An important part of crop protection.

The economy of this area of Washington State is based primarily on tree fruit production: apples, cherries, pears, and apricots. Indeed, Columbia River Valley around Wenatchee is one of the biggest apple producing regions in the world.

Fruit trees bloom in the spring, are pollinated by migratory bees, and form fruit. Throughout the summer, the fruit develops and grows. Months later, when the fruit ripens, it’s picked, sent to processing plants, and either shipped out immediately, as in the case of cherries, or stored for later shipment, as in the case of apples.

The timing of all this is determined by the weather and can fluctuate by several weeks every year. The trees get a cue from temperature to start budding and once the buds are formed, there isn’t much that can stop the seasonal progression.

Except frost.

Frost can kill flowers and developing fruit. A bad enough deep freeze over the winter months can even kill trees.

And that’s where frost protection comes in. Growers are deeply concerned about frost destroying a crop so they take steps to protect the crop from frost. In this area, they rely on wind machines to circulate the air in parts of an orchard prone to pockets of cold air.

This video shows wind machines in action at a pear orchard in Cashmere, which is near here. It looks to me as if the trees are in bloom. Unfortunately, the sound is turned off so you can’t get the full effect.

Wind machines look like large, two-bladed fans on a tall pole. Usually powered by propane, they’re often thermostatically controlled — in other words, they are set to turn on in the spring when the temperature drops down to a certain point. The blades spin like any other fan and the fan head rotates, sending wind 360° around the machine’s base.

The idea, of course, is that the cold air has settled down into pockets and that warmer air can be found around it and above it. By circulating the air, the warm air is brought around the trees and frost is prevented.

In California, they use helicopters to protect the almond crop from frost. (As a matter of fact, as I type this my helicopter is in California for a frost contract for the third year in a row.) The principle is the same, but the orchards tend to be much larger and I can only assume that it isn’t financially feasible to install and run wind machines in that area. (Hard to believe it’s cheaper to use helicopters, though.)

This year, some unseasonably warm weather has triggered a very early bloom. My clients tell me that their cherry crop is running 2 to 3 weeks early. Right now, cherries are in various stages of bloom throughout the area; apricots are pretty much done with their bloom. (Apples and pears will come next.) And since winter has not let go of its tenuous grip on us, the temperature has been dropping down into the low to mid 30s each night this week.

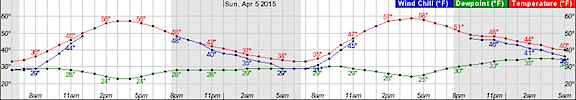

Well, not at night. It actually starts getting cold around 4 or 5 AM, as you can see in this weather graph:

The National Weather Service weather graph page for this area shows the forecasted highs and lows over time.

The result: the wind machines kick on automatically when it starts getting cold: around 4 or 5 AM.

Want to hear what a wind machine sounds like close up? This video has full sound as a field man starts and runs up a wind machine. He’s wearing ear protection for a reason. Stick with it to see the spinning head on top.

Wind machines are not quiet. In fact, from a distance, they sound exactly like helicopters. And as they spin, they sound like moving helicopters — so much so that when I first heard them in action back in Quincy in 2009 or 2010, I thought they were helicopters and actually got up to see what was going on. I suspect that to someone on the ground, they sound exactly like a helicopter drying cherries would sound.

Although there aren’t any orchards on my end of the road, my property does look out at quite a few orchards, some of which have wind machines. There are at least 5 within a mile of me — I can see 4 of them from my side deck. I can also see others much farther out into the distance. And when the close ones are running, I know it. It’s not loud enough to wake me up in my snugly insulated home, but it sure did wake me up when I was living in my thin-walled RV outside. And it’s definitely not something you can pretend you don’t hear.

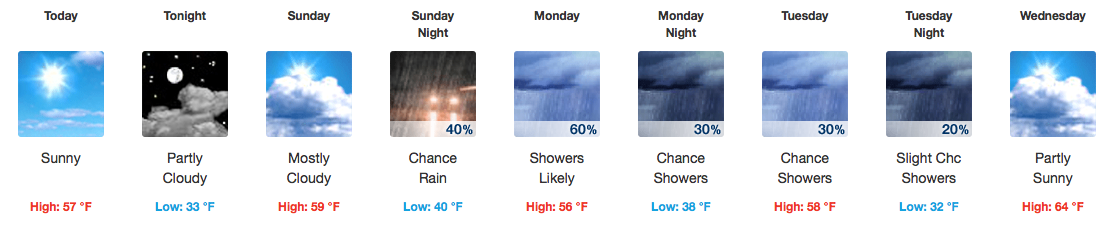

Fortunately, wind machines are a seasonal nuisance — much like other orchards noises: sprayers, tractors, helicopters, and pickers. Although frost season runs through May in this area, the machines only kick on during cold weather. Looking at the forecast, I can expect to hear them tomorrow morning and probably Wednesday morning, but not likely on Monday or Tuesday morning.

NWS Wenatchee forecast for this week.

NWS Wenatchee forecast for this week.

In the meantime, I’ve already gotten the heads up from my California client who might need me down there on Monday. After all, they don’t have wind machines.

For a helicopter pilot working in this area, wind machines are one of the obstacles that can be a hazard when drying cherries. They tower higher than the trees and their blades can be “parked” at any angle or direction. Although some growers will try to use wind machines to dry trees while waiting for pilots, my contract states I won’t fly in an orchard with wind machines spinning so they’re usually turned off when I arrive — or right afterwards. But if the blades aren’t parked, they can move. And one pilot I know learned the hard way about what happens when a helicopter’s main rotor blade hits a wind machine. (He’s okay; the helicopter is not.)

To sum up, wind machines are an important crop protection device that can be a bit of a nuisance with predawn operation in the spring. But I don’t mind listening to them. Like so many orchard owners in the area, my livelihood depends on a healthy cherry crop. If that means tolerating some noise 10-20 mornings out of the year, so be it.

A few weeks ago, I was contacted by Marvyn Robinson, a U.K. pilot and podcaster. He wanted to interview me for his podcast,

A few weeks ago, I was contacted by Marvyn Robinson, a U.K. pilot and podcaster. He wanted to interview me for his podcast,