Probably the busiest Fourth of July I’ve ever had.

These days, I’ve been challenging myself to keep busy. Downtime between jobs has been damaging in the past, causing depression, frustration, and weight gain. I began fighting back last summer and remain determined not to spend time sitting on my ass when there are better, more interesting things to do. And let’s face it — almost anything is better than sitting around on your ass, letting the days of your life just tick away like a clock with an aging battery that can’t be replaced.

I try to sketch out a rough plan for each day of my life. Sometimes I tweet what I’m tentatively planning. Sometimes I don’t. Having a rough idea of what I plan to do helps keep me focused. Stating it publicly makes me responsible for doing — or trying to do — it. But I always let things take their course when I can. After all, no plan is set in stone. Spontaneity is what makes live truly interesting.

Yesterday, July 4, I set a busy schedule for myself. But I did even more than I planned. (And boy, am I feeling it today!)

Ross Rounds

As the time on that tweet hints, I wake up very early nearly every morning. Although its great to get an early start on the day, there’s a limit to what you can do that early when stores are still closed and friends are still asleep.

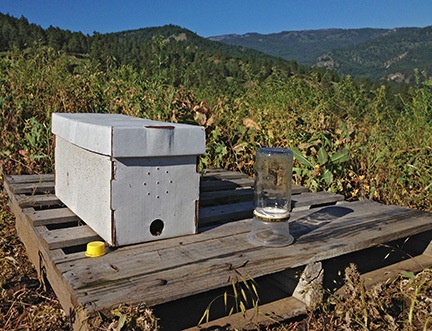

So while I sipped my morning coffee, I assembled my Ross Rounds.

Ross Rounds are a comb honey system that makes it possible for bees to produce packaged honey comb. You set up the special frames with plastic rings and pure beeswax foundation and insert the frames in their custom hive box. You then put the box on top of a honey-producing hive of bees. Eventually, the bees move into the Ross box and begin building and filling honeycomb in the special frames. When the rings are completely full of honeycomb and honey, you remove them, cover them, label them, and either sell them or present them as gifts to friends.

Here’s a fully assembled Ross Rounds frame.

Assembling the frames took some doing. I had to split each frame, lay in the ring halves and snap them into place, lay in a sheet of wax foundation, and snap the frame closed. The ring halves only go in a certain way, so much of the time was spent lining them up properly. But once I got the hang of it, the process went quickly. I got all 8 frames, with 4 pairs of rings each, done in about an hour.

I’m not sure when I’ll be able to use the Ross Rounds system. I’ve been told that because I started my bees so late in the season I probably won’t be able to take any honey from them. They’ll need all that they create now for winter. But I’ll do a hive inspection on my first hive — probably today — and see how much of their top hive box is full. If it’s more than 80% full, I’ll add a queen excluder and the Ross Rounds frame and see how far I get by the end of the season.

Motorcycle Ride

Meanwhile, I was texting back and forth with another early riser, my friend Brian, who lives in Wenatchee. He’d seen my plan for the day on Facebook and was wondering if I wanted company for my motorcycle ride. After some texting back and forth and a call to my friend in Chelan — who I woke at 8 AM! — we decided to ride up to Silver Falls together and do a hike before going our separate ways for the day.

Here’s Penny in her dog kennel on the back of my motorcycle. (Yes, she fits fine in there and can move around freely.)

Penny the Tiny Dog and I were at Brian’s apartment at 9 AM. Penny rides with me on the motorcycle. I bungee-netted her hard-sided dog carrier to my motorcycle’s little luggage rack. It’s rock solid there. She rides in the dog carrier behind me. I don’t think she actually likes the ride, but I do know that she likes coming with me wherever I go. So when I lift her up onto the motorcycle’s luggage, she scrambles into her carrier without protest.

What’s weird is when we stop at a traffic light and she barks at other dogs she sees.

Brian rides a cruiser — my Seca II is more of a sport bike — and he led the way, keeping a good pace. We made the turnoff at the Entiat River about 15 minutes after leaving his place. We both thought Silver Falls was about 12 miles up the river, but a sign about a mile up the road said that it was 30 miles. I saw Brian look at his watch as we rode past the sign. He had a BBQ to go to that began in early afternoon; I had other plans, too. But we kept going. We’d make it a short hike.

I really enjoy riding my motorcycle in Washington State. This road, which wound along the banks of a rushing river, reminded me of the riding I’d done in New York State years before: mountains, farmland, trees, and cool, fresh air. I think one of the reasons I stopped riding motorcycles when I moved to Arizona is because it was simply not pleasant. Too much straight and flat and hot and dry. The road up to Silver Falls is full of curves and gentle hills, with orchards and hay fields forests along the way. Every twist in the road brings a new vista in the granite-studded canyon. Every mile brings a different sensation for the senses that are switched off inside a car: the feel of temperature and humidity changes, the smell of fresh-cut hay or horse manure or pine. This is part of what makes motorcycling special.

We arrived at the parking area, which had only one car. It was just after 10 AM. I got Penny out of her box and on her leash. We stripped off our riding gear and started the hike.

Silver Falls

This was my second trip to Silver Falls. My first was back in 2011, not long after I had my motorcycle shipped from Arizona to Washington. I blogged about that trip here. And, if you’re interested, you can read more about Silver Falls on the Washington Trails Association website.

Here’s Brian alongside the creek. Penny refused to pose with him.

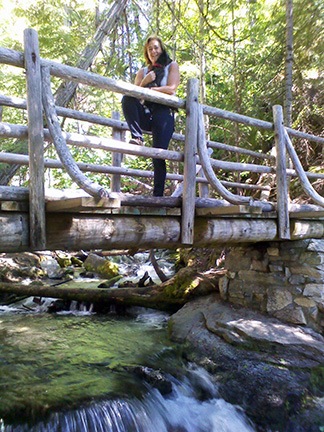

Brian shot this photo of Penny and me on the bridge near the top of the falls.

The three of us — Brian, Penny, and I — headed up the trail together, stopping now and then to take photos. The stream was rushing wildly, with crystal clear water cascading over rocks and logs in the stream bed. We followed the same path I’d followed on my first trip there, taking the trail on the right up to the top of the falls and coming back the other side. The temperature was perfect — a bit cool in the shade but nice and warm on the wide switchbacks in the sun. Brian led at a fast pace and I did okay keeping up. I remembered my first trip there when I was still a fatty and how long the hike up to the top had taken. What a difference 45 pounds makes!

We ran into some other hikers on their way up the other side as we headed down. Because of time constraints, we only spent about an hour and a quarter there. It was 11:15 AM when we geared up and headed out.

Because we were going our separate ways and I was running late to meet my friends in Chelan, Brian let me lead the way with the understanding that I’d go at my own pace. I let it rip and covered the 30 miles in 30 minutes.

Blueberry Hills

It was 11:45 when I reached the junction of Entiat Road and Route 97A. I had a choice: continue with my plan to visit friends in Chelan or head back to Wenatchee Heights and take it easy for a while before heading out to the BBQ that afternoon.

I turned left toward Chelan.

There were a lot of cars on the road, but they kept at a good speed just over the speed limit. I fell into place behind them. It was a lot warmer back on the main road, but not too warm for my denim jacket. The road left the river, passed through a tunnel, and climbed into the mountains. It crested and started down, with beautiful Lake Chelan spread out before me: blue water surrounded by green orchards and vineyards capped by a perfectly clear blue sky.

I pulled over in town to get my friend Jim on the phone. He and his wife Teresa agreed to meet me at Blueberry Hills, a you-pick blueberry place and restaurant in Manson. Penny and I stopped for gas along the way. We wound up behind Jim and Teresa’s car as they pulled into the Blueberry Hills parking lot.

They had their dog, Zeus, a red heeler puppy with them. Penny and Zeus became friends months ago when we were in California on a frost contract with the helicopter. Zeus was much smaller then. He’s getting close to full grown now and is a lot bigger than Penny. They looked genuinely glad to see each other.

We climbed the stairs to the outside patio overlooking the blueberry fields. Jim and I went in to order lunch. I bought the dogs a pair of frozen beef bones, which the restaurant sells for their four-legged customers. Penny and Zeus got right down to business. When our food came, so did we. Blueberry Hills makes excellent food.

We talked about all kinds of things while waiting for our food and then eating. Teresa had just come back from a visit to their daughter’s family in Anchorage. Jim, like me, was just recovering from a hectic week of cherry drying. We had stories to swap and insights to share. It was a pleasant lunch — one I wish I could have lingered over, perhaps with a piece of pie. But it was getting late and I was supposed to be at a friend’s house in Wenatchee at 3:30. So we headed out, stopping to pick up two pounds of blueberries along the way.

I took the road on the east side of the river on the way back to avoid the traffic in Chelan, Entiat, and Wenatchee. It was a quick 50-mile ride to the south bridges between East Wenatchee and Wenatchee. Two more traffic lights and I was winding my way up Squilchuck Canyon, back to my temporary home in Wenatchee Heights.

The Teachers’ BBQ

By the time I got into the Mobile Mansion, it was 3:26 PM. I texted Kriss, who I was supposed to meet in 4 minutes to let her know I’d need at least an hour. That was fine; we weren’t due at the BBQ until 5 PM anyway.

I cleaned up, dressed, and threw the blueberries into a cooler bag. I still needed to get the other ingredients for what I planned to bring to the BBQ: strawberries, whipped cream, and cake. But when I got down to Safeway, there wasn’t a single strawberry in the store. I wound up with a single package — the last one! — of raspberries. And frozen whipped topping. I did get a good deal on a July 4 themed serving plate, which I’d leave behind with my hostess.

At Kriss and Jim’s house, I assembled my fruit and cream and put it in the serving dish. Kriss gave me some red sprinkles to dress it up. I was disappointed at myself for not bringing something better. (I’m really looking forward to having a full kitchen again.)

I met Kriss and Jim’s daughter and husband. I gave Jim the nuc box and frame holder I’d gotten as a little gift for him. (I met them through beekeeping; Jim has four hives and has been going out catching swarms lately. My first bee hive is in their backyard until I close on my Malaga property later this summer.) I watched at their three kittens, two of which are just staying with them temporarily. I unwound from the frantic pace I’d been keeping all morning.

We all headed out to a friend’s home about a mile away. It was an annual July 4 BBQ where Kriss’s fellow teachers — some still teaching, others retired — gathered for burgers, grilled salmon, excellent sides, and dessert. I met a lot of new people and answered a lot of questions about my cherry drying and other flying work.

The BBQ wound up after 7:30 PM. I said my thanks and goodbyes and climbed back into my truck. I was exhausted from my day out and stuffed from a good meal. I wanted to go see the fireworks but had no desire to deal with the traffic. A nice evening back home might be a good end to the day…

The Spoons Party

But I passed right by another friend’s house on my way home. Shawn and his wife were hosting the BBQ that Brian had gone to. I’d been invited but had turned it down to attend the other BBQ with Kriss and Jim. Was the party still going on?

I drove past and discovered that it was. I parked and walked around back to see what was going on. My rafting friends — as I’d begun to think of them — were playing a card came I’d heard about on my last rafting trip with them. It involved collecting four of a kind and grabbing a spoon off the table. There were five players and four spoons. The person who didn’t get a spoon lost.

A silly game, but nonetheless, I pulled up a chair and another spoon was added to the table. I didn’t play very well at first, but got slightly better. The vodka may have helped.

This party had kids — four of them — and later had fireworks out on the street. The whole area, in fact, was full of fireworks. Fireworks are legal in Washington — at least this part of Washington — and were readily available all over the place. Shawn and Brian had bought a bunch. When it got dark enough to enjoy them, they put on a show out in the street. Family fun.

When they broke up and headed back to the backyard, I took my leave. It was about 10 PM and I’d had enough for one day.

I arrived around 4 PM, when the temperature was around 70°F. A nice warm afternoon when many of the bees would be out foraging. I brought my gear into what I’ve come to think of as the “bee yard” and was happy to see bees coming and going through the hive entrance. I saw Jim and Kriss and Jim came in to keep me company. I lighted the smoker and suited up. Jim remained in plainclothes, but stood back as I got to work.

I arrived around 4 PM, when the temperature was around 70°F. A nice warm afternoon when many of the bees would be out foraging. I brought my gear into what I’ve come to think of as the “bee yard” and was happy to see bees coming and going through the hive entrance. I saw Jim and Kriss and Jim came in to keep me company. I lighted the smoker and suited up. Jim remained in plainclothes, but stood back as I got to work.