte, the wind picked up a bit, ruining any chance of reflections on the lake surface.

I reached Reflection Canyon — poorly named, in my opinion, because I’ve overflown it at least 100 times and have seldom seen any reflections there — at 5500 feet. I began a slow climb as I flew a racetrack pattern around the canyon, spiraling up in altitude. Our next destination was the twisting course of the San Juan River near its confluence with the Colorado and that was best viewed from 7000 feet or higher. When my photographers were finished with Reflection, I moved on to the San Juan and began circling it, spiraling up to 8500 feet as I circled it twice. Off in the distance, I could see the buttes in Monument Valley.

It was cold. The outside air temperature (OAT) gauge said -9. That’s -9°C, of course, or 15°F. I was wearing a pair of jeans and a long sleeved shirt under my leather jacket. I had a scarf and thin wool gloves on. Every part of me was cold. I hunched over the controls, trying to use my body to keep my body warm. I wasn’t succeeding. At times, my teeth chattered.

After the San Juan, I took them around Canyon X. Then we headed back toward Padre Butte. I was flying almost directly into the sun. I had a baseball cap on to offer some protection from the sun’s glare, but it didn’t help much. I kept at 6000 feet so I wouldn’t have to worry about flying into any buttes or canyon walls along the way.

The east side of Padre Bay, shot from my helicopter’s nose cam from the south.

My passengers wanted to see the northeast side of Padre Bay, so we flew there first. I took them past Cookie Jar and the pockmarked rocks around it. There were some nice views of the canyon walls on the east side; my nose cam even got a nice shot. By the time we got to Gunsite, the sun was very low and the light had faded. The view wasn’t much to get excited about. My passengers had enough and we headed back.

We touched down at 5:20. The fuel truck was waiting.

Thawing Out

I was frozen solid. Or at least I felt as if I was. My right hand, which had been clutching the cyclic in a death grip, was probably the worst. I was shivering almost uncontrollably. I threw the doors back on the helicopter, locked it up, and headed back to the hotel.

It took me nearly an hour to warm back up.

Mexican dinner with 11 Russians.

We went out to dinner at a Mexican place. If you ever want a weird experience, watch 11 Russians try to order Mexican food in English from a Mexican waiter. Dinner was good, but the portions were too large. Seriously: who needs that much food in a tourist town when you can’t even bring leftovers home? The bowls of soup looked as if they held a half gallon of the stuff.

Afterward, I went to Walmart to see if I could buy a pair of long johns and a turtleneck. I found a pair of leggings — the only pair in my size was brown. (Walmart offered all kinds of color options in sizes 2X and 3X.) I bought a few turtleneck shirts for the next few days.

Dawn Flight

The next morning, I layered my clothes: leggings under jeans and turtleneck under sweater under jacket. That should keep me warm, I reasoned.

I was out at the helicopter by about 6:45 AM. It was still dark, although I could see the sky brightening beyond the Navajo Generating Station. I took the doors back off and did a preflight with a flashlight. The quart of oil I’d brought into my hotel room overnight poured easily. I hooked up my GoPro with my skid mount so it would point the same general direction my passengers would be shooting. I drove the car back to the terminal building and parked it out back.

My passengers knew how to dress for freezing weather.

I greeted my passengers when they arrived at 7:20, got their life jackets on, and buckled them in. There were just two men. I realized that they were wearing ski clothes. They were Russians, accustomed to cold weather. And they were wearing ski clothes. You think that would have told me something.

I primed the engine a good ten seconds, pushed the starter button, and was surprised that the engine caught almost immediately. I fed it a little more fuel as I flicked the strobe, clutch, and alternator switches on. It sounded rough at first, but soon smoothed out. When the clutch light went out, I brought the RPM up to 68% and began the long wait for the engine to warm up.

While I waited, I used my laminated startup check list to scrape the frost off the cockpit bubble. I suspected that even in full sunlight, at 17°F and 90 knots for a wind chill factor of -14°F, it was unlikely to melt off.

When I was ready to go, I made my radio call and started pulling up on the collective to pick up. Immediately noticed that the collective was heavy. When I got it into a hover, I realized that the cyclic was extremely stiff. Almost — but not quite — as if they hydraulics weren’t working. I checked the switch; it was in the correct position. Circuit breaker was fine, too. I hovered a tiny bit hack and forth over the helipad. Stiff but not too stiff to fly. I assumed the hydraulic fluid was cold and that the situation would improve as it warmed.

Padre Bay, by the dawn’s early light.

We took off just as dawn was breaking behind the power plant. We headed uplake at 5000 feet. As I flew, I admired the way the early morning light seemed to kiss the tops of the buttes and cliff faces.

Of course it was another perfectly clear morning. Some people might think that’s nice, but for photography, it sucks. The light gets harsh quickly and, without clouds and shadows, there’s little depth to the scenery. Besides all that, a clear blue sky is downright boring. But that’s part of life when doing photography in the desert southwest.

So we were racing uplake to the three target areas, hoping to get there and back to Padre Bay before the light got too bright.

Gregory Butte at first light with a view up Last Chance Bay.

It was another beautiful flight — and I can prove that with hundreds of photos. Honestly, I’ve seen so much of Lake Powell from the air during the “golden hours” that none of the photos really impress me anymore. It has to be one of the most beautiful places on earth and there’s no better view than from a helicopter at dawn.

My passengers wanted me flying higher, so I climbed to 6000 feet. I was freezing cold again before we got to the San Juan Confluence. I started doubting the wisdom of doing these flights. And started wondering how many layers of clothes I needed to wear to keep warm. My hand on the cyclic seemed frozen solid. And my feet were freezing, too. But I kept flying, knowing that when the light got too harsh, we’d be done.

I circled each target area two to three times as instructed. My photographers snapped dozens of photos. I’d glance at them occasionally and see them moving their cameras in every direction, framing up their shots. Occasionally, the one who spoke English — and he spoke it very well — would give me instructions. But in general, they let me do what I liked.

When they were finished with the uplake target areas, we headed back down the lake. Along the way, they stopped me to photograph several other places where the light was hitting just right. All I could think about was how cold I was and how much I wanted to be on the ground.

Horseshoe Bend from the south. The narrow canyon is usually full of deep shadows.

We finished up with Horseshoe Bend, which is best photographed when the sun is high. News flash: the winter sun is never quite high enough to photograph Horseshoe Bend without deep shadows.

Warming Up Again

We were on the ground by 9:20 AM. Shutdown went quickly; the engine had cooled considerably on my approach. I felt frozen and was shivering badly when the fuel truck pulled up to fuel us. My feet felt like stumps as I joined my passengers for the walk back to the terminal.

I left the doors off the helicopter and drove back to the hotel, stopping at McDonalds for a quick bite to eat and a more important glass of orange juice. I was shivering the whole time. In fact, it took me a full hour and a half to stop shivering. Then I stretched out on the bed and fell asleep. I didn’t wake up until after 1 PM. That had me really worried — I never sleep like that in the middle of the day. I was certain I was coming down with a cold.

With at least two flights left to do, I needed warmer clothes.

My “armour” against the cold.

I headed out to a sporting goods store I found near Safeway. The saleswoman there set me up with some Under Armour. I didn’t care what it cost. I bought a shirt, a pair of pants, and a pair of gloves and left $180 with her. Then I headed back to Walmart and found a pair of thermal socks in the sporting goods department.

We hit Sonic for lunch and had another big glass of orange juice. We had a nice little walk with Penny while we waited for the food.

Then I went back to my room to dress all over again. Three layers of shirts under my leather jacket, 2 layers of pants, the thermal socks. I’d put the new gloves on before taking off.

I made it back to the airport by 3 PM, in time to prep for my afternoon flight.

Third Flight

My passengers were late and slow about getting on board. As a result, we didn’t take off until after 4 PM. This turned out to be very unfortunate for them.

Navajo Canyon, from the south. Although the canyon walls are not very high here (compared to Horseshoe, anyway), there were already deep shadows.

Like the previous afternoon’s flight, these folks wanted to start with Horseshoe Bend. I thought it was a waste of time, but doubted whether they’d believe me so I kept quiet. We circled Horseshoe Bend twice, then headed uplake. Along the way, they caught sight of the pair of islands in the middle of Navajo Canyon and instructed me to circle them. I did that twice. It wasn’t until 4:28 that we continued heading uplake.

I was cold. Still. I realized that the gloves I’d spent $25 on weren’t much better than the junky gloves I’d worn on the previous two flights. I tried to put another glove over the one on my right hand, but couldn’t manage it while holding the cyclic. I was able to jam my left hand under my leg or between my legs to keep it warm. Occasionally, I’d wrap my left hand around my right hand on the cyclic in an attempt to warm my right hand. I don’t think it worked. My body was warm enough but my legs were not. My feet were nice and toasty — at least my $6 Walmart socks were doing their job. Overall, however, I was definitely warmer than I had been on the previous two flights.

Canyon X and Reflection Canyon were already in deep shadows when we got there 15 minutes later. Even the twisting course of the San Juan River was in shadow — although there were some decent reflections there. I circled and climbed and circled and descended. When I got the word, I headed back down lake.

By this time, it was after 5 PM. Sunset was 5:20. It would take at least 15 minutes to get all the way down to Padre Bay, the next target location. But I’d noticed on the previous day’s flight that the sunlight was already too soft to really show off the red rock glow by 5:10. My passengers were running out of light and there was nothing I could do.

The cliff faces across from the mouth of Rock Creek were nicely illuminated in the last light of the day.

Of course, since we were flying into the sun, my passengers could see it just as well as I could. I think they realized that we wouldn’t reach Padre Bay in time. So they had me circle a few areas that were still illuminated, like the cliffs across from the mouth of Rock Creek.

“Very dramatic,” my front seat passenger said. I couldn’t argue.

By the time we reached West Canyon, only the highest points — like Navajo Mountain — were still in sunlight.

After that, we tried to check out the area south of West Canyon. This area is normally outrageously beautiful in last light, but often overlooked by photographers who concentrate on the cliffs and buttes around the lake. But by that time, only the highest points still had light on them. I watched the sun’s orange globe sink below the horizon in the west.

“Go back?” I asked my clients?

“What is our choice?” the English speaker replied glumly.

I didn’t tell them that another photographer had once kept me out nearly an hour past sunset at the lake — so late that I needed my landing light to find the helipad. Instead, I just headed back.

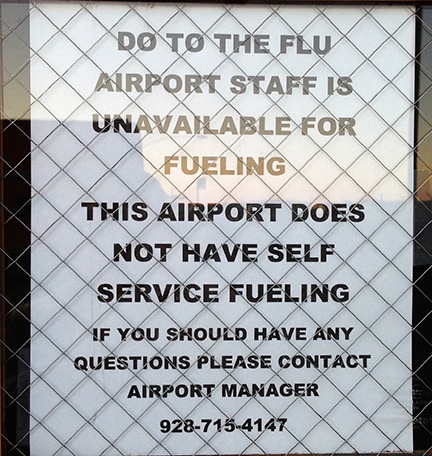

Back on the ground, I walked them to the terminal. It was locked. The fuel guy was gone and my doors were inside the building. I helped them get through the gate, then drove around to the front of the building. A few people were still inside, so I was able to retrieve my doors. But no chance of getting fuel. Unless I was willing to pay a $50 after-hours callout fee — which I was not — the next morning’s flight might be a lot shorter than desired.

Talking My Client Out of Flying

I buttoned up the helicopter, grabbed a quart of oil to heat in my room overnight, and went back to the hotel.

I was cold and I didn’t want to fly any more than I had to. I was worried about getting sick.

I called Mike and told him about the fuel situation. I told him I thought we had enough for about an hour and a half in the morning. Then I talked to him about the second part of our photo gig: the Goosenecks of the San Juan, which is near Mexican Hat, UT. I had two logistical problems.

First, I didn’t have a landing zone less than 15 minutes flight time from Goosenecks. The only good landing zone was at Goulding’s Lodge, a private runway. That means that each flight would likely take 45 minutes to an hour.

Second, the closest fuel was at Cal Black Memorial Airport on Lake Powell, about 20 minutes flight time from Gouldings or Goosenecks. That meant a 40-minute refueling run.

Mike, of course, had to pay for all of my flight time. He could do the math as well as I could. It would likely add 4 to 5 hours of flight time if he decided to move forward on the Goosenecks flights. He said he’d talk to the photographers and see what they wanted to do. We hung up and I crossed my frozen fingers that they’d pass.

Fourth Flight

I was back at the airport at 7 AM the next morning, prepping for my flight. Since the fuelers for Classic Aviation were already there, I ordered fuel from them, topping off the tanks.

Frost on the bubble.

I repeated the previous morning’s routine, although I did scrape the frost off the bubble before my passengers arrived. There was a lot more of it. Later, when I returned, I’d still see tiny piles of the stuff on my helipad, where it had stuck to the ground but failed to melt.

I had three passengers: two photographers and an observer. They were all women.

I lifted off at 7:50 AM, 11 minutes after sunrise. The controls were so stiff that I was almost certain the hydraulics had failed. I set it back down, tested the controls, and realized that it was just the cold again. Worse than the day before. I decided to give it a go; I could always turn around and come back. Fortunately it was operating normally within 5 minutes.

An early morning view of what I call Canyon X, from the air.

An aerial view of the San Juan River near its confluence with the Colorado at Lake Powell.

Reflection Canyon from the air.

In my opinion, this flight had the best light along the way. The sun was high enough to illuminate the rock faces, but low enough to cast shadows that added depth to the scenery. And the light was soft and red — just perfect (in my opinion) for photographing the lake. Indeed, my uplake skidcam images are better from this fight than any other.

And because we’d gotten a later start than the previous morning, there was also better light on our target areas. Canyon X, for example, had lots of interesting light and shadows. The twisting course of the San Juan River seemed to glow in the morning light. Even Reflection Canyon was more interesting than in previous flights. There were even some reflections down there.

Because we weren’t racing to beat the sunset, the flight was more relaxed, too. Sure, the light wouldn’t be as “good” later on in the flight, but it wasn’t as if we’d run out of light. So we took our time and circled each point as many times as necessary. Stress free.

I was still cold, of course. I’d layered up a little better and was wearing two pairs of gloves. My hands and legs were still cold. I was not looking forward to the prospect of more flights that afternoon out near Monument Valley.

After finishing up near the Confluence, we headed back toward Padre Bay. We did a few circles in the area. The light was nice, but the golden hour was nearly over. They wisely decided to skip Horseshoe Bend.

We were on the ground by 9 AM. I didn’t hang around. I got into the rental car and headed back to the hotel to pack.

Finishing Up and Heading Out

Mike called when I was halfway finished packing and sucking down yet another orange juice. He came by the hotel to pay for the flights. Fortunately, he’d decided to skip the Goosenecks flights. I was relieved. I’d pretty much decided to say no and was wondering how I’d tell him. Now I didn’t have to.

Mike paid for the flight time and we said our goodbyes with a hug. It would likely be the last time we worked together. I was moving to Washington State and, unless he wanted aerial tours of the Palouse (another one of his destinations), he’d have no need for a helicopter in my area. I was sad to see him go.

Later, I met with a Realtor at the hangar I need to sell. We discussed terms and I was not happy to learn that an agreement with them would require me to pay them a commission even if I sold the hangar on my own. I still don’t get the logic in that.

We were loaded up — with the doors on! — and ready to depart by 12:45. I was really looking forward to getting home.

The Little Colorado River Gorge from about 200 feet above the rim.

The flight back was uneventful. I did a straight line to the Little Colorado River Gorge, which I flew over rather low to get a dramatic shot with the skidcam. Then I straight-lined it to my Howard Mesa property, which I always fly over when I’m in the area. From there, a straight line to the west side of Granite Mountain near Prescott and then a straight line to Wickenburg Municipal.

As I was coming in, a friend of mine from my Papillon days back in 2004 was leaving on a Game and Fish survey job. We spoke briefly on the radio; he’d join us for dinner later that evening.

I was glad to get the helicopter tucked away into the hangar and even gladder to be in my truck heading home. I was looking forward to at least a few days without travel — and even longer without freezing cold.

Penny lounges in the sun under the desk in our hotel room.

Penny lounges in the sun under the desk in our hotel room.