It’s not as tough as you think.

When I was learning to fly back in the late 1990s, my flight instructor babied me when it came to radio communication. He did most of the talking. Because I wasn’t forced to talk on the radio during my training, I didn’t get as much practice as I should have. As a result, my radio communication skills were weak — to say the least.

Although I really like my original flight instructor — and still stay in touch with him after all these years — he really wasn’t doing me any favors by handling communication for me. That became apparent when I went through my commercial pilot training and got my commercial pilot certificate. Although I could fly to FAA-established standards, I was a nervous wreck when it came to using the radio.

I eventually learned by doing it. After all, there was no CFI along with me to do the talking, so I had to do it. It took about a year for me to relax and even more time to realize that it wasn’t such a big deal after all.

Misconceptions

The big misconception among pilots in training is that they must use a certain vocabulary and say things in a certain order to communicate with ATC. That is simply not the case.

The goal of radio communications is to simply communicate. How you say it doesn’t matter much as long as the message gets across and two way communication is established when needed.

The Basics of Making a Radio Call

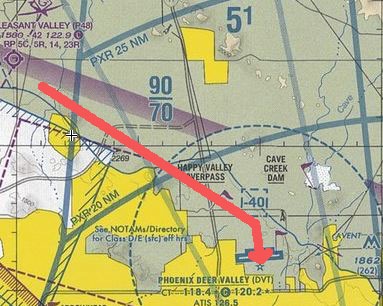

Here’s an example. Suppose I’m flying from Wickenburg to Deer Valley Airport. Wickenburg (E25) is class G, so the only talking I need to do is on unicom for position reports, etc. Deer Valley (DVT) is a busy class D airport on the north side of Phoenix. I need to establish 2-way communication before entering the class D airspace, which starts about 5 miles out from the airport.

What do I need to say? It’s pretty simple:

Who I’m talking to: Deer Valley Tower

Who I’m talking to: Deer Valley Tower- Who I am: helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima

- Where I am: eight miles northwest

- What I want: landing terminal helipad

- ATIS confirmation: with bravo

Ideally, this is the best formula, keeping things short. The initial radio call would be:

Deer Valley Tower, helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima is eight northwest landing terminal helipad with bravo.

But the information doesn’t have to be in that order. I could also say:

Deer Valley Tower, helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima is eight northwest with bravo, landing terminal helipad.

If I leave something out, there’s no reason to panic. The tower will ask for the missing information. So if I leave out the ATIS confirmation, they’ll say something like:

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, verify you have Information Bravo?

Or if I left out my position, they might say:

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, say position?

I’d reply with the missing information:

Affirmative, Zero-Mike-Lima has bravo.

Or:

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima is eight miles northwest.

Responding to ATC

When the tower responds to my initial call, all I need to do is repeat back the important part of the instructions. So if the tower says,

Helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima, Deer Valley Tower, report 1 mile north at or below two thousand. Plan midfield crossing at two thousand.

What’s important? RIght now, just to acknowledge that I’ve heard the instructions and will report again a mile north. So I’d say,

Zero-Mike-Lima will report one north.

Done.

I might also include mention of that altitude restriction, but I usually don’t. Why? Because the tower usually repeats it when they clear me to cross the runway. (The helipads are south of the two runways.) So they might say

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, Deer Valley Tower, we have you in sight. Cross both runways midfield at two thousand feet. Landing at the terminal helipad will be at your own risk.

I’d respond:

Zero-Mike-Lima crossing at two thousand.

I don’t have to repeat the risk thing. It’s the altitude restriction that they want to hear.

Note that in my original response, I chopped Six-Three off my call sign. Although a lot of the pilot reference material says not to do this until the tower does, I have never had a problem abbreviating my call sign before ATC does.

If ATC Makes a Mistake

Sadly, its pretty common for the tower to get my N-number wrong. I can’t tell you how often they think I said “Helicopter Six-Zero-Three-Mike-Lima.” They’d respond:

Helicopter Six-Zero-Three-Mike-Lima, Deer Valley Tower, report 1 mile north at or below two thousand. Plan midfield crossing at two thousand.

If they do that, my response to them corrects them using the entire N-number again, with stress on the scrambled characters:

Helicopter Six-THREE-ZERO-Mike-Lima will report one mile north.

In which case they repeat back the N number to correct themselves; no response is necessary.

If You Make a Mistake

I can’t tell you how many times I told a tower I was X miles east when I was really X miles west. Or X miles southwest when I was really X miles southeast. It happens. It’s dumb and sloppy, but it happens. It’s not the end of the world.

If you make a mistake and it’s something you think the tower needs to know, get back on the radio and correct yourself:

Sorry, Tower, Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima is really eight northEAST.

I usually put the stress on the word(s) that correct what I got wrong the first time. The tower will repeat it back and you don’t need to respond unless you get new instructions.

You don’t have to tell the tower about every single mistake you make. Maybe you told the tower you were 12 miles out and you’re really only 11. Not a big deal. Direction is far more important so the tower knows what direction they should be looking for you.

Leaving Out Your N-Number

It’s very important to include your N-number — either the whole thing or the abbreviated version — in every communication with a tower. I recently heard an exchange between a tower and a pilot who neglected to mention his N-number. The tower basically ignored him for two or three calls, then chewed him out over the radio. How embarrassing.

The tower was right, though. If you don’t give your N-number, the tower doesn’t know who’s talking. How can it answer and provide instructions?

I’ll be the first to admit that I occasionally omit my N-Number when I’m having a “conversation” with a tower. For example, if a tower asks a direct question:

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, confirm you have information Bravo.

I might answer:

That’s affirmative.

It’s also wrong. The only reason I get away with it is because (1) I immediately answered a question directed to me and (2) I am likely the only female pilot flying a helicopter in that airspace at that moment. It’s simple voice recognition on the part of the controller. But he has every right to demand I answer properly and I have no right to expect him to distinguish my voice from anyone else’s.

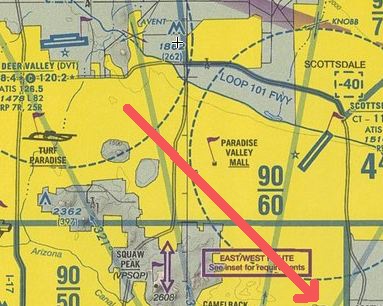

Requesting a Frequency Change

In the Phoenix area, there’s less than a mile between the Deer Valley class D airspace and the Scottsdale class D airspace. The towers know this, of course, so if you’re flying from one to the other, they usually give you a frequency change when you’re less than three miles from the airport you’re leaving. Even if you didn’t ask for it, they’ll say something like:

In the Phoenix area, there’s less than a mile between the Deer Valley class D airspace and the Scottsdale class D airspace. The towers know this, of course, so if you’re flying from one to the other, they usually give you a frequency change when you’re less than three miles from the airport you’re leaving. Even if you didn’t ask for it, they’ll say something like:

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, frequency change approved.

But sometimes they don’t cut you loose. Maybe they forgot. Maybe they’re busy. Maybe there’s traffic in your area and they want to be able to talk to you. Who knows? It doesn’t really matter. It’s pretty handy to get an early frequency change so you can listen to the ATIS and prepare for your radio call to the next tower.

To ask for it, just say:

Deer Valley Tower, Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima requests frequency change.

The response will likely be:

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, frequency change approved. Good day.

You can now change the radio frequency while still in their airspace.

Transitioning

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve avoided airspace just so I didn’t have to talk to a controller. I don’t do that anymore. Transitioning through the edge of a class D or C or even B surface airspace is easy. Just remember the formula:

Who I’m talking to: Scottsdale Tower

Who I’m talking to: Scottsdale Tower- Who I am: helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima

- Where I am: six miles west

- What I want: transition southeast through the southwest side of the airspace

- ATIS confirmation: with bravo

So the call might be:

Scottsdale Tower, helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima is six miles west with bravo. I’d like to transition southeast through the southwest side of your airspace.

If you don’t mention the ATIS, no big deal. You’re not landing there, so you don’t need it. Chances are, they’ll give you the current altimeter setting anyway. They might say something like this:

Helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima, Scottsdale Tower, proceed as requested. Scottsdale altimeter two-niner-niner-seven.

I usually respond with something like,

Two-niner-niner-seven, Zero-Mike-Lima.

Or sometimes I just repeat my abbreviated N-number to acknowledge that I heard them. That’s it. When I’m clear of the airspace, if the tower frequency isn’t busy, I’ll say something like,

Scottsdale tower, helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima is clear to the south.

Otherwise, I don’t bother.

Unusual Requests

Once in a while, you might have an unusual request — something beyond simply coming or going or transitioning. I had one of these a few weeks ago.

A client wanted a custom tour of the Phoenix area that included circling five different addresses. When I plotted the addresses on SkyVector to create a flight plan, I realized that I’d be passing through and circling within Phoenix Sky Harbor class B and Chandler class D airspaces. The flight required me to talk to Glendale tower on departure, Phoenix tower on transition, Chandler tower for operation in the northeast corner of their airspace, Phoenix tower again for operation in their surface area before another transition, and back to Glendale tower for landing. All within about an hour.

Even though I’m pretty confident these days about my radio communication skills, I admit that I was nervous about this one — especially since most of the addresses we needed to circle were in subdivisions filled with lots of homes that look nearly identical from the air. I didn’t want my client disappointed, so navigation was a huge issue.

What is it they say about pilot priorities? Aviate, navigate, communicate. Of the three, the flying would be the easiest part!

Amazingly, this came off without a hitch. Why? Because I remembered the primarily goal of radio communication: to communicate what you need. So, for example, when I was still 10 miles out from Chandler, I said something like:

Chandler Tower, Helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima is ten miles northwest. We need to take some aerial photos of three targets in the northwest corner of your space. The closest to the airport is at Route 202 and Alma School.

The tower came back with:

Helicopter Zero Mike Lima, Chandler Tower. What altitude do you need?

Duh. I should have mentioned the altitude. But no big deal, huh? The tower just asked me for the information they needed. I replied:

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima will stay at or below two thousand feet.

To which they replied:

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, you can proceed as requested. Chandler altimeter is three-zero-one-one. Report on point.

What he did was give me permission to do the job but also to let him know when I was at each location I needed to circle. I replied with my abbreviated N-number to let him know I’d heard him. Then, when I got to the first address, I said:

Chandler Tower, Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima is on point at the first target.

To which he replied,

Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, thank you.

We repeated this exchange two more times. He also advised me of some traffic when I was at my second target; the traffic was at least 300 feet above me and not a factor. When I finished with the last target and departed to the north, I said:

Chandler Tower, helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima is clear to the north. Thanks for your help. Good day.

Although there was only one target in the Phoenix class B surface area, there was also another helicopter just outside the surface space, about a mile east of me, circling. The tower was busy with jets, but they also had to advise me of this traffic, which they saw on radar but weren’t talking to. Fortunately, I saw it both on my helicopter’s traffic information system (at my altitude!) and then visually. I was able to confirm that I would keep visual separation. We circled the site and departed to the north.

I like to think of this flight as my “final exam” in aviation communication. I passed.

Just Communicate

If you’re a pilot struggling with communication, relax. Magic words and phrases aren’t necessary. Just communicate. Tell the tower what you want. Believe me — they’ve heard it all. No matter how bad you think you are on the radio, there was someone worse only an hour ago.

Air traffic controllers are professionals. They deal with it. Do your best and you’ll do good enough.

And the more often you communicate while flying, the better you’ll get.

Who I’m talking to: Deer Valley Tower

Who I’m talking to: Deer Valley Tower In the Phoenix area, there’s less than a mile between the Deer Valley class D airspace and the Scottsdale class D airspace. The towers know this, of course, so if you’re flying from one to the other, they usually give you a frequency change when you’re less than three miles from the airport you’re leaving. Even if you didn’t ask for it, they’ll say something like:

In the Phoenix area, there’s less than a mile between the Deer Valley class D airspace and the Scottsdale class D airspace. The towers know this, of course, so if you’re flying from one to the other, they usually give you a frequency change when you’re less than three miles from the airport you’re leaving. Even if you didn’t ask for it, they’ll say something like: Who I’m talking to: Scottsdale Tower

Who I’m talking to: Scottsdale Tower

Here’s proof. I was distracted by a tweet that took me to Amazon.com and was further distracted by a “Lightning Deal” offer for the Garmin nüvi 500 GPS. Here’s the deal as it appeared on Amazon.

Here’s proof. I was distracted by a tweet that took me to Amazon.com and was further distracted by a “Lightning Deal” offer for the Garmin nüvi 500 GPS. Here’s the deal as it appeared on Amazon. What did I discover on

What did I discover on  And the deal isn’t so sweet when you look at Amazon’s regular (not “Lightning”) price: $232.38. Now you’re saving only $67 or 22% off retail price, despite the fact that Amazon claims you’re saving $267 or 54%.

And the deal isn’t so sweet when you look at Amazon’s regular (not “Lightning”) price: $232.38. Now you’re saving only $67 or 22% off retail price, despite the fact that Amazon claims you’re saving $267 or 54%.

Hold down the Control key and click right on the spot you want the coordinates for. A menu pops up. (You may be able to simply right click, but I’ve had limited success with that on my Mac using Firefox; Control-click always works.)

Hold down the Control key and click right on the spot you want the coordinates for. A menu pops up. (You may be able to simply right click, but I’ve had limited success with that on my Mac using Firefox; Control-click always works.) Above the map area, in the blue bar, click the Link button. A window appears with two text boxes in it. The contents of the top text box, which are selected, includes a link to the map that you might paste into an e-mail message. It also includes the GPS coordinates, which I’ve indicated with a red box around them. Sometimes the GPS coordinates are not so obvious and you’ll need to scroll through the contents of the box to find them.

Above the map area, in the blue bar, click the Link button. A window appears with two text boxes in it. The contents of the top text box, which are selected, includes a link to the map that you might paste into an e-mail message. It also includes the GPS coordinates, which I’ve indicated with a red box around them. Sometimes the GPS coordinates are not so obvious and you’ll need to scroll through the contents of the box to find them.