Just a quick note another long, drawn out post to document a recent hive split and the results so far.

Last year, I split my original hive into 2 hives. I called it “the risky hive split” because of the way I did it — kind of haphazardly with my fingers crossed. I basically pulled a few brood frames with swarm cells out of an existing hive and stuck them in a new hive box with some honey and empty frames. The split worked because at least one of the queens hatched and took over. But that new hive was never very healthy and was the second to die after winter. The original hive was the first to die.

The actual size of this square is 1 inch.

Now you could say that they died because of the split. Instead of one strong hive, I wound up with two week ones. But I did the split in mid-July and prevented a swarm. The original hive continued to thrive. I think the reality was much more sinister. Both of those hives had terrible varroa mite infestations — I documented this with sticky boards in late summer. Although I did what I could to get rid of the mites, including drone frames, screened bottom boards, and miticide, I think the damage was done and the colonies were weak going into winter. The winter was harsh with few warm days and the bees simply didn’t make it.

Springtime at My Mobile Apiary

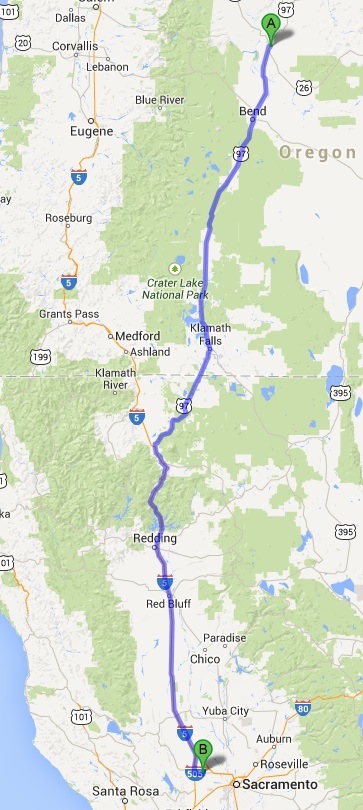

Fast forward to this year. Of my three hives, only my swarm capture hive survived the winter. Not only did it survive, but it was going like gangbusters within a few days of setting it up in my temporary home in the Sacramento area of California. (That hive, by the way, had very few mites in late summer. Coincidence? I don’t think so.)

Each hive must have a single queen and a whole bunch of worker bees. It might also have drones, but doesn’t really need them. (Strong women really don’t need men either, but I digress.) The queen’s job is to lay eggs to make more bees. The workers’ jobs are to do everything else — tend to the eggs and larvae (or brood), maintain the hive, guard the hive, gather pollen and nectar, and make honey.

If there isn’t a queen, no new bees can be added to the hive. Within a month or two, all the bees will have died and the colony will have collapsed. The workers instinctively know this. They also know if the current queen is sick and needs replacement (supercedure) or if the hive is becoming so crowded that half the bees need to move out with the queen so there’s room for a new queen to start fresh (swarming).

The workers have the ability to turn any egg into a queen when they think they’ll need one. They do this by forming a special elongated cell for the egg and feeding it a diet of royal jelly, which they make, until the cell is capped. After a longer-than-usual larval stage, a queen emerges. If there’s more than one queen in a hive, the strongest queen will kill the weaker ones.

I’ve done four pretty thorough hive inspections since arriving here and setting up the bees — including the initial setup/inspection about a month ago. The second inspection showed impressive brood development but not much in the way of honey storage. In addition, I was very surprised to see that the queen’s laying pattern covered almost an entire brood frame — not just the middle as most queens do. There were brood cells all the way to the side and bottom edges of each brood frame with just areas along the top and in the corners filled with honey.

The other surprise was how many of the frames were being used for brood. The deep body had just nine frames in it — a strategy I’d like to avoid in the future — and there was brood in six or seven of them. At that rate, I figured the queen would soon run out of space for brood and the bees would need more room for honey. So I placed a queen excluder atop the deep box, a spacer with an entrance on top of that, and a medium box with mostly drawn out — but otherwise empty — comb on top of that. The idea was to encourage the bees to move the honey upstairs, where I could pull frames for extraction and replace them with empty frames. The queen excluder would keep the queen downstairs. In theory, it should work.

It didn’t. On the next inspection, I found that the queen just kept laying eggs downstairs, making the hive ever more crowded, but the bees had not started to put honey in the medium super above them. I looked for signs of swarm preparation but found none. Just a whole lot of bees and a whole lot of brood.

That gave me the idea that they wanted to make bees. That was fine with me; I was hoping to go home with at least three active hives. Maybe I should try another hive split?

The Riskier Hive Split

Now, the last time I did a hive split, I had swarm cells — that means that the workers were already trying to make queens, likely in advance of a swarm event. What made that split risky is that I never actually found the queen. I just made sure that each hive had brood frames with swarm cells on them. I figured that the bees would continue to tend to those swarm cells until a queen emerged. If a hive wound up with more than one queen, they’d sort it out for themselves.

And that’s what they apparently did. They certainly didn’t swarm and I have no way of knowing which hive wound up with the old queen — or even if she was killed by a new queen.

But in this case, I didn’t have any swarm or supercedure cells. No future queen.

What I did, have, however, was the location of the queen. I found her on one of the three primary brood frames during my third inspection. I was prepared. I’d already assembled another deep hive box with brood and honey frames. I slid the frame with the queen on it back into her hive and then pulled out the other two primary brood frames, each of which had very young larvae in them. I can only assume there were eggs as well — the damn things are so small that I just can’t see them in cells against the yellow background. (Note to self: only buy black foundation for deep frames from now on.) I slid those frames with their bees into the new box and put empty brood frames from that box into the original hive. Then I took one of the honey frames full of bees and put that into the new box. In all, I probably put about 30% of the original hive’s bees and 20% of its brood into the new box. I closed up the new box and pointed its door 90° to the left (south)

What I was hoping, of course, was that the bees in the new hive would quickly realize that they were queenless and do something about it — namely, take a few of those cells containing eggs or newly hatched larvae and do what they needed to do to turn them into queens. That would be the best case scenario. The worst case is that they’d abandon the hive and find their way back into their old hive, which was sitting right beside them with its door pointing 90° to the right (west), leaving the brood untended so it would die.

Of course, you won’t find many bee books that tell you to do this. Most tell you that if you want to split a hive, you should buy a queen, put bees from an existing colony into a new hive box, and introduce the new queen to them. If they accept the queen — which they should if you do everything right — the queen will get right to work making more bees.

I had a few more things to do with the original hive before I closed it back up.

I had a drone frame in there and it was more than half full and capped, but I pulled it out and replaced it with a regular frame. Trouble is, it won’t fit in my RV’s freezer and I had to borrow freezer space at the airport office. Doing that once is okay, but I don’t think they’d like to see a new frame full of bee larvae every three weeks. (Yes, I did wrap it in a black plastic bag.) I’ll save the drone frames for when I get home and can access my chest freezer.

In the meantime, I’d bought a comb honey setup with shallow frames and wax foundation. Not knowing what else to do with it, I stuck it on top of the medium box on the original hive. Maybe they’d prefer that kind of foundation over the medium frames. (That would certainly make me happy, since I want to make comb honey.)

I closed the hive back up, put away my tools, wished the bees luck, and left them.

Throughout the week, I visited the hives. I saw bees coming and going from both hives, but far more at the original hive than the new one.

Progress Report

And that brings me to my most recent hive inspection, which I did earlier today. My main goal was to see what was going on in that new hive. Were there bees in there? Were they working? Most importantly, had they built queen cells?

I suited up and opened their box. I immediately saw bees inside — a good sign. I pulled out a few frames along the edges. No new brood — but I really didn’t expect any.

This photo shows a queen cell and some drone cells from last year. I didn’t take any photos of the queen cells in my new hive.

Then I pulled out one of the middle brood frames — one of the ones that had been inside the old hive box. I was thrilled to see queen cells on one side. I counted two of them. The other frame had five queen cells. This was looking good. I put everything back in place and closed it up. No need to disturb the bees any more than I needed to.

Of course, now I have a new worry. If the queen hatches successfully, will she find drones to mate with when she goes out for her mating flights? Maybe freezing that drone frame was a bad idea. (Cut me some slack; I’m new at this.)

The original hive, however, was a bit of a disappointment. The bees still hadn’t put any honey in either of the upper boxes. To make matters worse, they’d begun to fill the queen excluder with wax. I had quite a time clearing it out. Not knowing what else to do, I reassembled the hive the way it had been. If the new hive produces a queen and she starts laying eggs, I’ll put one of the honey supers on that hive.

In the Meantime…

A beekeeper with a pollination business here in California is selling his hives. He has 50 left and is selling them in palettes of four. I’ll be visiting him next week. Who knows? I might come back to the airport with another four beehives.