And why other serious photographers should, too.

This photo of Bowman Lake at Glacier National Park appears in my photo gallery, Flying M Photos.

The watermark / copyright notice argument goes back and forth all the time.

On one side are the bloggers and readers of Web content who have created and seen more crap online than the rest of the human race combined. These people claim that copyright notices on photos are tacky and make the photos look ugly. They go on to say — and there is definitely some truth to this — that the average photo on the Web is so poor in quality that the photographer has no need to worry about it being stolen.

On the other side are the serious — or possibly professional — photographers who want to show off their work online but protect it from theft. These people are tired of seeing the results of their hard work and investment in costly equipment appearing on someone else’s Flickr account or in blog posts. Or, as in my case, in an e-mail postcard sent to me.

Why People Steal Photographs and other Web Content

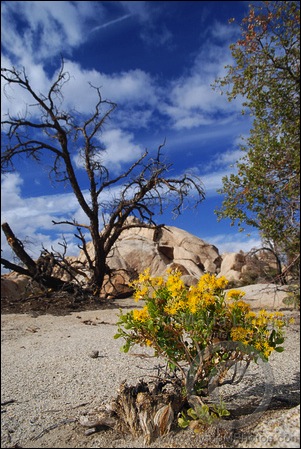

I clearly recall lying on my stomach on cold rock to get the right angle for this shot. Photographed at Joshua Tree National Park.

There are two reasons why people steal photographs and other content they find on the Web:

- They mistakenly believe that anything that appears on the Web is in the public domain. This is not true. Most Web content is protected by the same copyright law as the most recent Dan Brown masterpiece of fiction (yes, I’m being sarcastic) or Black Eyed Peas single (do they still call them that?) or Pixar animated feature film. When these people honestly don’t know any better, they’re making an honest mistake. But when they’re told they’re infringing someone’s copyright and they refuse to believe it, they’re being downright stupid and putting themselves in the next group of people.

- They simply don’t care about the rights of content creators. These people know that what they’re doing is wrong but they simply don’t care. Perhaps they think they’ll get away with it. Or that since everyone does it, the content creator won’t bother trying to stop them. They’re wrong. Many bloggers, photographers, and other content creators actively pursue copyright infringers — and win in court.

I follow many photographers on Twitter and have seen more than one of them complain about their work being used elsewhere without their permission. In many cases, a bunch of us will “gang up” on a copyright infringer to attack him/her for his actions in blog or photo comments. This usually gets some kind of result. A properly prepared DMCA Takedown Notice usually does a better job.

Just Say No to Flickr

In one blatant case I recall on Flickr, a woman was stealing photos from photographers all over the Web and passing them off as her own. If she really had such a huge, diverse library of quality photos, she’d be famous. But all she had was a big, diverse collection of quality photos she’d stolen from other photographers, removing any copyright notices she found along the way. It was quite easy to convince the powers that be at Flickr that she was a thief. Flickr closed down her account. Has she learned her lesson? Who knows?

The worst thing about Flickr is that if someone steals a photo and puts it on his/her Flickr account under a Creative Comments Attribution License, anyone else is free to use the image if they give the Flickr user credit. That means that not only is he/she making a photographer’s work “legal” to reproduce, but he/she will get credit instead of the photographer!

As you can imagine, I don’t use Flickr. It simply makes content theft too easy.

Why I’m Watermarking

I’ll be the first to agree that watermarking photos — putting a visible copyright notice on the face of a photo — can be downright ugly. Depending on how it’s done, it can really detract from the aesthetics of the photograph as a whole. That’s why I’ve avoided them for so long.

But the other day, I got an e-mail from one of Flying M Air‘s aerial photography clients. He’d given me permission to include some of his images on Flying M Air’s Client Photos page (since removed). Flying M Air has an unusual photo format. Each photo is brought into Photoshop, given a yellow background, white border, and drop shadow. It’s then tilted 2° or 3° to give it the feel of a photo album. I purposely use small images, not only to offer more room for text but to make the photos less useful to a thief. Unfortunately, one of his photos had been stolen and it appeared in a Flickr photo stream. The photographer was certain it had come from my site. He said that he’d given me permission to reproduce them, but only if I watermarked them. (I honestly don’t remember the watermark requirement.) To avoid problems in the future, I simply removed his photos from my site. If he experiences any more theft, it won’t come from me.

But the whole thing got me thinking. Here was a professional photographer whose work was being lifted from a third party site and being displayed on yet another site. He’d relied on me to watermark his work. Wouldn’t it have been better if he simply watermarked it himself?

And wouldn’t it be better if I simply watermarked my best work myself?

You might be asking why: what’s the purpose?

The purpose is education. While a watermark probably won’t deter a content thief who simply doesn’t care that he’s stealing from me, it might educate the person who thinks all content on the Web is free to take and use as desired. Or it might protect my work from the person who thinks that only those photos with a copyright notice are protected.

My client issued a takedown notice to the person who stole his photo from my site. The photo was immediately removed. I like to think that the person who stole it simply didn’t know any better. Now he does.

Zenfolio

I should mention here that in addition to my photoblog, I also maintain a library of images at a custom Zenfolio site. Zenfolio is a photo sharing site that offers a number of features a service like Flickr doesn’t offer. For example:

- I can have my own domain name (www.FlyingMPhotos.com).

- I can sell photos using format I specify — and actually profit from a sale.

- I can create custom watermarks that are automatically placed on each image for display.

- I can limit the sizes of photos that can be displayed.

- I can customize the appearance of my photo gallery pages.

I photographed these wildflowers near a mine site last February.

The list goes on and on.

Yes, I do pay an annual fee for this service. But I think it’s worth $100 a year to have control over how my photos are displayed and offered for sale. And I like the fact that my Zenfolio portfolio is completely separate from all others. On services like Flickr and Red Bubble (which I used to use), your photos are simply part of a much larger portfolio of diverse and often quality-challenged work. People who visit my portfolio aren’t exposed to that — unless they want to be.

I like the way Zenfolio places watermarks on images. They’re visible yet don’t need to jump out of the photo at you. I chose the same method for my photo blog; you can see it on all the images on this post. I used Photoshop to create the notice, applied an Emboss filter, saved it as a PNG with transparent background, and then applied it to photos with 20% to 50% opacity. Done.

What Do You Think?

I’d be very interested in hearing what other serious and professional photographers think about watermarking images. I’d also like to see examples of what photographers think are successfully applied watermarks. Use the comments link or form for this post to share your thoughts, horror stories, and links to one or two of your watermarked images.

I’m not interested in hearing from Internet trolls who want to criticize concerned photographers for wanting to protect their work. Or people who want to argue that Internet content is not copyrighted — get with the program already, folks.

Through the use of some new

Through the use of some new