Or why you shouldn’t lie to your pilot about your weight.

The other day, I booked a scenic flight for three passengers. At the time of the booking, I took the passenger names and weights — as I always do. Here’s what I was told:

Joe: 200 lbs

Bill: 200 lbs

Sally: 150 lbs

Why Pilots Ask for Weights

You might be wondering why a pilot needs the weight of passengers on a flight. After all, when you book a flight on United or US Airways, they don’t ask how much you weight. Why should a helicopter pilot care?

First of all, you should be aware that the airlines do care about weights. Weight information is required to calculate aircraft weight and balance (W&B) at takeoff and landing. The airlines are allowed, however, to use a blanket estimate for each person’s weight. This is set forth in an Advisory Circular issued by the FAA. (I found AC 120027C dated 1995, but I think this has been recently revised to account for heavier passengers; can’t find the new info, though.)

As a Part 135 operator of a small aircraft, I’m required to calculate an accurate weight and balance for each flight I conduct. The calculation is complex and customized to my aircraft. If I had to do it manually, it would take a good 15-20 minutes — with a calculator. Fortunately, I’ve created an Excel worksheet that does the number crunching and calculations for me, so the whole process, which I can do on my laptop, takes less than 5 minutes and spits out a required flight manifest and flight plan at the same time.

Weight and balance is important for safe flight. An aircraft is loaded out of CG (center of gravity) could fly erratically or have impaired controls. For example, if my helicopter is loaded too heavy up front, I might not be able to pull the cyclic back far enough to arrest forward movement in flight. That would make stopping and landing very difficult indeed.

Likewise, an aircraft loaded beyond maximum gross weight will not perform to specifications and could suffer structural damage. For example, if my helicopter is carrying a heavier load than what’s specified in my Pilot Operating Handbook (POH) and legally allowed, I might not be able to hover in ground effect or take off with a climb rate sufficient to avoid obstacles.

What a Weight and Balance Calculation Looks Like

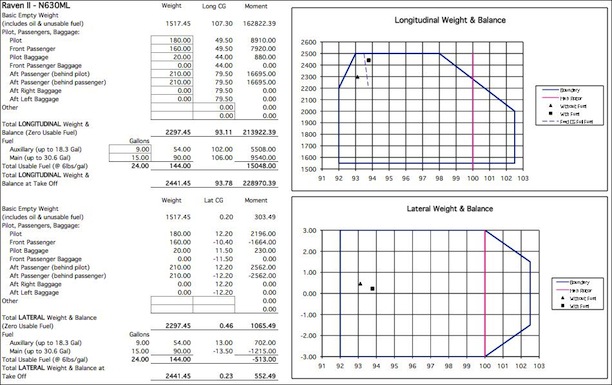

A weight and balance calculation includes a bunch of very large numbers that are subsequently divided to make much smaller numbers. The result is plotted on a graph surrounded by boundaries often called an envelope. The goal is for the plotted points and the line often drawn between them to be within the envelope.

Here’s what the W&B calculations and envelopes look like for the charter flight with Joe’s party with 1/2 tanks of fuel on board:

Note that the plotted square and triangle are within the envelope for both Longitudinal and Lateral Weight and Balance. I can look at these two graphs and see that based on how I’ve seated the passengers, we’ll be a little heavy in front and on the pilot’s side. But the weight distribution is within the range my aircraft and its controls can handle.

It’s Not a Time to Be Vain

Weight and age are the two things people are least likely to be truthful about. As a pilot, I don’t care how old you are — I’ve flown with passengers aged 6 months up to 95 years — but I do care how much you weigh. Lying is not in your best interest at all.

But because I assume people will lie, I automatically add 10 pounds to each passenger’s stated weight when calculating my W&B. So here’s the revised W&B looks like for Joe’s party:

Now we’re starting to get closer to the limits. The weight is way up front now — almost at my limit. Still okay to fly, still legal. But I know that there’s very little wiggle room.

I know from experience that I can make the situation better by putting a lighter person up front. So maybe I’d put Sally in the seat beside me. Here’s what that looks like:

That looks a lot better. See how the two boxes in the top graph have shifted to the right? That means the weight is shifted aft. More balanced.

But I also know from experience that some men are unlikely to take a back seat to their wives. And I know that big guys don’t fit very well in the back seat of my helicopter. There was a pretty good chance that the guy who’d booked the flight and was paying for it would not sit in the back.

Getting it Wrong Can Make it Dangerous

Unfortunately, not everyone underestimates weight by just a pound or two. Sometimes, they’re very wrong. Consider Joe’s party. Turns out that they’d underestimated weights by at about 20 pounds per person. Now my W&B calculation looks like this:

Ouch. As you can see here, the two plotted points on the top graph are just outside the envelope for forward CG. That means that the aircraft would be too nose-heavy for safe flight.

How could I fix the problem? Again, I could shuffle around the passengers, putting the lightest one up front. I could take the contents of the pilot’s baggage compartment and shift it to the baggage compartment for one of the back seats — or leave it behind. Loading less fuel would not help — although it would reduce the weight of the aircraft (and the endurance time), it wouldn’t resolve the CG issue.

How do I know all this? By playing what-if with my Excel spreadsheet and observing the results.

Don’t Lie to Your Pilot

What bothers me sometimes is the flippant attitude some passengers have about weight. These people were a good example. The man who booked the flight didn’t take any of it seriously. He just threw some numbers at me to answer my question. I could tell when I laid eyes on them that they were heavier than reported. One passenger confirmed his weight at 220; the other passenger’s wife confirmed his weight at 220. 20 pounds is not a small error. It’s 10%.

In this case, it was the difference between a safe flight and a potentially unsafe one.

What they don’t realize is that underestimating or just plain lying about weights can make a flight dangerous. They can put their lives at risk by providing incorrect information. Is it worth it? Just so a stranger thinks you weigh less than you really do?

I don’t think so.