I compare art show venues to see which ones really do give me the best bang for the buck.

I’ve got a sort of running debate with a friend of mine about art show fees and which methodologies are best for artists.

Fee Considerations

Clearly, in a beautiful, perfect, artist-friendly world, show fees would be low and shows would be full of art lovers with deep pockets and plenty of empty wall space or jewelry/pottery/other craft needs.

But that’s not the way it is. Show runners want to make money far beyond the cost of running their venue and the artists are the draw. They set their fees based on what they think artists can afford to pay, with the goal of filling every available spot.

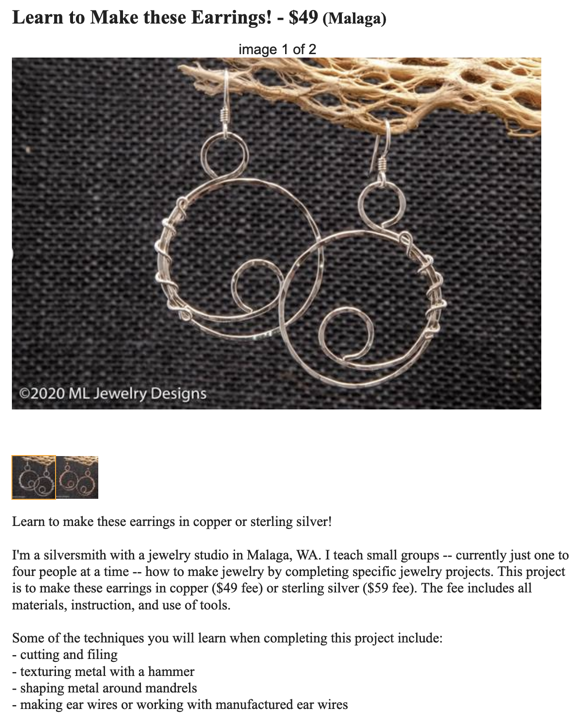

Here’s my jewelry sales booth as it appeared at Leavenworth Village Art in the Park on May 19. I’m trying to display my work as serious and elegant; most folks seem to think I’ve done it.

Artists, on the other side of the transaction, have to consider fees when they decide which shows to apply for. The higher the fees, the more work needs to be sold. Is it possible to sell enough work at the artist’s price points to cover show fees? And what about other expenses, such as the cost of getting to and from a show, lodging, parking, and who knows what else?

In general, better shows — ones with good track records for attracting lots of shoppers and scoring high on artist satisfaction — command higher fees. That can also be said for shows that can attract shoppers with deeper pockets or ones where the quality level of the artist work meets a higher than average standard. In both cases, the potential to sell work at higher prices might make it easier to cover fees.

But in nearly all cases, it’s a gamble. And in the short time I’ve been doing art shows, I’ve seen that firsthand.

Two Fee Methodologies

There are several fees involved with doing art shows and it’s worthwhile to take a look at each one.

- Application Fee. This is usually a small amount of money — under $50 but usually closer to $10 or $20 — that must accompany an artist’s application to participate in a show. It is non-refundable and is apparently used to cover administrative costs.

- Jury Fee. This is also usually a small amount of money — again, under $50 — that’s paid to judge an artist’s work before acceptance. Artists are normally required to submit photos of their work and their booth and may also sometimes be required to submit one or more photos showing them actually making the work to prove that they make it themselves. This is also non-refundable. Some shows will charge just a jury fee, if the show is juried, and not an additional application fee.

- Booth Fee. The booth fee is usually the expensive part of doing a show. Fees can range from $20 for a Farmer’s Market table to well over $1000 for a spot in an indoor venue showcasing fine art in a major city. Just about every show is going to charge a fee for your space, based in part on the size of the booth and its position. A 10×20 foot space that’s open on two or more sides — like in a corner — would usually cost significantly more than a 10×10 space in line with other artists.

- Commission Percentage. In addition to the booth fee, some venues charge a commission based on artist sales. They could process the sales of all artists centrally or provide special sales slips for artists to fill out to record each sale or use the honor system for artists to report sales. Commission percentages vary and are usually higher at venues with lower booth fees.

- Other Fees. In addition to all this, some venues charge extra for power, draperies, tables, lighting, local business licenses, and insurance.

I’ll give you two examples.

Wenatchee Apple Blossom Festival Arts and Crafts Show, a three-day show where I’ve sold my work twice in the past four years, has the following fees:

- Application/Jury Fee: $30

- Local Temporary Business License: $25

- Insurance Fee*: $85

- Booth Fee: $299

Leavenworth Village Art in the Park, a three- to four-day show where I sell my work on about five weekends per year in the spring and late summer, has the following fees:

- One-time application/jury fee for season: $15

- Per weekend Security Fee: $30

- Booth Fee: $0

- Commission Percentage: 21%

—

* You can usually skip the insurance fee charged at an event by carrying your own insurance, which I do. It costs $375/year and covers all of my events.

The Debate

So the main part of the debate is this: which fee structure is best for artists? Flat fees or commission based fees?

First I need to mention one other thing: I’ve seen shows that have a relatively high booth fee — maybe $500 — plus a commission percentage of 20% or more. (I’m looking at you, Sacramento.) I avoid shows like that because I honestly don’t see how I can make any money. I also think those show runners are being unreasonably greedy and I don’t want to support them in any way.

Oh, this Seattle show! Although I paid the same as the artists in the main room with 10×10 booths, I was given a 10×7 space in a side room with six other unfortunate artists. The window behind my booth was old and drafty; on those November days, it was about 50°F in my chair. I didn’t lose money on this show, but sales were disappointing. I think I would have kicked butt in the other room, but who knows?

That said, the answer to the question of which is better really depends on the show. If it’s a great show and you have lots of sales, it’s better to avoid paying a commission on sales. After all, the more you sell, the more you pay.

But, at the same time, if the show is crappy and sales are low, commission based fees are better because you’ll pay less.

Let’s look at some hypothetical numbers, comparing the Apple Blossom show to the Leavenworth show. For the sake of argument, we’ll say the artist does Leavenworth just once so that one-time application fee doesn’t need to be split among multiple shows.

| Item | Apple Blossom | Leavenworth |

|---|---|---|

| Gross Sales | $3,000 | $3,000 |

| Fees: | ||

| Application Fee | $30 | $15 |

| Business License Fee | 25 | 0 |

| Insurance Fee | 85 | 0 |

| Security Fee | 0 | 30 |

| Booth Fee | 299 | 0 |

| Commission | 0 | 630 |

| Total Fees | $439 | $675 |

| Net Sales* | $2,561 | $2,325 |

| Sales Cost Percent (Net÷Gross) | 14.6% | 22.5% |

So in this case, the fixed fee event would be a better deal for the artist, allowing her to take home more money.

But what if the outdoor event was on a really crappy weather weekend? Cold and rainy and folks just didn’t want to come out? Say the artist sales that weekend were a disappointing $1,000. The story changes quite dramatically:

| Item | Apple Blossom | Leavenworth |

|---|---|---|

| Gross Sales | $1,000 | $1,000 |

| Fees: | ||

| Application Fee | $30 | $15 |

| Business License Fee | 25 | 0 |

| Insurance Fee | 85 | 0 |

| Security Fee | 0 | 30 |

| Booth Fee | 299 | 0 |

| Commission | 0 | 210 |

| Total Fees | $439 | $255 |

| Net Sales* | $561 | $745 |

| Sales Cost Percent (Net÷Gross) | 43.9% | 25.5% |

Totally different picture, no? Basically, the worse the show is for you, the less you pay in fees if your main fee is based on a commission.

This really comes into play when you have a totally crappy show, like the one I did in Spokane last November. Billed as a Holiday Arts and Crafts show where the show runners actually charged shoppers a fee to get in, most shoppers seemed more interested in buying $13 caramel apples than any sort of quality artist work. Between the show fees of $340 and the cost of making the 3-hour trip (each way) to Spokane, I wound up losing money on the show. (It would have been worse if I’d had to stay in a hotel, but I stayed in my truck camper on the fairgrounds and no one ever collected a fee.) Needless to say, I won’t be doing that show again.

But then again, if you have a great show that charges a commission percentage, it really costs you.

And that’s where the debate stands.

—

*Net Sales does not include other expenses of attending a show, such as transportation, lodging, parking, credit card fees, etc. All those do need to be calculated by the artist to come up with a total cost for the show when evaluating it.

What’s the answer?

Sunday mornings are always slow in Leavenworth, no matter how beautiful the weather is.

We don’t know how a show is going to be before we attend so it’s impossible to determine which will work out better in advance. Of course, prior attendance at a show can give you an idea of how it might work out. But even that isn’t guaranteed. I did well in Spokane in 2021 so I assumed I’d do just as well in 2022. I didn’t. Not even close. And the weather is always a factor, especially at outdoor shows.

I’ve done three shows in Leavenworth this spring and the first two were disappointing while the last one was really good. I paid relatively low fees for the first two but was hammered at the third. Still, my cost percentage remained between 22% and 26%. The percentage I take home is pretty solid. There’s some reassurance in that. It’s pretty much impossible to lose money at a percentage-based show. Low sales, low fees.

So there is no answer. It all depends.

And that’s part of what artists deal with when they try to sell their work at shows.

The other part? Setting up and tearing down a booth. Buying and maintaining display equipment. Getting to and from shows. Parking. Sitting in a booth all day, possibly leaving work unattended during trips to the restroom. Dealing with often thoughtless shoppers who make audible comments to friends about how easy it is to make this or how overpriced that is. Seeing your work handled by people who then drop it back down to bang against the metal display. Watching kids with ice cream on their hands touching everything. Keeping an eye out for dogs lifting their legs on table draperies and tent sides.

But let’s not forget the good stuff, too. Being told your work is beautiful. Being complemented on your unique designs. Having a customer buy an expensive piece that took you hours to make and telling you how much they love it.

All that should figure into the costs and benefits of being an artist at an art show, too, no?