It was a mess. Now it’s not.

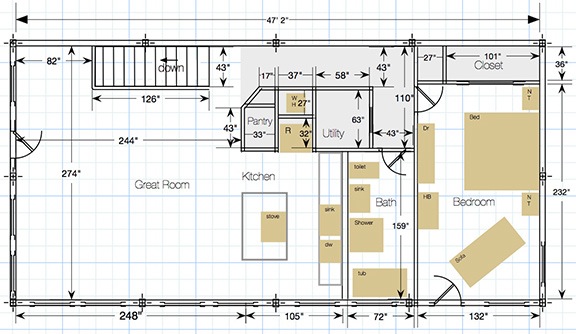

I need to start by reminding readers that I have a very large garage. The 60 x 48 footprint is split into a four car garage (24 x 48), a double-wide RV garage (24 x 48), and a shop/general storage area (12 x 48). If you’re doing math, that’s 2880 square feet.

Of garage.

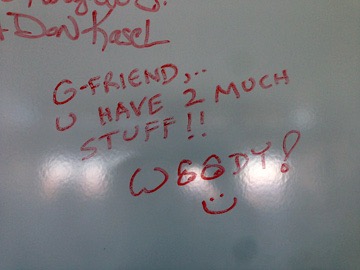

My friend Woody wrote this on my big white board during my moving party back in 2014. He wasn’t kidding.

The great thing about a big garage is that there’s plenty of space to store stuff. The bad thing about a big garage is that there’s plenty of space to store stuff.

I’m doing what I can to keep the garage organized, but even though most things have their place, that place isn’t exactly neat and orderly.

It Started with the Bungee Cords

The other day, I decided to clean up and sort out my bungee cords and ratchet tie downs — you wouldn’t believe how many I have because even I’m having trouble believing it.

I’d been racking my brains on a solution that would enable me to hang them neatly in order of size in a place that was out of the way. That’s when I remembered the curtain rods. When I lived in my Arizona house, I’d bought a few really nice ones. I wasn’t about to leave them behind — not even with shrimp stuffed in them (look it up) — so I packed them. Of course, I don’t have curtains on my windows here so I don’t need curtain rods. They remained wrapped up in bubble wrap in a corner of the garage.

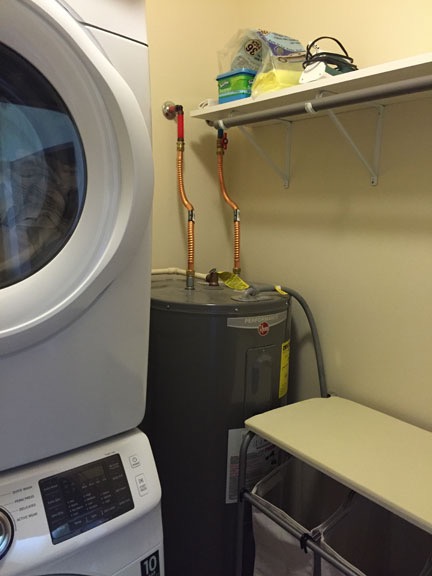

Some of my bungees and tie downs and ropes after putting up the curtain rod. I found a bunch more here, there, and everywhere the next day. The horizontal wooden beams are called girts, by the way. I live in a post & beam building. Beyond the vapor barrier is the metal exterior of my building. The car garage is not insulated.

I unwrapped the living room rod and grabbed a bungee cord. Sure enough, its hook fit neatly over the narrow black rod. A half hour later, the rod was hung on one of the girts in my Jeep garage — each garage bay is assigned a vehicle; the Jeep is in the first bay — and I was taking great joy in arranging my bungee cords and ratchet tie-downs. And ropes and straps.

The Shelves Came Next

I started thinking about how stupid it was to have all that dead space right below the bungee cords. How about a couple of shelves?

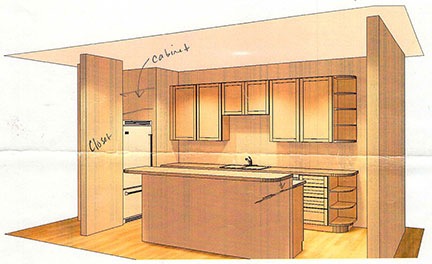

This was the first set of shelves I built for the garage. (Tiny dog for scale.) They’re free-standing and very heavy duty. And just plain heavy. I made two more shorter sets and a workbench with two shelves based on the same design. The RV garage/shop is insulated.

I should mention here that I’ve created shelves elsewhere in my garage. The biggest project was a set 8 feet long and 8 feet tall made of 5/8 plywood and 2 x4 lumber. It was quite a chore to build them, which I did with them lying down on the floor. When I tried to stand them up, I couldn’t. I had to wait for a friend to come by and lure him down into the garage — which was about as difficult as it sounds. (Men love my garage.)

I had limited space in the car garages, though. After all, I had to fit the cars in. Each garage bay is about 12 feet wide. There aren’t any walls between them — it’s one big open space. I knew I could fit shelves that were about 12 inches deep. (The big ones are 24 inches deep.) And I realized that I could build them in place, right against the wall, using the tops of the girts as supports for the shelves. That would save another inch and a half because each shelf could go right up against the exterior metal walls.

So I went to Home Depot and bought a sheet of about 1/2 inch plywood. While I was there, I saw a really nice piece of sanded 1/2 inch plywood that was in the cull pile because of a nasty scratch in one corner. But 70% off? A $35 sheet of wood for $10? No brainer! I brought both pieces over to the big wood cutter and got a Home Depot guy to cut each of them into 8 foot x 1 foot strips. Then I picked up a few 2x4s, along with some very nice 2×3 cull pieces and a long 2×4 cull piece. I don’t see anything wrong with using cull lumber to build shelves in a garage.

Did I mention that I also returned a bunch of lumber I’d bought about a year before but never used? The return completely covered the cost of the new lumber, as well as some additional screws and other supplies I needed in my shop. I threw everything into the back of the pickup, hung a red flag on the long 2×4, ran a few errands, and went home to make dinner with a friend.

The next morning, I really should have tended to my bees, but my truck was blocking my quad and I figured it would be best for me to offload the lumber and move the truck. Or maybe just offload the lumber and build the shelves to get the lumber completely out of the way.

So I did.

Let me explain a little bit about how a post and beam building — or pole building — is constructed. They start by digging holes in the ground and planting vertical posts. My building is made with a combination of 6×6 and 6×8 pressure treated posts. Then they nail the girts in horizontally, 24 inches on center. Next, they put the roof trusses atop the posts. They add rafters to finish framing out the roof. They cover that with insulation or a vapor barrier or both and then screw on the metal skin. They pour the concrete slab last — if the building has one (mine does). If you’re interested in seeing my building built in a time-lapse movie, be sure to check out this blog post.

The posts are usually 12 feet apart. In the bungee cord area, however, the distance between the door to my stairwell and the first post was only 7 feet. The reason: the front door and entrance vestibule is also on that wall. So the shelves needed to be just 7 feet long.

I dragged the saw horses my friend Bob had made me — they’re taller than standard sawhorses and much nicer to use — to the driveway outside the garage door, which I opened. I used my circular saw to make the cuts; later, I used my miter saw and table saw to get cleaner cuts when needed. And bit by bit I assembled the pieces I needed to build a short set of shelves with just a top and bottom shelf. The bottom shelf needed two cut outs — one for an electrical outlet (long story) and the other for the pipe for the outside hose bib. I got to use my new 1-1/2-inch hole saw, which I’d actually bought for a beehive project.

Here’s my bungee cord wall with the new shelves. I arranged all the tools I used for the project on the shelves.

I had to make a few blocks out of scrap wood to support various components of the shelves as I assembled them and screwed them together. I drilled pilot holes — I always do a neater job when there’s a hole predrilled for a screw. I used two 2×2 lengths that had been sitting around forever for the front horizontal shelf supports. These were small shelves so they didn’t need to be very heavy duty.

When I was done, I realized that I also needed a center vertical support. So I used a piece of scrap wood leftover from my windowsill project. Done.

And Then More Shelves

The truck wasn’t empty yet. I still had plenty of wood. I also had a really messy wall at the front of that garage bay. And time.

Here’s the old shelves with a bunch of car stuff on them. This whole area looks like crap here — and this was after I’d moved some trim wood stored there.

Here’s the old shelves with a bunch of car stuff on them. This whole area looks like crap here — and this was after I’d moved some trim wood stored there.

A long time ago, I’d bought a very heavy duty bookshelf for my books. I have a lot of books. I don’t remember if this shelf was from my New Jersey home or if I got it for the office I had at my condo in Wickenburg for a while. In any case, it eventually made its way to my Wickenburg hangar where I stored a lot of stuff on it. When I moved from Wickenburg to an East Wenatchee hangar and eventually to my new home in Malaga, the shelves came with me. I’d put them in the front of that garage bay and was using it to store miscellaneous auto-related stuff.

But it looked like crap.

I texted a friend of mine who has rental properties. Want an old bookshelf in decent condition? I sent a picture. Sure, she answered. Send a man with a truck, I told her. (She’d also taken my old Sony Trinitron off my hands.)

I took all the things off the shelves and used a hand truck to move the shelves over to a spot between Bay 2 (Honda S2000) and Bay 3 (Ford truck). Hopefully, the man with the truck will come within a few days. I swept. And then I got to work.

Four shelves, no shelf cutting needed because 8 feet was fine. I ripped two 2x4s on my table saw and used them for horizontal supports for the front of the shelves. Then I cut 2 2x4s to 79 inches and started piecing all of it together.

I had to crop the heck out of this cell phone photo. My truck mirror is on the right.

And that’s when Penny started barking like a little nut. I went out to investigate. She was halfway down the driveway at a standoff with a bighorn sheep. After some more barking, she spooked it and it bounded off. And then a dozen of its friends shot out of my side yard after it. There had been a whole herd of them less than 100 yards from where I was working and I didn’t even know it.

I took a break for lunch. I saw the sheep again later. They got very close. I got photos. But I’ll save that for another blog post.

I eventually got back to work. Again, I had to cut supports as I mounted each shelf. But once I got the hang of it, it went very quickly. I was done within an hour.

I put away my tools and set about organizing car and motorcycle-related stuff on the new shelves. I found a garage door opener for my old house. I found the stock mats that had come with my old Ford F350. (It had custom rubber mats so these were brand new; I photographed them and put them on Craig’s List.) I walked around my whole garage, looking for anything remotely car or motorcycle related and moved it to the shelves. I still had lots of space to fill.

I had some extra wall space between the shelves and the garage door. I measured a crate I had in my shop and moved it into position. I cut a piece of wood to give it a sold top. Then I moved my gas cans and spare propane bottle onto it. It made sense to keep stuff like that near the door where it could be quickly removed.

I found a few more bungee cords and put them away.

I spent some time admiring my handiwork. I might be the Queen of Clutter, but it isn’t by choice. If everything has a place, everything can be put away. The trick is finding a place for everything. Now I have a place for my car stuff.

These shelves look a lot nicer than the mess I had there before.

Up Next

Before I called it quits for the day and went upstairs to get cleaned up, I took a look at the wall in Bay 4. That’s where my little boat and motorcycle live. It’s a big mess and could really use some shelves. I’m thinking it might be a good place to organize all of my extra beekeeping equipment.

Looks like I’ll be hitting Home Depot for more lumber again.

Footnote

After writing this and posting it and then re-reading it online, I started thinking about all the work I’d done to build these shelves — and to do all the other things I’ve done as part of the construction of my home. A lot of it is difficult, challenging work that requires me to use my brains as well as my physical strength to get a project done. A lot of people would shy away from work like this and either hire someone else to do it or not do it at all. I know this from experience; so many projects at my Arizona house just didn’t get done. Or got done the way a contractor did them — which might not be the way it should have been done to meet needs.

Doing things like this myself is a task and a challenge I really look forward to. I don’t have a regular job that requires me to show up at an office or sit at a desk and make calls all day. My time is infinitely flexible. I could spend it sleeping all day or watching television or just goofing off. Yet many days, I choose to spend my time working hard on projects like this. The way I see it, there are four benefits:

- I get the thing done and get the benefits of that. In this case, I’ve got a bunch of neat, new storage spaces where I used to have a wall with a lot of stuff piled up on it.

- I save money on what it would have cost to hire someone to do the job. It’s a lot cheaper for me to spend a few hours on a project like this than to pay a carpenter to do it. It’s not like I don’t have the time.

- I learn new techniques, often through trial and error. The things I learn can be applied to other projects. The way I see it, if I can’t learn something every day, why bother getting out of bed?

- I get an amazing feeling of satisfaction every time I look at something I created with my own hands. My home is full of things like this. Read my construction posts to see what I’ve done; I’m proud of every single project I finished.

The people who think I’m doing these things because I’m cheap or bored are completely missing the point. They likely haven’t taken on projects like these, projects that can meet a specific need and give them so much satisfaction for every minute of effort put into them. It’s not difficult if you think it through and have the right materials and tools. Dare I say it? It’s fun.

Try it sometime and see for yourself.