Dangerous, but if you have good hover skills and use caution, not very difficult.

For years, I used a tow bar made by Brackett Aircraft Company in Kingman, AZ, along with a golf cart or other tow vehicle to move my helicopter in and out of the hangar. With the golf cart gone, I began using my ATV, a 1999 600cc Yamaha Grizzly as the tow vehicle.

Ground handling of helicopters with skid landing gear — i.e., most helicopters — is not fun. It generally requires attaching wheels and doing a bunch of lifting and pushing. Sometimes multiple people are required. Even if you have other equipment to help with that lifting and pushing — I used a tow bar with tow vehicle for 14 years — you still have to do a bunch of setup (or tear down) every time you need to move the aircraft.

So you can probably imagine how glad I was to finally get my own wheeled landing platform (or tow dolly). I got it back in 2013 in trade for a golf cart I owned and I set it up for the first time in October at my new home. You can read much of the back story here.

In this post, I want to talk a little about landing on a wheeled platform like mine and the things a pilot needs to keep in mind when she does it.

A Little about My Platform

Here’s my platform, before landing the helicopter on it for the first time.

My tow platform is extremely heavy duty, made of steel tubing with a wooden deck. It has three rows of four solid wheels. The first two rows of wheels pivot.

The platform is 9 ft 4 in wide. It was built for a Hiller. The skids on my R44 are 6 ft 4 inches apart. That gives me 1-1/2 feet of extra space on either side.

The deck was once painted and included a wide orange stripe down each side that marked the ideal place to plant the Hiller’s skids on landing. My friend, who had it built to his specifications, had a bad experience with it early on. It had been parked out in the Arizona sun with the helicopter on it when my friend and his wife got in and prepared to depart. The sun had made the paint soft and one of the skids stuck to the deck. My friend narrowly missed having a dynamic rollover as he attempted to take off. This unnerved him so much that he stopped using the platform and sold it. The folks who bought the platform stripped off much of the paint to prevent that from happening again. That’s mostly why it looks so ratty on top.

The deck does not stretch all the way across the platform. Instead, there are two separate sections with a gap between them. I suspect that my friend designed it this way for weight and cost reasons, but, in all honesty, a solid deck wouldn’t be necessary anyway. If you landed with one skid in the middle of the deck, the other would be hanging out in space over the side of the deck. You’d never land that way, so why put a deck in the middle?

The top of the platform is about 18 inches off the ground. This is nice and low.

This is what I’m dealing with. As I write this, I’ve landed on it three times, including once in the dark. My only raised platform experience prior to this had been in the early 2000s when I landed an R22 on an 8 x 12 flat bed trailer.

Assessing the Suitability of Your Platform

Not all dollies or trailers are suitable for landing a helicopter on them. And a dolly or trailer suitable for one helicopter might not be suitable for yours. Here are a few points to consider, mostly in order of importance.

- Weight capacity. Is the platform capable of supporting the weight of your helicopter and then moving that weight? You wouldn’t want to land on anything you could break just by landing on it. And when considering this, remember to keep in mind that you might occasionally have harder than usual landing.

- Size, especially width. The platform must be large enough for your skids to fit comfortably on it with room to spare, especially on either side. The size of the platform as related to your helicopter skid width is what will determine how much room you have for error. The more, the better. As I mentioned above, I have about 18 inches on either side. I don’t think I’d want much less than that.

- Surface smoothness. It’s very important to have a smooth surface to land on to eliminate (or at least reduce) the possibility of dynamic rollover if you happen to drift while setting down. I highly recommend avoiding putting anything on the surface of the platform — including tie-down loops — if you don’t need to. If it’s a trailer for transportation of the helicopter, try to install the tie-down hardware after the helicopter is securely on the deck.

- Existence of Rails. If the platform or trailer has raised edges or rails around it, you are asking for trouble. Drifting into one of these rails while under power is a great way to get into dynamic rollover. Avoid landing on any surface with rails or raised edges.

- Height. My opinion is that low is better than high. I think that a lower platform will give you a lower center of gravity once you’ve landed on it. Seems smart to me. Another limitation is the total height of the helicopter on the platform — will you still be able to get it into you hangar? My garage door is 14 feet tall for a reason.

- Ability to secure. Locking wheels or brakes are a great feature. Use chocks if you can’t lock the platform’s wheels.

Beware of platforms or trailers designed for some other use and converted for helicopter use. Make sure a trailer is suitable before landing on it.

Choosing a Landing Zone

If you’re landing on a movable platform, you can pretty much specify where your landing zone will be. Or not.

In my situation, my landing zone possibilities are extremely limited. I have a 22 x 30 foot driveway apron. Beyond it is dirt or gravel. All wheels of my platform must remain on the concrete. And because the driveway apron is adjacent to my building and my helicopter’s main rotor blades extend past the edges of my platform, the platform must be as far away from the building as possible. So there’s only one place I’m going to be able to land — at least until I get more concrete poured — and it gives me just enough clearance to feel that I can operate safely.

My landing zone. I usually move the platform a little closer to the edge of the driveway now that I have good chocks.

But if your platform is at an airport or heliport, move it into a position that will give you plenty of clearance to come and go. I’m talking about clearance from obstacles such as buildings and wind socks as well as clearance from where other aircraft might be parked or people might be standing/walking/watching.

Securing the Platform

It’s vitally important that the platform be positioned on relatively level ground and secured so it does not move while you are taking off or landing.

My platform does not have brakes. None of the wheels lock. I use two methods to secure it in my landing zone:

- Set the brake on the ATV. My Grizzly has brakes and I always set them when I park it with the tow platform attached. I also leave the ATV in gear, which makes it less likely to roll if the brakes are released.

These are some seriously heavy-duty chocks.Use heavy duty chocks. I bought a set of hard rubber chocks from Amazon. These aren’t the crappy yellow plastic ones I have for my RV or flatbed trailer. I chose this type because rubber is less likely to slip on the concrete surface of my driveway apron and because they’re so beefy that the platform wheels and weight would not be able to damage them.

Note that I use both of these methods — not one or the other.

Noting Weather Conditions

I shouldn’t have to point this out, but it is important so I will.

Weather conditions should determine whether a takeoff or landing from a platform is even possible to conduct safely. For example, I would not attempt a landing on my platform in strong crosswind or tailwind conditions. I just don’t have enough space to give me the buffer I’d feel comfortable operating in. Fortunately, however, I have another place on my property that’s suitable for landing in almost any weather, so if things were questionable, I’d land there.

If you’re positioning your platform for takeoff and you have a lot of options, position it so the helicopter is pointing into the wind. This will make takeoff safer and easier. Then don’t assume your landing will be just as easy. If the wind shifts, picks up, or gets gusty, conditions will be different. Pay close attention to this before making your landing.

Also heavy on my mind this winter season is snow and ice. It’s my job to keep both my concrete pad and platform clear of anything that might cause the helicopter’s skids or the platform itself to slide. I have a good snow shovel and plenty of ice melt pellets. But if snow or freezing rain comes while I’m out on a flight, I will not land on a snow or ice covered platform. You probably shouldn’t either. Actually, we probably shouldn’t be flying in those conditions anyway, right?

Positioning the Skids

When you land on a platform, the positioning of your skids when you set down must be precise.

Before I landed on my platform for the first time, I measured it and my skids numerous ways. I needed to know where to place the front of my right skid — which is the only one I can see when I’m landing — to ensure that the helicopter was relatively centered on the platform without the skids hanging off the back. Remembering my friend’s paint problem, I decided to keep it simple. When I figured out the right spot to place the front curve of my skid, I took a can of spray paint and painted an arrow. If I kept the skid inside the thick landing stripe my friend had painted — which was still visible, despite most of the paint being removed — and lined up the curve with that arrow, I’d be good.

So I’m basically allowing myself about 6 inches of wiggle room in any direction.

Knowing that there was no deck in the middle of the platform bothered me for awhile — until I realized that as long as one skid was on one deck, the other skid had to be on the other deck. How did I know? I measured about six times. This really reduced my stress level when landing.

Of course, landing straight on the platform is also important — mostly so the helicopter will line up properly to be parked inside the building. In some instances, I can fix a crooked landing by getting light on my skids and applying some pedal. But this can be an extremely dangerous thing to do. If either skid were to catch on something, dynamic rollover would be possible. More on that in a moment.

The other thing to keep in mind when landing on a platform is how the skids will touch down. An experienced pilot would know this. For example, if I’m light on fuel and flying alone, I know that the rear right skid will touch down first, followed by the rear left skid. Then front right and front left. When I landed my R22 on that trailer years ago, I actually loaded a passenger so I’d be more balanced. (I was a much less experienced pilot back then and needed — at least mentally — a level aircraft.)

Why is this important? Well, the first time you do this, you’ll likely be a bit stressed out. Knowing, in advance, how the helicopter will touch down will eliminate any surprises when you actually do touch down on the surface. And once you touch down, it’s important to keep flying it down until the skids are firmly on the platform. You’re not done until the skids are flat on the platform.

I shouldn’t have to point out that excellent hover skills are required for landing on any platform. If you can’t set a helicopter down firmly on its skids without drifting in one direction or another while doing so, you have no business attempting to land on a trailer. This is not a task for a low-time pilot or one new to the make/model of a helicopter. Perfect your hovering skills before trying this at home, kids.

Using Extra Caution at Night

What prompted me to write this blog post was my surprise success landing my helicopter on my dolly at night just the other day. My landing zone is not (yet) lighted at night because construction on my home is not complete. I’d taken off around noon and fully expected to be back before it got dark. But the charter flight went long — as they so often do — and the sun was setting when I fired up the engine for the return flight. During the hour it took to complete that flight and drop off my passengers, it had grown quite dark.

I had already told myself that if I did return after dark, I’d land in my backup landing zone and move the helicopter the following day. But with unseasonably cold temperatures, I was unwilling to leave the helicopter outside overnight unless I had to. I’d had a bad experience back in 2011, trying to get the helicopter started when the temperature was -7F (-22C). It wasn’t expected to get that cold, but I didn’t want to deal with a battery charger and heater out in the yard the next morning. I decided to try landing; if I didn’t like what I was experiencing, I’d climb out, reposition, and land in that backup landing zone.

Approaching my home in the dark was not fun since I hadn’t left any lights on. I live in a very dark area and there was no moonlight. That I was able to find my place at all is due to my neighbors to the west having quite a few lights on their back porch. Once I got closer, I saw the solar lights I’d positioned along my driveway. Since my driveway is also my approach route, I was able to get into position for a good approach.

My skid was within the orange paint and only about 4-6 inches back from the arrow. This was my second best landing on the platform. The green light is cast from the position light on my side of the helicopter.

My helicopter’s two landing lights are quite bright, so I had no trouble seeing my platform. The only drawback was the dust cloud that got kicked up when I got closer. I patiently waited for it to clear — it only took a few seconds — before making my first attempt. I was extremely pleased when I was able to get the skids right over the decks and set the helicopter down straight on the first try. I even took a picture.

Would I do this again? Probably. But you can bet I’ll get some lights installed soon.

What Can Go Wrong

But I cannot overstate how easy it is for things to go horribly wrong when you land on a platform like my dolly or a trailer. And that brings me to this accident report from June 24, 2004.

In this case, a pilot who had purchased a trailer to use to transport his Bell 206B (JetRanger) helicopter was practicing landing on it. He’d tried and failed several times and thought it might be due to weight distribution. So he added fuel to help balance it out and tried again.

Here’s what happened:

In a written statement, an air traffic control specialist reported that he observed the pilot make three or four unsuccessful attempts at landing the helicopter on the transport trailer about 45 minutes prior to the accident.

In statements collected by the Mesa Police Department, witnesses reported observing the helicopter land on the trailer. As the helicopter began to liftoff the trailer surface, the left skid caught on the trailer, resulting in a dynamic rollover and collision with the ground.

I’m sure it didn’t help that he was doing this at night, although he was at an airport and I think it’s safe to assume that there was some light available.

The main problem seems to be that the trailer wasn’t really suitable as a platform for landing a helicopter. According to a witness who was a friend of the accident pilot:

During a telephone interview with a National Transportation Safety Board investigator, the friend of the pilot further added that the pilot had recently purchased the trailer, and was not experienced at maneuvering the helicopter onto it. He described the trailer as a modified boat trailer, with an open and trough-shaped platform, which he did not think was suitable for safe takeoff and landing operations. He opined that during the accident sequence the helicopter’s left skid caught on one of the numerous “D” shaped rings affixed to the platform surface. He added that at the time of the accident sky conditions were dark.

(Oddly, my friend who had my platform built now lands his helicopter on a transport trailer that requires him to put the skids in troughs built into the trailer. You couldn’t pay me enough money to try to land a helicopter on that trailer. )

This isn’t the only accident related to landing on a trailer or mobile platform. It’s just the one I was familiar with, mostly because a EMS friend who responded to the accident reported that the helicopter’s transmission had crushed the pilot’s skull in the crash. (At least he died quickly.) Here are a few others:

- ERA13LA308, June 29, 2013 – student pilot seriously injured and helicopter destroyed when helicopter drifted backwards when landing on a trailer.

- CEN12CA643, September 18, 2012 – helicopter consumed by post-crash fire when helicopter slipped off platform during landing.

- CEN11CA627, August 26, 2011 – helicopter destroyed when pilot experiences dynamic rollover on takeoff after forgetting to remove a tie-down clamp.

- WPR10CA470, September 25, 2010 – helicopter destroyed when pilot lands on trailer parked on uneven terrain and tail rotor hit the trailer.

- WPR10LA354, July 16, 2010 – 1 killed, 3 seriously injured, and helicopter destroyed when helicopter fell of trailer during landing. Note that pilot was attempting to adjust helicopter position with helicopter “light on its skids” when accident occurred. (I told you it was dangerous.)

- ERA09CA485, August 26, 2009 – the helicopter was destroyed when lifting off from a dolly with the GPU still attached.

- WPR09CA338, July 11, 2009 – helicopter destroyed when pilot experienced dynamic rollover while attempting to lift off from a trailer.

- CEN09LA202, March 11, 2009 – two people seriously injured and the helicopter was destroyed when skid is hooked under trailer while attempting to land on the trailer.

- NYC07FA029, November 15, 2006 – the pilot was seriously injured and the helicopter was destroyed when the helicopter landed with just one skid on a trailer and experienced dynamic rollover.

- SEA05CA104, May 23, 2005 – the helicopter was destroyed when its skid became caught under a trailer lip during takeoff in gusting crosswind conditions.

- NYC04CA199, August 27, 2004 – the helicopter was destroyed by dynamic rollover caused by a stuck skid during an aborted landing to a dolly in the dark.

- MIA04LA061, March 17, 2004 – the helicopter was damaged when it crashed during an attempted takeoff from a dolly. Pilot refused to cooperate with investigators, so facts are scarce. Alcohol may have been involved.

- ATL04LA076, February 21, 2004 – the helicopter was destroyed when the dolly moved while the pilot was attempting to land on it.

- FTW03CA233, September 28, 2003 – the helicopter was destroyed when it “hung up on something” during departure from a trailer.

- FTW03LA166, June 4, 2003 – the helicopter was destroyed when it experienced dynamic rollover when attempting to depart from a trailer with a tie-down strap still fastened.

- IAD03LA042, March 27, 2003 – the helicopter was destroyed when the pilot attempted to land on a dolly after experiencing engine trouble.

I found these for searching within the past 10 or so years for accidents that include the word “trailer” or “dolly.” I bet there are others. But this is enough to teach us from other people’s mistakes.

In Summary

Landing on a platform or trailer isn’t difficult if you have good hovering skills, approach the situation with caution, stay focused on the task at hand. Position the skids over the trailer before setting down firmly. Keep the possibility of dynamic rollover in mind all the time.

The only other thing I want to add is this: if your platform landing zone is difficult — and I consider mine more difficult than most — do it alone. There’s no reason to put passengers at risk when performing any advanced or potentially dangerous maneuver. That’s my two cents on this subject, anyway.

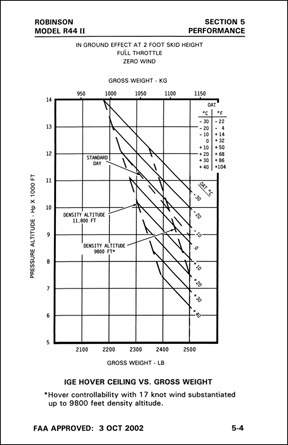

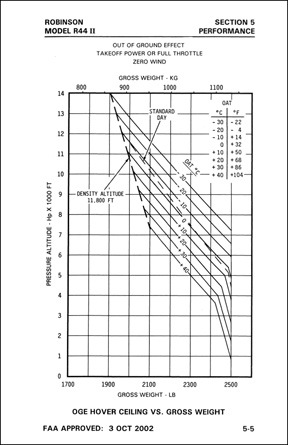

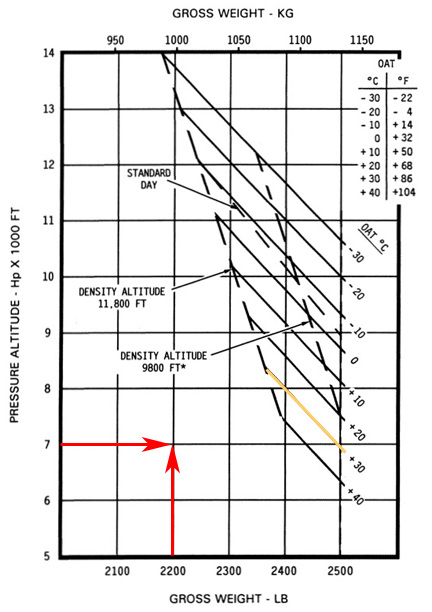

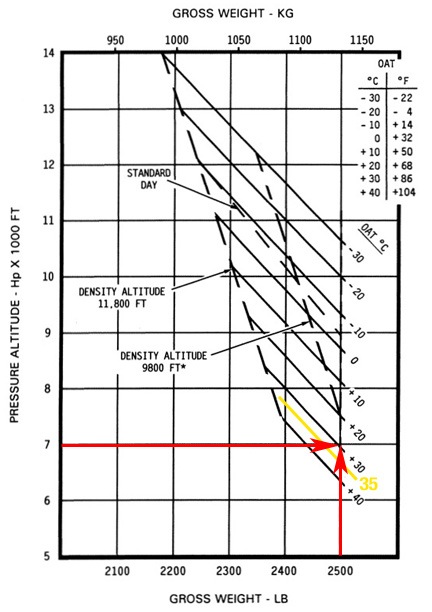

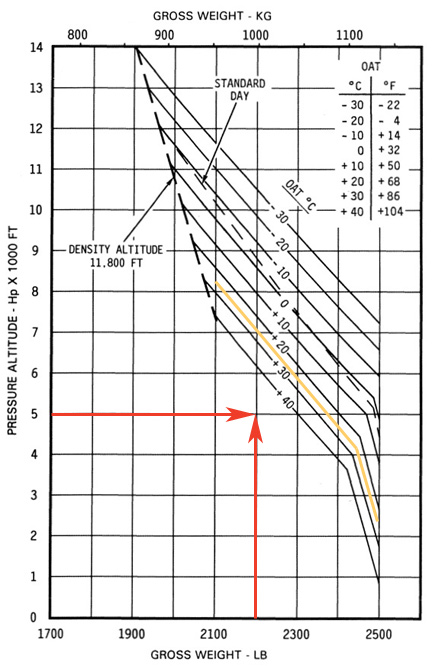

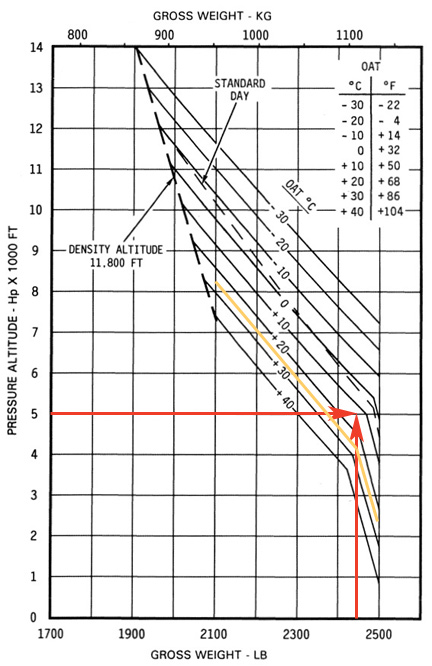

A look at the performance chart for an R44 (Raven I) makes it pretty clear why the pilot had trouble maintaining altitude at slow speed. At max gross weight on a 30°C day, the helicopter can’t even perform an out of ground effect (OGE) hover at sea level, let alone nearly 5,000 feet. That means it would have to continuously fly above ETL (approximately 25 knots airspeed) to stay in the air. At slow speed, a turn into a tailwind situation would rob the aircraft of airspeed, making it impossible (per the performance data, anyway) to stay airborne.

A look at the performance chart for an R44 (Raven I) makes it pretty clear why the pilot had trouble maintaining altitude at slow speed. At max gross weight on a 30°C day, the helicopter can’t even perform an out of ground effect (OGE) hover at sea level, let alone nearly 5,000 feet. That means it would have to continuously fly above ETL (approximately 25 knots airspeed) to stay in the air. At slow speed, a turn into a tailwind situation would rob the aircraft of airspeed, making it impossible (per the performance data, anyway) to stay airborne.