I know how I like to work — and this wasn’t it.

Over the past eight or so months, I was a passenger on board a roller coaster that slugged its way through my life. The ride started quite suddenly in the summer when I realized that when I was finished working on the book I was revising (the software manual for QuickBooks Mac 2011, published in ebook format only), I had no other projects lined up. The publisher I like working with most had cut back on many titles that simply weren’t selling well enough to make them worthwhile and most of mine were affected. In fact, it became quite clear that I would not be revising my Excel book for the Office 2011 version of Excel. My Word titles were already dead and buried and much of the other software I’d written about in the past was either gone or not of any interest to anyone. As I wrapped up that QuickBooks project and finished off my summer as a cherry drying pilot, I began to worry about getting enough writing work to take me through the winter months.

A New Relationship with a New Publisher

A friend of mine mentioned in an e-mail to a bunch of writers that a publisher was looking for someone to do a book about Outlook 2011 for Mac. This was the replacement of Entourage, the Mac e-mail, calendar, and contact management component of Microsoft Office. I’d used Entourage in the past and liked certain aspects of it, including its ability to apply rules to outgoing e-mail messages and manage projects consisting of documents created with any program. I’d been thinking about switching back to Entourage to help me with my project management needs and this seemed like a good time to do it. I contacted the editor — who happened to be one of my very first editors with another publisher back in the early 1990s — and got more information. I drew up an outline and submitted it. He loved it. In fact, he loved it so much that he had me draw up another outline for another book, too.

I was very happy. It looked as if I’d be able to build a new relationship with a new (to me) publisher.

Things Begin to Sour

I got to work on the project in October with every intention of knocking it out before Christmas. At first, my editor seemed behind me on this strategy. But as I began submitting chapters into what appeared to be a void, I began to lose interest in the project. Looking back on it, I realize there were a few reasons for this:

- The void. I’d submit a chapter and not hear anything about it. I’d have to ask whether it was received to make sure it hadn’t actually gone into a real void. It didn’t seem as if anyone on the other end cared much about what I was doing. It wasn’t until weeks later that chapters started being tech reviewed and sent back to me.

- Lack of urgency. The original publication date had been set for sometime in the spring. I knew I could beat that and pushed hard to get the date moved up. This is the way I usually work. You see, a computer book has a limited shelf life. Every day it’s not on the shelf is a day sales are lost. This is the way I’ve come to think about all my books. Apparently, I was the only one who had any sense of urgency for the project and without the support of my publisher, I couldn’t maintain it.

- Book style. At first glance, the book was in a format I was used to: numbered step-by-step instructions. But rather than create sets of instructions for short tasks using generic material, the book would come with example files that readers could use to follow my steps to the letter using the same files I had. Not a big deal, but it did mean that I had to write exact instructions that would work for that specific example. What made the format difficult for me, however, was that before each long set of instructions, I had to write explanatory text that described all related features in full. The exercises had to illustrate these features in action. In my mind, I was writing the same thing twice. I struggled quite a bit with this because I couldn’t figure out where to put the screen shots without repeating them. This book (like most others) had a page count restraint. Screen shots take up a ton of space. I didn’t know if I was doing it “right” because I wasn’t getting any feedback from the publisher.

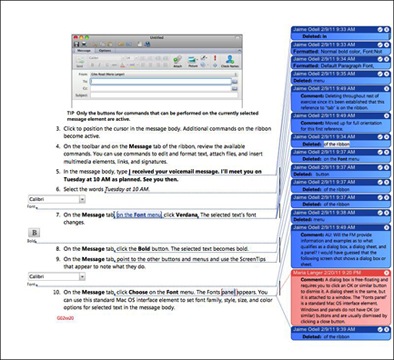

This is a screenshot of a typical page from the book during the editing process. I don’t know about you, but looking at stuff like this makes my eyes glaze over.

Manuscript template. This book was written and edited in Microsoft Word. I like Word — really. I’ve been using it since 1990 and it is a vital component of my writing toolbox. I’ve tried other word processors — Apple’s Pages and numerous other applications that might not even exist anymore. Word’s my choice. So that’s not a problem. What was a problem was the template, which included dozens of predefined styles for book text and figures and sidebars and headings. The template came with two extremely long style guides that attempted to explain how to use the template. These documents overlapped and had some conflicting information. And despite the fact that there were two guides, some information was missing. So I struggled to understand how to format the manuscript properly. In the end, I think I got it mostly right, but every day I was faced with pages that looked like a mess of text and images. This only got worse during the editing process when various editors used the revision tracking feature and comments to mark up the manuscript so that it was barely readable. Although this is common at most publishers, I prefer laying out my books as I write them and being able to see finished pages as I work.

- Disappointment with the software. I hate to say it, but I liked Entourage a lot better than Outlook. I understand that Microsoft’s goal was to provide Mac users with the “enterprise tools” that their Windows co-workers already have, but in rewriting Entourage to make it Outlook, Microsoft removed some features that I really liked. Project management was one of them. In addition, Microsoft apparently thinks that all Outlook users will be connecting to a Microsoft Exchange server so it put many features that depend on that technology right in user’s faces. For example, if a contact is not on your Exchange server, several tabs of his contact record will display error messages. I still don’t believe most Outlook Mac users are using Exchange and can’t imagine why they designed the software to rely so heavily on Exchange features.

My loss of interest really bugged me. I’d never felt like this about a book and I didn’t think it was a good sign. Not only was I failing to show a satisfactory level of professionalism with a new publisher — thus making them think twice about wanting to work with me again — but the related guilt was making me miserable.

This wasn’t me; why was I being like this?

I wanted to be done with the project very badly, but, at the same time, I simply didn’t want to work on it.

Frustration Kicks In

Things took a turn for the worse when frustration began kicking in. That was caused by a combination of the above and a few more things:

- Microsoft Exchange. I don’t have it and, frankly, I don’t want it. I didn’t think I needed it. When I realized that I would need to show Exchange-related setup and features, I was unable to get an Exchange account through my publisher or Microsoft. I had to buy one from a third-party hosting service. Then I had to buy a second one to work with it so I had two accounts that could interact. Of course, neither of these accounts were full-featured, so I couldn’t show everything I needed to. This really bugged me; the way I saw it, I was not able to do my job right and the publisher didn’t seem to care. So I stopped worrying about it — until a new tech editor started pointing out all the Exchange-related content that was missing. I thought I’d signed up to write an Outlook book for Mac users. Apparently, the tech editor thought I was writing an Exchange book for Outlook users.

- Conflicting instructions. About halfway through the project, I was told to hold off because a service pack update would be released “soon.” A month later, I was asked why I wasn’t submitting chapters. I was waiting for an update that never came. An update that would likely change many of the screenshots — and this book had tons of them — in several chapters I’d already written. I did not look forward to making all the necessary changes.

- Editorial comments near the end of the project. I’d submitted more than 10 of 14 chapters by January or February and that’s when they decided to have someone other than a tech editor read them. And that’s when the errors I’d repeated throughout the book began to emerge. The worst was related to “fictitious names.” I was supposed to draw all example names in the book from a fictitious names list that I didn’t use. Example e-mail messages had to be drawn from a list of fictitious domain names. (I couldn’t even use hotmail.com, which is owned by Microsoft.) Example phone numbers had to be in the range 555-0100 through 555-0900 (or something like that). Example mailing addresses had to be on common street names, like Main Street, Elm Street, First Street, etc. This affected text examples and screenshots. I spent hours redoing screenshots and editing text. This annoyed the crap out of me; if they’d reviewed it months ago when I submitted it, I would have fixed the problem from the start and not have had so much work to do.

I should mention here that I don’t blame the publisher. I’m sure this is they way they always work. Evidently, other writers don’t have a problem with it. That might be because their experience with the publishing process — and what it could be — is different from mine. Or maybe they don’t care about the quality of their work or maximizing book sales or working efficiently. Maybe they just don’t think about it as much as I do.

My feelings of guilt turned to feelings of anger. I cannot begin to tell you how many times I nearly backed out of the book. As far as I was concerned, I’d already blown any chance of doing more work for this publisher. And even if they wanted to work with me again, I couldn’t bear the thought of working with them again. It pains me to say this, but it’s the truth.

Halfway through the project, I e-mailed my editor to tell him that if he was interested in that other book, he should find another author for it. If they wanted to use my outline, fine, but I would appreciate some credit in the acknowledgements. That e-mail took a huge weight off my mind.

Probably his, too.

Not the First Time

This isn’t the first time a project has completely turned me off. For years, I wrote and revised a book about a certain Windows application that I didn’t use. I was uniquely qualified to work on it because of my experience in finance and I had no trouble coming up with solid content. The finished book was something I was proud to put my name on — and that means a lot to me.

I had two problems with the book, though: (1) I didn’t like (and still don’t like) using or writing about Windows and (2) the publisher seemed to have a knack of hiring at least one person in the editing/production process each year who seemed determined to punish me for taking on the project. For the first few years, I fought editors tooth-and-nail to prevent them from changing my voice and changing the meaning of what I’d written. An editor one year would change a sentence to her way and the editor the next year would change it back to the way I’d originally written it. They were justifying their existence. And production people would cut illustrations that were referred to in the text without cutting the references or place illustrations in idiotic place. And, in later years, a handful of tech editors who were more concerned with me leaving out obscure tips and shortcut keys than providing helpful feedback about content.

Making matters worse was the book’s insane deadline — the whole book was written based on beta software every year and the final manuscript was due before the software was finalized. For about two months every summer I’d suffer through the process of getting this book done.

In the beginning, it was worth every headache. The first edition turned out to be the second bestselling book of all time (up to that point) for the publisher’s imprint. For the first few years, it sold well and I made good money. But who really needs annual updates to software and the book about it? Some years, there was very little new material to write about because the software simply wasn’t that different. Book sales started to droop and I began seeing less and less reward for my effort. One year, I turned the book down, but they got me to do it again by offering me a better advance. That lasted a few years. Then they cut the advance — after all, it wasn’t even selling enough copies to cover the advance anymore — and I backed out after a total of 11 or 12 editions. Someone else does it now and frankly, I’m glad.

Past Experiences have Ruined Me

And that brings me back to the point of this post. Not only did I want to get these experiences off my chest, but I want to explore why they were such bad experiences in the first place.

I think the main part of the problem is my past experiences. I’ve written or revised more than 70 books since 1992. The vast majority of these books are in Peachpit’s Visual QuickStart Guide (VQS) series. In fact, I’m willing to bet that I’ve authored more VQSes than any other author.

Although Peachpit (as a company) has changed dramatically since I began writing for them in 1995, they still seem to understand that a book is written by an author. Because of that, each book project centers around what the author does — at least in my experience. They don’t pull in a huge editorial staff with members that each have their own agenda to hack apart a manuscript and make sure the author knows she’s just a cog in a big corporate wheel. Hell, they hardly edit my work at all.

I created this the other day. Not only is this a lot easier on the eyes, but I’m rewarded with a sense of accomplishment every time I finish a page. That’s a real motivator for me.

Another thing I’ve grown accustomed to is laying out my own books. I do “packaging” for Peachpit — that means that I submit my manuscript as finished, laid out pages that I create in InDesign. I can visualize each page and how the information on it is presented because I create each page as I go. The result is a book that I feel good about because I’ve built every single page from the ground up. This is a feeling I simply can’t get when I work with Word template manuscripts covered with weird formatting, editing markup, and comments.

Also important is that sense of urgency: of needing the book done as soon as possible — or even sooner. Even my annual Windows book project had that feeling. My editor was always in the loop, encouraging submissions, providing feedback, answering questions, reminding me of the fast-approaching deadline. Sure, they’d hand me schedules for completion that I’d just ignore, but I always got it done on time because I was always encouraged to do so. I work best under stress — despite how damaging the health gurus say that is. It’s like I’m climbing up out of a gorge as floodwaters approach and I’m thrilled when I get to the rim safely with a new book in hand.

The point is, I’m used to working a certain way. When I’m forced to work a dramatically different way — one that is centered more around the publishing machine than the author or the book — I’m simply not happy. And yes, I do realize that we all do work we’re not happy doing. But I work better when I’m happy; I produce a better product and feel better about my career choices and life.

Bring on the Challenge, Bring on the Urgency

Fast forward to today. I’m working on a revision to one of my Visual QuickStart Guides. I don’t think I’m allowed to say what it is, but you can probably figure it out.

It’s a huge revision. I reworked the entire table of contents and shuffled content considerably while adding all kinds of new material.

On top of that, this book needs to be laid out in a brand new format I’d never even seen before. That means each page has to be reconstructed from scratch using a new template that I have to learn as I work. (Thankfully, the template came with one very thorough and easy to understand formatting guide.)

The software I’m writing about has also been completely reworked and I need to learn it as I write.

The book is over 600 pages long and I have less than two months to write it.

I’ve been putting in 8- to 12-hour days, 6 to 7 days a week. In the middle of each day, I’m convinced I’m not going to finish what I’ve set as a goal for the day. But at day’s end, when I’m done, I have a feeling of exhilaration that can’t be beat. I feel good about my work. I feel happy. I like this project.

This is how I like to work.

Learning from Mistakes

I’m sorry I took on the book from hell. I know better than to do that again. If my past experiences have ruined me for those kinds of projects, so be it. I’m too old and too set in my ways to compete with new authors who will deal with any nonsense handed out to them and consider themselves lucky to get it. I know better.

Print publishing — especially of computer books — is dying. I know that. It’s getting harder and harder to make a living writing content that readers think they can get for free on the Internet. There needs to be a new publishing market strategy and it’s sad to think that I might not be able to work with a publisher who understands that.

But part of the revolution in publishing is the rise of small presses and self-publishing. The way I see it, if I can’t get the projects I want with the publishers I want to work with, I’ll just have to come up with my own publishing projects. The next time I’m facing an empty project calendar, I’ll fill it with my own projects rather than take my chances with an unknown.

Lesson learned.

I was lucky. When I first got started as a writer, only the magazine publishers cared about word count. I’d spend a day writing a piece and then spend half the following day cutting it down to the necessary size. I still wound up submitting 10% to 20% more words than they wanted. The book publishers didn’t seem to care how many words I wrote.

I was lucky. When I first got started as a writer, only the magazine publishers cared about word count. I’d spend a day writing a piece and then spend half the following day cutting it down to the necessary size. I still wound up submitting 10% to 20% more words than they wanted. The book publishers didn’t seem to care how many words I wrote.