I take a week-long break from traveling to check on things back home.

– Introduction

– The Colorado River Backwaters

– Quartzsite

– Wickenburg

– Phoenix

– Home

– Back to the Backwaters

– Return to Wickenburg

– Valley of Fire

– Death Valley

– Back to Work

Long before I retrieved the Mobile Mansion from the sale lot to begin my snowbirding trip, I booked flights home from Arizona and Sacramento. My house sitter had vacation plans for the end of January at a time that coincided with a meeting of the writing group I belong to, as well as my need to get my FAA flight physical done. I figured I might as well come home while she was away. A quick flight search on Alaska Air’s website, armed with the latest frequent flyer special offer, yielded a surprisingly inexpensive round trip flight from Phoenix to Wenatchee for that week so I booked it, thus locking me in to doing the trip in the first place and coming home in the middle of it. The Sacramento flight I booked was for later, in February, when I’d go home to fetch my helicopter for work in California’s Central Valley.

The Trip Home

So that’s why I found myself standing at the curb in front of my friends’ home near Phoenix at 4 AM on a Wednesday morning, waiting for an airport shuttle with Penny and two packed bags.

My friends wanted to take me to the airport, but I could not ask anyone to drive me anywhere at 4 AM. So before we could argue about it, I booked and paid for the Super Shuttle. Cheryl warned me that they wouldn’t be able to find her house because Mapquest gave bad directions — and I verified that Google did, too — but I instructed the driver to take 27th Avenue when I booked the trip. Still, at 4:05 AM, I saw the van’s headlights on the other side of a dry wash it could not cross. (Why ask for special instructions if you’re not going to use them?) A frantic phone call to the Super Shuttle people got me in touch with the dispatcher. Ten minutes later, the van sped down the road, coming to a stop where Penny and I waited.

I had a 6 AM flight and, for a while, was worried that we wouldn’t get to the airport on time to deal with checking bags and going through security. But there was no traffic at that hour and activity at the airport was predictably light. My ticket had been upgraded to First Class — probably because of the early purchase and my “MVP” status on Alaska Air — so I got better counter service and didn’t have to wait on the longer line for security. By 5:15, we were waiting at the gate.

I don’t fly First Class very often — I honestly don’t think it’s worth paying a lot more for — but I will occasionally splurge if it’s a long flight and the difference in price isn’t outrageous. It’s always nice to get a free upgrade. I sat in seat 2A, put Penny’s travel bag under the seat in front of me, and settled into the very comfortable seat. It was nice getting a hot breakfast, but I skipped the complementary alcohol. In hindsight, I think a bloody Mary would have been nice.

SeaTac treated us to some typically rainy weather.

We got into Seattle early and my layover was just long enough to get Penny out of her bag for the walk to the gate for our connecting flight to Wenatchee. Then Penny was back in the bag and we were on the turbo prop to Wenatchee. We’d arrive at 10:22 AM.

And yes, that’s why I took a 6:00 AM flight out of Phoenix — so I could get the first flight into Wenatchee that day and have a whole day at home instead of sitting around airports.

Return to Malaga

I’d asked my friend Alyse to pick me up at the airport. Normally, I would have taken a cab, but it had snowed on and off during the month I was gone and I knew how bad my road could get. Yes, it was passable for any vehicle with good tires and a driver who knew how to drive on snow-covered roads. But who knew what the cab company would send? Besides, I wasn’t sure what condition my driveway would be in. I knew that one of my neighbors had plowed it at least once, but when? I was hoping to get close to my front door and wasn’t convinced that a cab would pull into a snowy driveway.

Alyse and her boyfriend Joe came in her four wheel drive pickup. I threw my luggage in the back and climbed into the back seat with Penny.

We talked about the snow. When was it going to go away? It wasn’t this snowy last year. Alyse told me that in the old days, it snowed like this all the time. She wasn’t the only person to say this over the coming week.

The roads in the Wenatchee area were clear. So were the roads going into Malaga and up toward my home. But my road? Completely snow-covered. Alyse flipped it into four wheel drive and started the last two miles. It wasn’t very slippery, but it was very thick with snow in some parts. It seemed that the association had plowed it seven times (so far) that winter. Unfortunately, the guy who does the plowing is cheap and you do get what you pay for. And the farther down the road you went, the worse it was. Although there were three houses beyond mine, mine was the last one that was occupied most of the time during the winter, so the last stretch seemed barely plowed at all. In fact, my driveway was in about the same condition as the road.

I was amazed by how much snow was still on the ground. I knew the temperatures had gotten into the 40s at least a few days and had assumed that most of the now had melted. It hadn’t.

But it was beautiful.

I shot this photo of my home from the road a day or two after I got home. It really is pretty with all that snow.

Alyse and Joe helped me get my bags inside. Alyse wanted to show Joe some of the finishing touches I’d put in the place, including the rustic wood trim over my stairway stub wall and the furniture my friend Don had made out of charred wood slabs. And the Pergo I’d laid. (They flip houses and are always looking for some nice architectural touches to bring up values before selling.) Then they left. I watched to make sure they got out of the driveway, then set about unpacking.

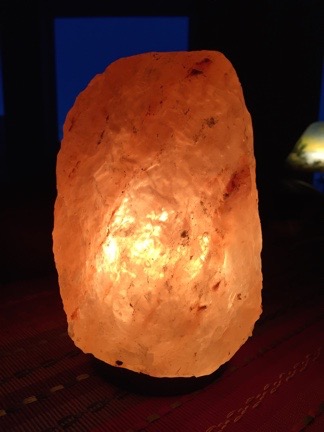

One of the things I brought home from Quartzsite is this Himalayan rock salt lamp. While I don’t believe in its purported health benefits, I do like the way it looks when illuminated. That’s one of my antique lamps behind it.

One of the two bags I’d brought home with me was the big folding rolling bag I’d bought years ago for the Australia trip I’d begun planning in 2011 and hoped to take with my wasband in 2012. (That didn’t happen, for obvious reasons.) It’s a neat piece of luggage: a very large wheeled duffle bag that folds down into a small package for storage. (I don’t think Eagle Creek makes them anymore because I can’t find it on their website.) I’d packed clothes into it when leaving on my trip in late December, unpacked in the Mobile Mansion, and stored it, folded up, in a cabinet. Then I used to to bring home a bunch of stuff I didn’t need with me, including including outdoor winter clothes and boots and a bunch of stuff I’d bought in Quartzsite for home. I didn’t have much laundry to do — I’d done most of it when I was in Wickenburg — but I had plenty of stuff to put away.

I checked on the chickens and was pleased to see I still had five hens and a rooster. No eggs. The shed still had water and cat food for my barn cat who was, as usual, absent. The housesitter had mentioned that the cat’s water froze once or twice and that surprised me because the heater I’d left in there for him was still running. It must have gotten very cold. I might insulate the shed over the summer so it stays warmer next winter.

There was no snow on my roof because it had all slipped down in front of my garage. Yes, I take credit for the poor design that causes this to happen.

Of course, the melting temperatures during the past week were just high enough to get the snow to slide off my two big roofs. On the south-facing side, that wasn’t a big deal because there was nothing there. But on the north-facing side, it slid down into a huge pile right in front of my four garage doors. That meant I had a shitload of shoveling to do if I expected to go anywhere in my Jeep. No rush to do that; I had put milk in the freezer and had plenty of food for the day — or even the week — so shopping wasn’t a big priority.

It was nice to be back in my nice, clean, warm home. It was nice to not have to worry about how much water or power I used (as I had when I’d camped off the grid in the backwaters and Quartzsite). It was nice to have fast Internet. It was nice to have a freezer full of foods I’d prepared and frozen for the days I didn’t feel like cooking and a microwave I could use to reheat them. Heck, it was even nice to have a television that I could tune into something.

I celebrated that first day home by eating a beef barley soup I’d made back in December and catching up on the Daily Show.

The Snow Bank

The next day, after doing odds and ends around the house, it was time to face the inevitable: the snow bank keeping my Jeep from exiting the garage.

My garage has five vehicle doors:

- The big one on the front (east side), which measures 20 feet wide by 14 feet tall, is for the RV garage. Because I didn’t need to use that garage after my Santa flight back in early December, I’d stopped shoveling the 22 x 35 (or so) concrete pad in front of it. The snow had kept accumulating since then, melting and freezing and then accumulating some more. I estimated I had about 14 inches of frozen snow there and no real need to shovel it.

- The four regular garage doors on the north side, which each measure 10 feet wide by 8 feet tall, are for my vehicles. The entrance to these garages is under my side deck, which is covered by an extension of the same roof that covers my living space. It’s a very big roof — roughly 52 x 36 feet — and built on a 3/1 slope. Because the space under it is mostly insulated, when the snow falls on it, it sticks. Until the temperatures warm up. Then the slow slides off — about six feet in front of the four garage doors below it. I was very fortunate that the snow didn’t slide off right before I left for my trip because I’d have to shovel my old truck out to make my departure. But my luck couldn’t hold out forever and the accumulated snow had dropped to a compacted “drift” 3 to 4 feet tall, 8 feet wide, and about 6 feet thick.

Fortunately, the Jeep lived in the very first garage bay. I put it there because the stairs up to my living space were in the back of that bay, making it about 5 feet shorter than the other three bays. The Honda lived beside it; that wouldn’t be back on the road until all the snow was gone in the spring. The truck lived in the third bay but it was back in Arizona. My little boat lives in the fourth bay and wouldn’t be coming out until the weather got sufficiently warm. It was a good thing these other bays didn’t have vehicles I needed to drive because the neighbor who’d plowed my driveway dumped all the snow in front of the last two bays. And that snow pile was more than 5 feet tall, 20 feet wide, and 20 feet thick. That’s a hell of a lot of snow.

At this point, I was about two thirds done making my way through the snow pile outside the Jeep’s garage bay.

So on Thursday morning, after a sufficient amount of procrastinating, I put on my winter boots and a sweatshirt and headed out the garage door with two shovels. I used the long-handled spade to break up the compacted snow and the snow shovel to move it in front of the Honda’s garage bay. It was slow going warm work. In an hour, I got about two thirds of the way through it. I was glad my Jeep was narrow; if I’d been digging out a space wide enough for the truck, I would have had a lot more snow to move.

I heard a vehicle on the road and ignored it, but when it got closer, I realized I had company. It was a pickup truck I’d never seen. It stopped in front of the garage bay and three people got out — my neighbors who had plowed my driveway not once but twice while I was gone.

We chatted and the husband, John, offered to come back with his plow and move all the snow away. He even offered to plow in front of the big RV garage. I said sure, fine, and was definitely willing to pay. But we got to talking more and more. The next thing I knew, he was back in the truck, using it as a battering ram to break through the snow separating my Jeep in the garage from the rest of the driveway. He sort of sideswiped it, letting the bumper break the snow and his front tire mashing it down into a shorter pile. This was not what I had in mind to clear out the garage bay, but he was having a great time doing it, laughing gleefully every time his truck hit it. When he’d finally broken through, I went at it with my shovel and he climbed out of the truck to help. He was extremely pleased that rubbing his truck against the snow had cleaned the lower side of it.

I can’t make this shit up.

It only took a few more minutes to clear the snow away so I could drive out. There was that hump to drive over and I really didn’t want it there, but it was so tightly packed that it would have taken me hours to clear it away. Besides, I knew my Jeep could run over it. I fetched some money for the other two tow jobs and his wife took it for him. He told me to call any time I wanted him to come back with the plow. He didn’t seem to understand that he could come back that day. And then I started thinking about it and realized that I didn’t exactly need the work done. And that I could save about $100 if I didn’t have it done. So I told him I’d call if I needed it done and they all drove off, happy.

I went to the store later in the day and got some groceries, including fresh milk and salad stuff. The Jeep started right up and handled the driveway and the road without any problems.

A Week at Home

I began regretting coming home about a day later. The weather turned cold again, staying pretty much right around freezing. We had some more snow and some of it melted away when the sun came out and shined on it. But there were a few days of January fog, which I find dismally depressing, and it was too cold and snow-covered to get anything done outside.

My do-it-yourself solution for mobile indoor scrap wood storage. Don’t laugh — it works and it was dirt cheap to throw together.

I did get stuff done inside, though. I did a bunch of cleanup work in my shop. I took an old wooden crate I had, put wheels on it, and set it up as a scrap wood trolley. This made it possible to store all the scrap wood I had indoors in a place where I could move it around to get it out of the way when needed. I vacuumed up all the sawdust my miter saw and table saw had left behind when I cut the wood for my loft guardrails — I’d used the table saw to cut the grooves for the wire fencing to fit into so there was a ton of sawdust on the floor from that. I worked on reorganizing my shop area and made some preliminary plans for another set of shelves in the storage end of the garage. I also planned the locations for a few more outlets I wanted to add on that side of the building. I’ll get the lumber and electrical parts I need for both jobs when I return in spring.

I finally finished the rail for my loft, which was required by building code. This narrow section of loft space over my closet gives me easy access to the high bedroom window facing south, which I pretty much leave open in the spring and fall.

With all the wood already cut and finished for the loft rail in my bedroom, I had no reason not to finish it up. So I spent an afternoon doing that. It came out remarkably well.

And I had just one tiny bit — the return — to finish at the top of the rail for my stairs so I knocked that off in about an hour. I even took out my sander and finished the surface a little better for another coat of tung oil.

Penny looked much cleaner — and smelled much better — after a bath.

I gave Penny a bath. After so much playing in the dirt along the river and in Quartzsite, she really needed one.

I joined my writer friends for our regular meeting. I’d missed the previous one and the one before that had been called off due to weather. It was good to see them all and share feedback with them on their work. And to hear feedback on mine.

I took care of chores in town one day. I got my FAA flight physical (passed) and some long overdue blood work done. I got some prescriptions refilled. I bought food for the chickens and my barn cat. I went to the airport office, paid a bill, and dropped off a survey. I arranged to park my Jeep at the airport when I went back to Arizona so I could drive myself home when I returned.

I caught up with some friends, too. I met with Megan for some wine on Monday afternoon and had dinner with Alyse on Tuesday evening. Bob was supposed to meet with us, but with the weather kind of nasty, he’d decided to go straight home from work instead. (Wimp.)

The Wild Rush at the End of My Stay

Suddenly it was Tuesday and I was getting ready to go back to Arizona the following morning. I still had a ton to do.

I’d promised the friends waiting for me in Arizona that I’d smoke up some ribs for them, so I dutifully defrosted four racks — which is the most my Traeger can hold — and prepped them for smoking. I would have put them on the grill before dinner with Alyse, but I was worried that I’d be gone too long and the hopper would run out of pellets. I figured I’d do it when I got home that evening. Unfortunately, my Traeger’s auger decided it wasn’t going to run in the 26° weather out on my deck. So I popped the ribs into the oven on a rack over a pan, set the oven to 225°, and let them slow cook there.

That was at 7:30 PM. I packed and cleaned up my home while I waited for the ribs to cook. It took 4 hours — just as it does on the Traeger. (Thank heaven I’d had baby backs in the freezer; St. Louis style take at least an hour longer.) I also made a batch of Honey Barbecue Sauce. It was midnight when I finally wrapped the ribs in aluminum foil and a big plastic bag and stuck them in the fridge.

All this time, I had my aviation radio going and didn’t hear the Horizon flight come in at 11:55 PM. That got me thinking that it hadn’t come in. My 5:40 AM flight is the same plane and when that plane doesn’t come in at night, the morning flight is cancelled. I got it in my head that the flight would be cancelled and couldn’t sleep until I’d spoken to someone at Alaska Air about it. Although she didn’t know if the plane was in Wenatchee, she didn’t see the flight being canceled.

At 12:30 AM, all packed and ready to go with my coffee maker set up to make coffee in my travel mug, I set my alarm for 3:10 AM and finally went to sleep.

Wednesday would be a big travel day.

To say I’ve been doing a lot of traveling this past year would be to make a huge understatement. I’ve been on more than 20 airline legs since September and expect to be on at least a few more before I finally settle down in my new Washington home.

To say I’ve been doing a lot of traveling this past year would be to make a huge understatement. I’ve been on more than 20 airline legs since September and expect to be on at least a few more before I finally settle down in my new Washington home.