Santa drop-off, burgers with friends, and the special apple delivery.

I don’t care what the calendar says — winter is definitely upon the Wenatchee Valley where I live. After an early snowfall not long after Halloween and a subsequent thaw, the typical winter weather moved in, with four days out of seven filling the valley with fog. Sometimes my home, which sits about 800 feet above the river, was under it, other times it was in it, and a few times it was above it. The temperature hovered between 25 and 35 degrees day and night, so it wasn’t that cold. But it could be dreary, which is bad medicine for a sun-lover like me. I honestly don’t understand how people can live on the west side of the Cascades where it’s gloomy far more often than sunny all year around.

I normally go south for the winter and this year is no different. But I had some business to take care of at home, including my annual Santa flight, and couldn’t get back to the sun until after that. Scheduled for December 4, I fully expected it to be my last flight of the year. But sometimes I get lucky. Here’s a quick rundown of the three flights I finished the season with.

The Santa Flight

Pybus Public Market is a venue on the waterfront near downtown Wenatchee, WA. Once a steel mill, it was completely renovated about five years ago and now houses several restaurants and shops and hosts indoor and outdoor merchants for seasonal farmers markets and other events. It’s a really great public space, and a destination for locals and tourists, with plenty of events and things to do and see. Anyone who visits Wenatchee and doesn’t stop by Pybus is really missing something special.

Here I am with Santa in 2012. Penny came along on the flight — she loves to fly in the helicopter. Note the polo shirt I’m wearing. Even with Santa’s door off, I wasn’t cold in December in Phoenix.

When I lived in Arizona, I was one of several helicopter owners/operators who volunteered to fly Santa in to the Deer Valley Airport restaurant in north Phoenix. The restaurant — which I highly recommend if you’re in the area; get the gyro sandwich — was privately owned by a Greek family and one of their sons would don a Santa suit on Saturdays and Sundays. For the four weekends leading up to Christmas, he’d get flown in by one of the local helicopter operators where a crowd of parents and children waited and cheered his arrival. We’d take turns picking Santa up at one of the FBOs at the airport, flying him north out of the airspace, and then turning around and returning — so it looked like we were flying in from the North Pole — and landing in front of the crowd. Once inside, Santa would sit on a big chair and kids would sit on his lap and tell him what they wanted for Christmas while parent cameras snapped. Then, I assume, the whole family would stick around for lunch. I blogged about the first time I did this, back in 2011; my wasband came along and took photos and you can see them in the blog post.

So when I moved to the Wenatchee area and fell in love with Pybus, it made sense to offer up the helicopter for Santa’s big arrival the weekend after Thanksgiving. Usually, Santa arrived in a fire truck, but most people agreed a helicopter would be way more exciting. I worked with Steve, the manager there, and set up a safe landing zone — or “heliport,” if you go by the definition that the county illogically clings to (long idiotic story there) — at the south end of the building. I picked up Santa at the airport and flew him in while a small crowd looked on. That was in 2013, the year I bought property for my new home in Malaga.

In subsequent years, Santa and I repeated the performance with bigger crowds every year. Weather was usually a factor though, and I remember one year waiting until the last possible minute to decide whether the flight was a go or no-go. But we made it each year and, when the weather was bad, I departed as soon as the crowd was inside the building so I could get the helicopter put away before the weather closed in again.

In 2016 — last year — the helicopter was in Arizona for its mandatory overhaul so I couldn’t do the flight. There is another red helicopter based in Wenatchee, however, and I knew the owner. I asked him to do it and he was game. But the weather did not cooperate at all and he couldn’t make the flight. Santa arrived on a fire truck that year.

This year, however, the helicopter was back in Washington and ready to go. I watched the weather all week and found it hard to believe the forecast for Sunday was as good as it was. On Friday morning, I went with Steve to the local radio station and talked up the upcoming flight. Steve said some really nice things about me and the other person who’d come along for the radio spot. Afterwards, I suggested that if the weather was good, Steve and I would go down to Blustery’s in Vantage for lunch. Bring a friend or two, I suggested. I was in no hurry to put the helicopter away if the weather was going to be good.

When Sunday arrived, the weather was perfect for a flight: clear, no fog, light wind. I picked up Santa at Wenatchee Airport and we touched down in the parking area — “heliport”? — there right on time. Here’s a video of my arrival on the Wenatchee World’s Facebook page.

Here’s Santa stepping out of the helicopter at Pybus. I have a sneaking suspicion this Pybus website photo is from the 2015 flight because I don’t remember anyone being in the doorway when I arrived this year.

After Santa and most of the crowd went inside, I shut down the engine so a few of the onlookers could come closer to the helicopter. I gave the kids postcards that featured an air-to-air photo of the helicopter over a lake that could be along the Columbia River. Kids got their photos taken with the helicopter. I answered the usual questions about speed and fuel burn and how long it takes to become a pilot.

The helicopter at Pybus Public Market after last Sunday’s Santa flight. I like to give kids a chance to see the helicopter up close.

Will Fly for Food

Once the crowd around the helicopter broke up a little, we cleared the landing zone and Steve and a friend climbed on board. I started up and, a few moments later, took off over the river.

I cannot stress enough how perfect the weather was for flying. The cool air and recent engine overhaul worked together to give me amazing performance; cruising at 110 knots was easy. With very little wind, the flight was smooth and I could easily steer the helicopter anywhere I wanted to go. It was my first day flying in over six weeks and it really reminded me why I’d gotten “addicted” to flying and why I loved it so much. I felt as if I could have flown all day, stopping only when I needed fuel, and exploring every bit of the area that I loved.

We flew downriver over the two bridges and along the shoreline. I detoured to the south a bit to fly past my home, which Steve had never seen. Then we got back over the river and continued down toward our destination, about 30 miles (as the crow flies) away. It was nice flying with friends again — I haven’t been doing as many pleasure flights as I like these days — and seeing familiar terrain through their eyes. We saw the fire damage from the two early summer fires, one of which had come frighteningly close to where I live, new orchards and vineyards going in near Spanish Castle, and rock formations along the river. I dropped down low for a better look at the two huge herds of elk on West Bar, then flew up the Ancient Lakes side of Potholes Coulee and down the Dusty Lakes side. We went “backstage” at the Gorge Amphitheater, which was buttoned down for the winter, and past the Inn and yurts at Cave B Estate Winery. I flew past the rock climbers at Frenchman’s Coulee and pointed out the sand dunes near there that are virtually unknown to the folks in the area because they can’t be seen from any road.

Around then is when the wind picked up a little bit, adding some mild turbulence to the flight that made Steve a little nervous — unless he was just kidding? As I descended toward Vantage, I could see some whitecaps on the water surface below us. I crossed over the top of the I-90 bridge and made a right descending turn to my usual parking spot — or “heliport”? — at Blustery’s, crossing over the freeway just 100 feet up. As I set down — rather sloppily in a strong crosswind — I wondered if it was open because there was only one car there. But as I cooled down the engine for shutdown, we saw the OPEN sign. A few minutes later, we were inside, placing our orders.

Steve and his friend Annette with the helicopter at Blustery’s in Vantage, WA.

The folks who work in Blustery’s know me and always seem glad to see me. I know they know the helicopter is out there in the parking lot when I come, but none of them have ever said a word about it. One of these days, I’m going to take them up for a quick ride.

I ate my favorite three-meals-in-one-burger: the Logger Burger. It has two burger patties, bacon, ham, cheese, and a a fried egg. It’s huge and very tasty. And messy. I didn’t think I could finish it all, but I did. I pretty much skipped the fries. Steve picked up the tab, of course. That’s one of my rules: when I fly you for a meal on my dime, I fully expect you to pick up the tab for that meal. Folks who don’t get that, don’t get a second flight.

It was about 3 PM when we headed out on the return flight. The wind down there was still blowing pretty hard — it’s almost always windy on the river there — but I pointed the helicopter into the wind and let it help us climb out. I flew along the cliff face on the west side of the river, looking for the bighorn sheep I knew might be there. When I spotted one, I made a 360° turn to loop around and make sure my passengers could see it. It turned out that there were two of them, running off to the west with their white butts making them easy to see among the golden grass and sagebrush. We continued onward over the tops of the cliffs there, looking for more wildlife but coming up empty. This time of year, the elk move to lower elevations along the river, which is why we’d seen so many at West Bar, across the river from Crescent Bar. We descended closer to the river near the old Alcoa aluminum plant, where I made my radio call for landing at the airport. A short while later, we were on the ground.

I put the helicopter away, thinking it was the last time I’d fly it for the year.

The Apple Express

I was toiling over my to-do list at 7:30 AM on Tuesday when my phone rang. It was the helicopter pilot for one of my clients. I’d done such a good job flying them around a few years back that they’d decided they needed their own helicopter and had bought one. Tyson, a vet who’d learned to fly in the Army, had been hired to fly it and we’d become friends. I still flew for them occasionally, but not as often as I’d like to. They’re really nice folks and I always learn a lot about agriculture when we fly together.

Tyson’s helicopter was in pieces in Hillsboro, OR, for some scheduled maintenance. Normally, that was fine — his employers rarely flew in the colder months. But this morning, they had an emergency. They had to get 240 pounds of apples to a packing plant in Pasco, WA and had a tight deadline. Making the 2-1/2 hour drive was not going to get them there on time. They wanted to fly them. Could I take them on my helicopter?

After a miserable Monday, that day’s weather was perfect. There was some patchy fog low over the river here and there, but a quick check of the weather along my flight path showed it was good to go. So I said yes, got dressed, and hustled to get the helicopter ready for departure.

Tyson came with me, mostly because he knew the landing zone — “heliport”? — better than I did. We left Wenatchee Airport together and landed at the landing zone his employer had set up behind their facility in Wenatchee. On our descent, we spotted a bald eagle perched on a pole beside an empty osprey nest.

The boxes of apples filled the back seat area of the helicopter.

The apples were in 20-pound boxes and they absolutely filled the back seat area of the helicopter. Honestly, I didn’t think they’d all fit. But we got them in, closed the doors, strapped ourselves back in, and headed southeast on a direct course for the packing plant northwest of Pasco Airport, 86 nautical miles away. That meant an immediate climb to clear the cliffs just south of my home. I hadn’t flown that way in a long time; I prefer following the river whenever I can, but when a client is paying for flight time, you go direct whenever possible.

Just beyond the ridge, the valley was filled with low clouds. I maintained altitude as we flew over them, crossed the river again, and cut across the Quincy basin. The clouds disappeared. The air was calm and the flight was smooth. Tyson and I chatted about all kinds of things. It was nice to have company on the flight. We crossed Saddle Mountain and I maintained altitude to cross the Hanford Reserve, which has been in the news too much lately. The chart requests that pilots maintain 1800 feet MSL over that area and I’m all for that, especially since our flight path took us pretty darn close to the nuclear power plant at the south end of the reserve. The clouds were over the river there again and visibility at nearby Richland Airport was down to 1 mile. I exited the reserve area and started my descent, flying over those clouds.

I called in to Tri-Cities Airport for permission to land. Even though we weren’t landing at the airport, our landing zone was within Tri-Cities’ airspace so communication with the tower was required to enter the space. We saw the facility when were were still a few miles out and Tyson guided me to the landing zone on the southwest side, a gravel parking area. I flew low over some wires and set down smoothly in the middle of the area.

I was expecting someone to come out and receive the boxes, but no one appeared. So Tyson and I offloaded them ourselves, setting them out in a row on the gravel so my downwash on departure wouldn’t knock over a stack. Tyson walked off toward the building and found someone to talk to about the boxes while I took a few photos and secured the back doors. Then he climbed back on board and we departed to the northwest, after chatting with the Tri-Cities tower controller again.

Before departing, I took a photo of the helicopter in its landing zone with the apples we delivered. I have a lot of photos of my helicopter in various unusual landing zones. (Or do I mean “heliports”? I’ll have to ask the folks at the Chelan County building department, since they apparently know more about helicopters than I do .)

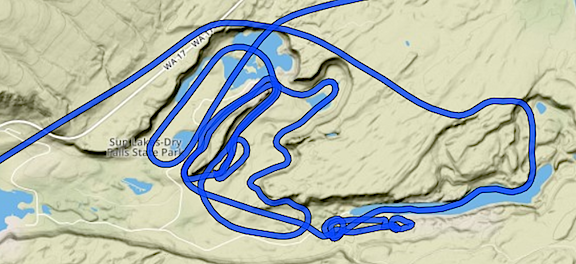

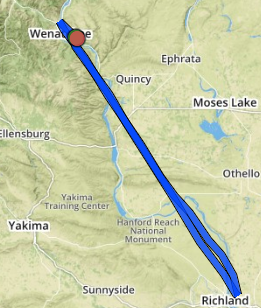

Our track log for the apple delivery flight. I use Foreflight to automatically track the exact path of all of my flights these days.

We returned by almost the same exact route, although I did pass on the west side of the nuclear power plant on my way back. By then, just about all of the low clouds had cleared. It was still calm and smooth. I flew much higher than I usually did, even after leaving the Hanford area, and was treated to unobstructed views of Mount Rainier and Mount Adams. The only other interesting thing we noted on the way back was a C-130 transport flying below our altitude on a practice run for a drop zone east of our flight path. Tyson knew the frequency they’d be talking on and we tuned in. Soon, we heard air traffic control notify the huge plane about traffic 10 miles west at 3300 feet northwest bound — us. Tyson and I kept an eye on it until we were well clear of the area.

I crossed the ridge behind my house again and started the steep descent to the airport. When I set down, I had mixed feelings. I was sad that this would definitely be my last flight of the year — I had meetings on Wednesday and was leaving town on Thursday — but happy that I’d gotten this unexpected flight on such a great day for flying.

One of my favorite clients,

One of my favorite clients,  There’s nothing quite like chasing trucks through the desert with a helicopter.

There’s nothing quite like chasing trucks through the desert with a helicopter.