More cherry drying stories.

I slept like crap last night. The wind was blowing hard and the awning of my camper was out, acting like a big sail. It caught the wind and tossed around the camper. Around 2 or 3 AM, it started drizzling just enough to make me wonder how hard it would rain. I dozed fitfully in all of this until around 4:30 AM, when the drizzle turned to a steady rainfall. It started getting light and I knew my phone would ring. I wanted to make sure I had some coffee in me before I had to go out.

I was contracted to dry cherry trees for three growers in the Quincy area. One grower had a “priority contract,” which meant he’d get dried first — if he called. He had 47 acres in Quincy and another 10 acres in East Wenatchee, a 10-minute flight away. The other two growers with their total of 27 acres would get dried afterwards in the order they called. And if I finished that, there was another 50 acres up for grabs in one 10-acre block and one 40-acre block.

My big worry was that I’d have to dry the 47 acres in Quincy, then shoot over to East Wenatchee to dry another 10 and shoot back before drying the 27 total acres belonging to the other two growers. I figured that with drying and travel time, I probably wouldn’t be able to get to that 27 acres for a good two hours after my start.

That was the worse case scenario. It’s also part of what kept me up last night — worries that I wouldn’t be able to provide prompt service to my growers. But, in my defense, the two non-primary growers knew what they were getting into when they signed the contract with me. They were paying considerably less in standby monies to be second and third on my list. They were willing to gamble; I’d just do my best to make everyone happy.

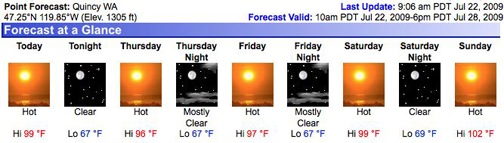

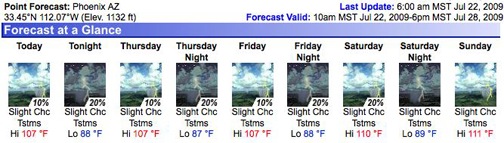

I thought about this as I made my coffee and fired up my computer to check the weather. I also thought about the other ways the drying flight could play out — ways that were better for all concerned.

I thought about this as I made my coffee and fired up my computer to check the weather. I also thought about the other ways the drying flight could play out — ways that were better for all concerned.

Radar showed a line of heavy rain moving west to east across the area. A big yellow blob was sitting right on top of my location at Quincy — which would explain the sound of heavy rain on the roof of my camper. The storm had already mostly passed through Wenatchee. I peeked out the window at the brightening sky and could clearly see where the storm front ended. Beyond it was clear sky. The wind had already died down.

I was sipping my coffee when the first call came. It was the orchard manager for a grower with 15 acres in Quincy. He was also the owner of the 10+40 additional acres that were at the bottom of the priority list. He told me it had stopped raining at the orchard and they needed me to dry. But they’d already picked most of the bings, so the only thing they needed drying in the main block was the sweethearts. He described where they were in relation to a house on the property. It was about 5 acres. When I was finished, I could do the 10 acres near his house. I told him I’d be at the orchard within 15 minutes and reminded him that his 10 acres needed to wait until I’d filled all the other requests. He understood.

I pulled on my flight suit and tank top. It was cold, so I zipped up securely. Then I grabbed my GPS, paperwork, and telephone and headed out the door. It had stopped raining by the time I got out of the truck at the helicopter and started pulling off the cover and tie-downs. It was already preflighted and fueled, but after putting the truck away, I did a good walk-around anyway.

That’s when the second call came. It was a grower with 12 acres in Quincy. I knew he’d started picking, and asked him where I should dry. He said that I may as well dry it all; the trees they’d picked were mixed in with the ones they hadn’t picked. He asked if the priority grower had called. “Not yet,” I said.

“Call me when you’re on your way,” he said. “I’ll have my wind machines running until you get here.”

They all knew that I wouldn’t start drying a block if wind machines were operating in it.

We said our goodbyes and hung up. Now I had two growers with 3 blocks in Quincy: 5 + 12 + 10 acres. The blocks were less than 2 minutes apart. This was looking good for everyone.

Unless the priority grower called.

The first orchard I dried today. The black border indicates the entire orchard block. The blue is the area I understood needed to be dried. The rest was apparently already picked.

I climbed on board and started the engine. While the engine warmed up, I hooked up my cell phone to the intercom system and pulled on my helmet. I punched in the waypoint identifier for the first orchard. A few minutes later, I was climbing out, heading northwest. Within 6 minutes, I was dropping back down at the first orchard, setting in to begin my drying runs.

This first orchard had mature trees of mostly uniform height. I settled down between the first two rows with my skids about 5 feet over the tops of the trees and flew at about 5 knots. I twisted my head around to see where my downwash was going — it was covering the trees nicely. There was no wind — at least not enough to bother me — and I had no trouble turning at the end of the row and coming up the next row.

On the ground, I could see workers waiting by some storage sheds and the road. No one signaled to me or called me, so I just ignored them and and kept working my way back and forth, up and down the rows. I was at it for about 15-20 minutes. Then I was done.

I lifted off and headed in the direction of the 12-acre block. I punched it into the GPS so I could zero in on it without having to waste time looking for it. I had it in sight when I remembered to call the grower. “I’m coming in,” I told him.

The second orchard block I dried today. You can see the pole for the wind machine in the middle of the block.

He had a wind machine running in the block and he hurried to shut it down. As I came down, I watched the pattern of the wind machine’s output on the tree tops. I chose the northwest (lower-left in the photo) corner of the block to begin. These trees were densely planted, but not quite as mature. I could tell from the start that going up every other aisle would throw enough air to dry them. The trouble was, the rows were so close together that I couldn’t always see the gap between them. That cleared up when I’d gotten about 10 rows into the orchard. Suddenly, there were long, white tarps in the empty space between the rows of trees. Well, most of them, anyway. It made it a lot easier to find where I needed to fly.

I was about halfway into it when my phone rang. It was the orchard manager, the guy with 10+40 more acres to dry. He wanted to know if the priority guy had called yet. I told him he hadn’t and that I’d do his 10 acres next.

“How about the North 40 block?” he asked. That was his 40 acres, which was about a 5 minute flight from where I was.

“If I don’t get any other calls, I can do that, too,” I said.

“What about the J and R block?”

He was referring to a 40-acre block owned by another grower. This other grower had another 40-acre block, bringing his cherry blocks to a total of 80 acres. I knew where they were and had their GPS coordinates. But I’d already warned him that I couldn’t take on that much more work. If he wanted those two blocks dried, he’d have to get on contract. I’d find him a pilot, and he’d have to pay standby costs. When I called and told him all this, he said he wasn’t interested. Now, true to form, he was trying to get drying service without being on contract. This really pissed me off and I wasn’t about to let him get away with it without paying a hefty premium.

“I spoke to him,” I said into my helmet’s microphone (and, hence, cellphone), “and told him he’d have to get on contract. He didn’t want to. If I have time, I can dry it, but he’ll have to pay more.” And then I quoted him a rate that was nearly three times what my contracted growers were paying. “It he wants to pay that,” I said, “let me know and I’ll go dry it.”

He told me he’d call back.

I finished up the orchard, being careful to avoid the wind machine tower and powerlines along the last row of trees. Then I pulled up and made the 60-second flight to the 10 acre block.

The third block I dried.

The wind machine was still running when I arrived. I stayed high and called the grower. After a bunch of rings, it went through to voicemail. I was leaving him a message when I saw someone speeding to the base of the wind machine on a quad. A moment later, the blades slowed and stopped.

This block had big, wide aisles between rows of youngish trees. I could easily dry them by flying over every other aisle. The only obstruction was the wind machine tower in his block and another tower in an adjacent block that might be a bit close to my tail rotor when I turned. When I got close, I flew sideways down the aisle until I knew I’d cleared it, then turned and continued, pointing in the direction I was flying. I was finished in less than a half hour.

The grower called again. He wanted to know if the primary grower had called. He still hadn’t. But I wasn’t about to head on out to the North 40 block until I’d spoken to him. We discussed this and hung up as I left the block and started flying towards North 40. I called the primary grower. He said he was on his way to the orchard, but his manager said he didn’t think his cherries needed drying. He’d let me know.

So I flew out to the North 40 block. It was quite a distance from town — a good 15-minute drive on dirt roads — and I don’t have a photo of it. It’s basically an 80-acre block of well-irrigated land with cherries on the north half, apples (I think) on the south half, and a line of windbreaker trees between them. There’s a mobile home on part of the cherry block’s land and a 5-foot fence around the whole block.

The trees are very young and very widely spaced. I could fly up every third aisle at about 8-10 miles per hour and still get them all covered. Because there were no obstructions, the work went quick. I was on one of the last passes when a deer ran out from a row of cherries. It was inside the fence. I made a note to myself to tell the grower.

Then I was done. I’d flown nearly 2 hours straight and had about 1/3 tanks fuel left. I decided to refuel and give the primary grower another call. It was a 6-minute flight back to my base where I shut down, pulled my helmet off, and went about the task of adding 15 gallons of fuel to the main tank. I wanted to have enough fuel on board in case the primary grower needed me to dry all his blocks. But when I called him, he confirmed that the trees were okay. He was worried about the cherries getting beat up more than necessary and decided to take his chances with the moisture on them. And in East Wenatchee, it had hardly rained at all.

I thought I was done, but then my phone rang again. It was the manager for the first orchard. He told me I’d forgotten to dry three rows of sweethearts on the west side of the wind machine. His description confused me. He’d originally told me the cherries were behind the house. It wasn’t until I was airborne over the orchard again that he called and directed me to the orange shaded area shown in the first photo here. I hadn’t “forgotten.” He hadn’t told me they needed drying. It was a shame because it took another 1/2 hour to start up, fly out there, dry it, and fly back. If I’d known about the rows from the start, I could have probably knocked them off in 1/10 or 2/10 hour.

The sun had broken through the clouds by the time I landed back at my base. I made a beeline back to my camper for a bathroom, change of clothes, and cup of coffee. Outside, it was shaping up to be a very nice day.

I was done flying for the day. I’d logged 2.5 hours. It was 8:35 AM.

Later in the day, I spoke to the owner of the second block I’d dried. He complemented me on my flying and said he liked my helicopter. He said I’d done a great job and that I’d arrived at his place faster than any other pilot he’d ever hired. Then he said what they all say: “I hope I don’t have to call you again this season!”

In the foreground, you can see the orchard’s upper reservoir. Farther down, beyond many cherry trees, is a smaller, algae-covered pond. There’s a parking area on the close side and you can see my trailer parked there. On the far side is a tiny, bright red speck. That’s my helicopter.

In the foreground, you can see the orchard’s upper reservoir. Farther down, beyond many cherry trees, is a smaller, algae-covered pond. There’s a parking area on the close side and you can see my trailer parked there. On the far side is a tiny, bright red speck. That’s my helicopter. The orchard is 86 acres in the hills. This GoogleMaps satellite image doesn’t clearly show the hilliness of the area. The two red outlines indicate the blocks of trees. There’s a small one to the southwest but most of the trees are in a series of blocks all bunched together around roads, buildings, and irrigation ponds on the sides of hills. This is not the easy rectangular blocks of uniformly sized trees I dried in Quincy. This would be more challenging. Not only would I have to come up with a dry pattern that was efficient, but I had to make sure I didn’t miss any of the blocks.

The orchard is 86 acres in the hills. This GoogleMaps satellite image doesn’t clearly show the hilliness of the area. The two red outlines indicate the blocks of trees. There’s a small one to the southwest but most of the trees are in a series of blocks all bunched together around roads, buildings, and irrigation ponds on the sides of hills. This is not the easy rectangular blocks of uniformly sized trees I dried in Quincy. This would be more challenging. Not only would I have to come up with a dry pattern that was efficient, but I had to make sure I didn’t miss any of the blocks.

I thought about this as I made my coffee and fired up my computer to check the weather. I also thought about the other ways the drying flight could play out — ways that were better for all concerned.

I thought about this as I made my coffee and fired up my computer to check the weather. I also thought about the other ways the drying flight could play out — ways that were better for all concerned.