I tell yet another long backstory and get a few things off my chest. Sorry about the dirty laundry.

The other day, I did something I didn’t want to do: I bought a new monitor for my computer on Amazon.com.

The Monitor Backstory

It isn’t that I didn’t want to buy the monitor — I definitely did. Years ago, when I wrote books for a living, I had a wonderful computer setup that consisted of a 27″ iMac with a 24″ second monitor. I needed all that real estate for the work I was doing, laying out book pages on one screen and working with images, files, email, social media, and who knows what else on the other. It made my work easier and more pleasant to do, especially when I started getting involved in video projects for my helicopter YouTube channel, FlyingMAir.

But things change. I sold the helicopter and stopped doing videos. I bought a boat and started spending months on it at a time. I didn’t need a desktop computer so I traded it in for a new laptop. Along the way, I sold that second monitor, which, in all honesty, wasn’t that good anyway.

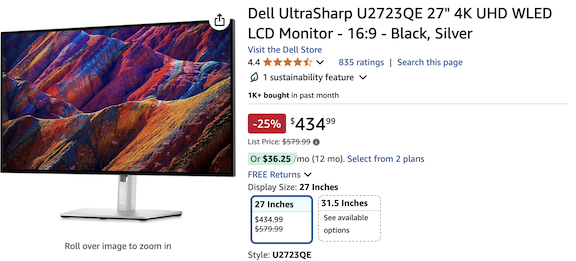

Here’s the marketing photo of the monitor I bought. Looks like a photo from Death Valley near Dante’s Point with a shit-ton of post processing and the saturation amped up, no?

But now I’m spending more time at home again, prepping to lay out another book, and making boating videos for my personal YouTube channel. So I bought a Mac Mini from Apple and bought a 27″ Dell UltraSharp monitor from Amazon to go with it.

The monitor is great and has more useful features than I need to cover here. It was working okay, but I really did miss that second monitor. So when I got home from my brief (comparatively speaking) trip south this winter, I decided it was time. I’d buy another monitor — preferably the same model — and set it side by side with the one I already had. It would make me more productive, I reasoned (whether rightly or wrongly). And yes, I’ll admit that the desire for some retail therapy weighed into the purchase decision.

And that brings me to Wednesday’s purchase.

The Amazon Backstory

I have been using Amazon.com since the only thing it sold was books. I was a Prime member when it was $49 (or maybe $39?) a year and all it got me was free 2-day shipping. I have spent thousands of dollars on Amazon over the years — sometimes more than $10,000 in a single year.

Sounds like I’m a real fan, right? Well, maybe I was but I’m not anymore. I dumped Prime when it got up to $149/year. (I think that’s what it is now, no?) I don’t watch TV and 2-day shipping is something Amazon stopped doing to my home back around Covid. I don’t like the way Amazon dominates the market and is putting smaller businesses out of business. I didn’t like the way “marketplace” vendors could be unreliable. I didn’t like the way search results — unless you had a specific make/model in mind — brought up so much crappy Chinese junk. And when it screwed up three of my orders right before Christmas, I started wondering why I was using Amazon at all. Surely I could just find stuff elsewhere.

So around mid-December 2024, I stopped buying at Amazon. Completely.

It wasn’t easy. You don’t realize how easy it is to fire up the Amazon app on your phone or tablet, find what you want (or think you want), and order it. With Amazon out of the picture, I had to source the things I couldn’t find locally elsewhere. It was a struggle. But I was succeeding. Up until Wednesday, I hadn’t ordered a single thing from Amazon. That’s about two months.

And I would have kept up the streak if it weren’t for the damn monitor.

Shopping for This One Specific Thing

- I wanted this monitor, not some other make or model.

- I wanted a new monitor, not a used or refurbished one.

- I wanted to buy from a reputable source, not some guy selling on eBay or Craig’s List.

- I know Best Buy will match prices, but not online. The closest Best Buy is a 2 1/2 hour drive from me.

- Costco does not carry every single make/model of monitor and I am not a Costco member anyway.

I really did think this through. This post might be long, but it doesn’t include every single thing I did and thought about this.

You see, I wanted the exact same monitor. I knew it would work well with my Mac. I confirmed that it could be daisy-chained, via USB C, to the one I already had. I knew that my little Mac Mini could support two UHD displays. Not only that, but because they were identical, they’d line up perfectly, side by side, on my desktop, making a seamless ultra-wide monitor with plenty of easily accessible real estate.

So I fired up Duck Duck Go — my current search engine of choice; don’t get me started on Google — and put in the monitor’s model number: U2723QE. Of course, Amazon appeared at the top of the search results, but I ignored it. I figured that I’d buy it at B&H, which is where I’d seen it at a slightly higher price than Amazon in autumn.

But that price had gone up. And, to make an already too long story a tiny bit shorter, I’ll summarize my shopping experience: the monitor was more than $100 less on Amazon than anywhere else. And I think I looked just about everywhere.

Although most pricing I saw was in the $540 to $590 range, I actually saw this monitor for more than $600 on AliExpress, which someone on social media suggested.

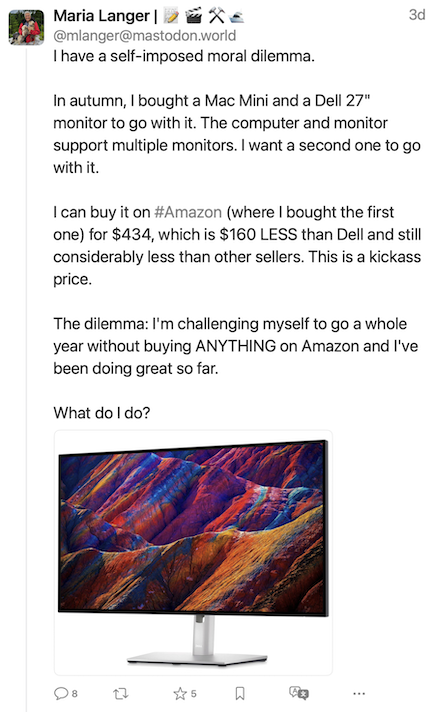

My Mastodon post. Imagine me getting the whole story in less than 500 characters!

I stressed over this purchase. The way I saw it was that I had two choices: (1) I could save more than $100 by breaking my No-Amazon streak and buying it on Amazon or (2) I could skip buying it. There was no way I was going to spend $100 more than I had to.

I discussed this dilemma on my social media network of choice, Mastodon. The replies started coming in. The general consensus was that avoiding Amazon purchases when possible was a good thing. But when I needed to make a purchase and Amazon’s price was far better than anyone else’s, I should just go for it.

I posted this on Mastodon on the thread about my self-imposed moral dilemma.

So I did.

And Now to the Point of this Post

All that is backstory. What would one of my blog posts be without backstory?

It was one of the replies to my post about the purchase that really got under my skin. I don’t want to put the poster in the spotlight because maybe that person didn’t mean to trigger me. But I was definitely triggered and that’s what this post is all about.

The reply was:

You could always donate a portion of the money you saved to an organization you support…

I was (possibly unreasonably) offended by this.

The main and somewhat obvious reason this might offend me is the insinuation that I don’t normally contribute to charitable organizations. That cannot be farther from the truth, as I attempted to make clear (with possibly some humor?) in my response:

The organization I support right now is my grocery bill, which was $200 yesterday for one person for one week. And I didn’t even buy eggs. ;-)

Throughout the year, however, I donate to NPR, Wikipedia, World Kitchen, Pro Publica, Goodwill, the Humane Society, and others. That comes to a lot more than what I saved today.

Ben had it right: a penny saved is a penny earned. The more I save, the more I can spend elsewhere, whether its on me or for charitable donations.

(The Ben I’m referring to here is Ben Franklin, of course. He was a smart guy, even if he never really did say “A penny saved is a penny earned”.)

But the deeper reason it offended me was because I saw it as someone trying to tell me how to spend my money — and that is a particularly sore spot with me.

Don’t Tell Me How to Spend My Money

The way I see it is this: I earned everything I own, either through hard, smart work or through good investments. No, I didn’t get everything right, but I got enough right to put me where I am today as a financially secure home owner with enough money in the bank to make money one of my lesser concerns in life. There’s no generational wealth propping me up — as a few people with giant chips on their shoulders seem to think. Since graduating from college back in 1982, I have never asked for or received any financial help from anyone in my family or elsewhere, no matter how much I needed it. (Well, there might be two exceptions to this if you count two loans after my divorce, each of which I paid back in full with interest within 5 months. I don’t.)

Here’s a blast from the past: on November 23, 2004, I took my sister and brother to the Robinson Helicopter factory for a tour. By an amazing coincidence, it was the same day they put my helicopter on the assembly line. Here I am standing next to hull #10603, holding a photo of a mockup based on a friend’s helicopter.

One of the ways I got to financial security was by making enough good financial decisions. The purchase of this monitor at Amazon for a savings of $100 is an example on a micro level. The purchase of a $346K helicopter, straight from the factory, that formed the basis of a lucrative 15-year career as an agricultural pilot is an example at a more macro level.

I spend my money the way I see fit. Yes, I have three vehicles, but the newest one is 12 years old. (The oldest is 26 now.) They all run, they all serve their purpose. And they’re all paid for. Why should I replace any of them if they’re doing what I need them to do? Why would I want to spend money on something with no real benefit? I’m not trying to impress anyone with what I drive. Why should I?

I’d rather have three old vehicles in my garage than just one with a loan on it.

Do you realize that the money I saved by not buying a new (to me) vehicle every two years — as my wasband was so fond of doing — is probably why I was able to pay off the mortgage on my home in less than 10 years? Do the math, folks. Home ownership might be more within reach than you think if you just adjust what you’re spending your money on.

And that’s the point. We all need to decide what’s important to us. It’s more important to me to have financial security with a paid-for home than to drive something new and flashy every few years. It might be more important to you to get your kid into a special school than to buy a home. Or more important to buy assets or get specialized training to build your business than take a vacation in Europe. We need to make our own decisions — and to respect the decisions of others.

The Sore Spot

Two and a half years ago, after spending a total of 10 weeks with two different boat captains on their boats along the Great Loop, I decided I wanted to cruise the Loop in my own boat. I had sold my helicopter and my charter business and had money to spend on a relatively new (but admittedly costly) “pocket yacht” that would meet my needs. I was very excited about the purchase and my upcoming journey. I wanted to share that excitement with people who meant a lot to me.

This is one of the photos on the brokerage website. I have a fondness for red, but that’s not what drew me to this boat. It was absolutely perfect for me — and a good deal, to boot.

But rather than them accept my purchase decision, they decided that they needed to tell me what a bad idea it was and to tell me what I should do instead. Their reaction made a few things clear:

- They didn’t know me very well. This is nuts considering I already had a track record of doing unusual things.

- They didn’t trust my ability to make my own financial decisions. This is also nuts given that I’m probably in better financial shape than they are.

- They thought they had the right to tell me how to spend my money. This is also nuts given that neither one of them did very much of interest with theirs.

This situation put a rift in our relationship that has yet to be mended. I was offended by their stance and made it clear to them. They have neither apologized nor made any efforts to repair the rift.

And this is what makes people telling me how to spend my money a sore spot.

I should mention here that, like the helicopter, the boat and the experiences it has made possible have given my life a new trajectory at a time I really needed one. I completed the 8000+ mile Great Loop trip and am working on a book about it. I’ve already written articles about it. I’ve become a USCG licensed boat captain and have already done some paying work for people who needed training on their own new boats and have secured gigs with at least two boat training organizations. I’ve become a certified boat instructor for single and twin engine power boats. And I’ve put my boat — which is a valuable asset, after all — into a charter program where it will earn money for me this coming boating season and possibly seasons beyond. None of this would be possible if I had not bought the boat that they told me not to buy.

They might be satisfied sitting at home, pulling pages off their calendars as the days of our lives tick by, but I’m not.

Are you still reading?

This post has been an unusually circuitous drive. Like so many of my blog posts these days, I wrote it, in part, to clear my mind of things that were bothering me. Someone insinuating that I didn’t make charitable contributions — by suggesting I do so with the savings on a computer monitor purchase — both bugged and triggered me. I felt a need to get this — including the dirty laundry that went with it — off my chest.

I guess the message I have for you is this: money is probably one of those topics we shouldn’t be talking about, like religion and politics. If you feel the need to tell someone how to spend — or not spend — their money, why not hold back? Unless the person is making a lot of seriously dumb decisions that are causing financial harm, they probably don’t need or want your advice.

Instead, why not take a closer look at your own spending habits and how they are serving you?

“Advice from a Raven” was different, though. Each of its seven points rang true with me:

“Advice from a Raven” was different, though. Each of its seven points rang true with me:

Here’s my favorite unedited cell phone shot from the visit. Note the sunlight on the canyon wall at the top left of the photo. I was waiting for that light to get to the falls, but it never did. The Nikon version of this shot shows a wider field of view and the composition is a bit better.

Here’s my favorite unedited cell phone shot from the visit. Note the sunlight on the canyon wall at the top left of the photo. I was waiting for that light to get to the falls, but it never did. The Nikon version of this shot shows a wider field of view and the composition is a bit better.