Picking the right tool for the job.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about aerial photography work with helicopters and drones and thought I’d take a few moments to share my thoughts and conclusions. If you think one or the other is the perfect aerial photography platform, think again and read on.

My Helicopter Aerial Photo Experience

I’m a commercial helicopter pilot and have been one for about 17 years now. Of the modest 3,600 or so hours I’ve spent flying, a lot of it has been on aerial photography missions:

One of my favorite clients, Mike Reyfman, shot this photo of Horseshoe Bend near Lake Powell from about 3000 feet up. Note the tour plane, which was probably flying about 1,000 feet over the “shoe.”

One of my favorite clients, Mike Reyfman, shot this photo of Horseshoe Bend near Lake Powell from about 3000 feet up. Note the tour plane, which was probably flying about 1,000 feet over the “shoe.”

- Fine art photo flights over Horseshoe Bend, Lake Powell, Monument Valley, Canyonlands National Park, and the Four Corners area near Shiprock, New Mexico. (I’ve probably spent more hours with photographers over Lake Powell, mostly from 2006 to 2011, than any other commercial helicopter pilot. At one point, I could identify every point along the lake from an aerial photo.)

- High speed desert racing photo flights at the Parker 425 in Parker, AZ.

- High speed boat racing photo flights at Lake Havasu in Arizona.

- Bike racing photo flights in the Lake Wenatchee and Leavenworth areas of Washington.

- Automotive promotional photo flights over proving ground test tracks in Arizona.

- Architectural and construction photo flights in major cities like Phoenix and Las Vegas as well as remote areas such as Burro Creek in Arizona.

- Geographical photo flights along the Wenatchee and Columbia Rivers, Lake Chelan, and Stehekin in Washington, Colorado River in Utah, and Salt River in Arizona.

- Agricultural photo flights in the Quincy, George, and Wenatchee Valley areas of Washington.

- Wildlife photo flights over the Navajo Reservation and Verde River Valleys in Arizona.

- Nighttime panoramic photo flights over a crowded football stadium at night in the flight path of Phoenix Sky Harbor airport.

- 360° panorama photo flights over Lake Powell, Horseshoe Bend, Goosenecks, and Bryce Canyon National Park.

- Air-to-Air photo shoots with everything from another helicopter to the world’s largest biplane to a 747 outfitted for firefighting.

Each mission had a different purpose, a different focus (pardon the pun). Each required a different kind of flying, from 4,000-foot (AGL) hovers to low-level, high-speed chases in obstacle-rich environments. Some required top speed level flying just to catch a target, others required tight, often difficult maneuvers in a choreographed dance with the target. In each case, my helicopter and I were the tools the photographer used to get the shots he needed. The photographer provided instructions and I positioned us where we needed to be.

There’s nothing quite like chasing trucks through the desert with a helicopter.

There’s nothing quite like chasing trucks through the desert with a helicopter.

I love aerial photo work, especially the challenging high-speed work I did over desert race courses. There’s nothing that can give me a buzz more than chasing a trophy truck down a twisty dirt track 80 feet off the ground at 80 miles per hour, so close I can hear his passing horn when he comes up on a competitor.

My Drone Aerial Photo Experience

As I’ve written elsewhere in this blog, I was not happy when I started losing aerial photo work to drones. I fought back for a while but, as technological improvements in both the flying and photo capabilities of drones made amazing results easier to achieve, I eventually got on board. I bought my first drone last winter and got my commercial drone pilot certificate soon afterward. (Yes, if you can’t beat them, join them.)

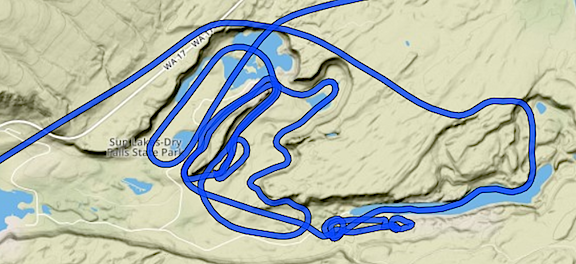

Here’s some footage from a recent practice flight around my home.

I don’t have nearly as much drone photo experience as I do helicopter photo experience, but I’m learning more every time I go out for a flight. I’ve been doing practice flights around my neighborhood, picking photo targets and flying around them for video fly-by shots and still images. I’ve also been taking my drone out to new locations to practice in target areas I find interesting. This winter, I’ll be using my drone to take photos of campsites out in the desert, as well as my activities on various Arizona lakes and rivers. Practice makes perfect and I’d like to get as good at drone photography as I am flying my helicopter on photo missions.

The Best Tool

I have, however, already come up against the limitations of drone photography, primarily related to speed, altitude, and operating temperature. I figured I’d list a few kinds of photo missions and explain which tool I’d pick and why.

Low-level, Low-Speed Operations

This is pretty much a no-brainer: when you’re operating below 200 feet at speeds of less than 20 miles per hour, a drone is probably going to be the better tool for the job. Yes, a helicopter can fly that low and that slow, but it’s far more likely to cause a disruption.

My best example of this is an aerial photo job I did for a local video production company. Believe it or not, they got the Wenatchee Symphony Orchestra to set up and play at dawn in a local park. The park had lots of tall evergreen trees and the orchestra was set up in a clearing. I had to get the videographer low enough for his closeups. The first time we passed, the helicopter’s downwash blew the sheet music off half the stands. (Oops!) A drone would have been a much better tool for this particular mission — and I actually said so during the flight.

Of course, blowing things around isn’t the only issue a low-flying helicopter can cause. It can also be a distraction to people on the ground. One of the flights I did for the same video company was a flight down Wenatchee Avenue not much higher than the highest buildings in the area. I had to fly sideways since the videographer was shooting out a side door. Although we got the job done, I think a drone could have done it better: it could have flown lower without distracting or disturbing drivers and pedestrians. The fight was short — we got the footage in less than 30 seconds — but a drone could have done the same thing without anyone on the ground even noticing it.

Better Choice: Drone

Low-Level, High Speed Operations

Of course, when you add speed, the drone simply can’t do the job. Consider my work chasing vehicles on land or over water. I’m usually flying at 50 miles per hour or more. (Seriously: on some of the boat shoots, I could not keep up; those things are fast.) I know that my drone’s top speed is about 22 miles per hour; even if a drone could go faster, could it keep up? I doubt it. And what happens when it gets out of range of the operator and his controller?

Better Choice: Helicopter

High Altitude Operations

While too many drone pilots seem to ignore drone altitude restrictions, they do exist and violating them is a good way to get into hot water with the FAA. Of course, trouble is a lot better than the possible alternative: flying into the path of another aircraft and causing a crash. As a helicopter pilot with no minimum altitude, I’m terrified that this might happen to me.

In the U.S., the FAA has established a maximum altitude for drones of 400 feet. Although it may be possible to get a waiver for a specific mission, it can take up to 90 days to get that waiver. How often do you know what you need to shoot 90 days in advance?

Helicopters, on the other hand, don’t have any altitude restrictions — other than those related to the helicopter’s performance capabilities. I’ve done photo flights where I had to hover at 9000 feet above sea level. Even if a drone could get up there, without a waiver it would not be legal.

Better choice: Helicopter

Operations Where Drones Aren’t Allowed

One of the things that really bugs me as a drone pilot is the number of places where drone operations are simply not allowed.

Some of them make sense — after all, do you really want to step up to the rim of the Grand Canyon and see a cluster of drones buzzing around in your view? Or attend an outdoor concert with drones flying back and forth over your head?

Meanwhile, drone restrictions in other places seem to make little or no sense. There are parts of Death Valley, for example, that are so remote they have few (if any) visitors and no wildlife. Why not let someone use a drone to take a few great photos that show off the barren wildness of the terrain?

Whatever.

The point is, there are places you can’t take a drone and, oddly enough, you can still take a helicopter. While flight over the Grand Canyon might be off-limits below 14,500 feet in most places, there are many national parks and other places where drone flights are prohibited but there are no restrictions on helicopter operations.

Let me be clear here: Most national parks are charted and pilots are requested to maintain at least 2,000 feet above the highest terrain in the area. Note the use of the word requested. I’ve written about this before. Although it is legal to fly lower in these areas, it’s not something you should do if you can avoid it. If you become a nuisance, you will be cited and will likely have to fight the FAA to keep your certificate. That’s why a lot of commercial pilots simply say no. Also, if people keep flying low-level through these areas, the FAA will make it illegal.

Until then — well, get those shots with a helicopter because without a waiver, you won’t get them legally with a drone.

Better Choice: Helicopter

As for flying low-level over crowds, that’s just plain stupid. Don’t do it with any aircraft, no matter what size it is.

Operation in Extreme Temperatures

All drones have operating temperature limitations, often due to battery capabilities. My drone, for example, will only operate in temperatures between 32°F and 104°F (0°C to 40°C).

My helicopter, however, doesn’t have any temperature limitations specified in the pilot operating handbook — although many people will argue that since performance charts aren’t available below -20°C or above 40°C, flight at those temperatures isn’t allowed. Newsflash: I’ve seen in-flight OAT temperatures of 112°F (45°C) in my helicopter and it still flew. I’ve also flown it when the outside temperature was about -10°F (-23°C) — the hardest part was getting it started; when it finally warmed up, it flew fine. (Unfortunately, it was a door-off photo flight; I don’t think I’ve ever been so cold in my life.)

The point is, if you need to do the shoot in very hot or very cold conditions, you might have to use a helicopter — or wait until conditions change.

Better choice: Helicopter

Operations Over Long Distances

I once had a photo shoot that included dozens of target locations along a 30-mile stretch of the Wenatchee River, a 50-mile stretch of the Columbia River, and the remote lakeside town of Stehekin on Lake Chelan. In my helicopter, we were able to knock off every location on the list in a total of three hours.

None of the flying was very special. It was relatively low and slow stuff, with some slow circling around points of interest. In fact, all of the shots could have been made with a drone. But that drone would have had to be driven to each location and launched for a flight there. It would have taken many hours to get all the shots and, if light was important — as it was for this shoot — the drone pilot/photographer probably wouldn’t have been able to shoot more than two to four locations each day. Add to that a half-day ferry ride to Stehekin, an overnight stay for the best light, and the half-day return trip and the project could have taken up to a month to complete.

Yeah, it would have been cheaper to do it with a drone. But time is money.

Better choice: Helicopter

Not Quite What I Expected

Want to become a commercial drone pilot? Start by learning all about the FAA’s Part 107. This book will help. Buy the ebook edition on Amazon or from Apple. Or buy the paperback edition on Amazon.

In writing this and thinking about the kinds of aerial photo flying I’ve done, I’m surprised at how few photo missions are better handled by a drone than a helicopter. It seems to me that drone aerial photo flights are pretty much limited to situations where the camera needs to fly low and slow. Anything else would probably exceed the capabilities of the drone or violate the law. That might be where a helicopter can get the job done.

Fortunately for commercial drone pilots, there are plenty of missions that require low and slow flight. So there will never be a shortage of work for them.

But what makes me very happy is the knowledge that drones will never fully replace manned aircraft — including helicopters — for aerial photo missions. After all, that’s the kind of flying I really like to do.

One of my favorite clients,

One of my favorite clients,  There’s nothing quite like chasing trucks through the desert with a helicopter.

There’s nothing quite like chasing trucks through the desert with a helicopter.