An update on my wire-wrapped jewelry endeavors.

By now, the folks who know me well know that my jewelry making hobby has blown up into something resembling an addiction. Indeed, it’s difficult for me to pass up a shop or website that offers gemstone cabochons (cabs, to those of us who work with these things) for sale without taking a look — and likely buying ones within my budget. I’ve now got a collection of about 4 dozen cabs in various shapes and sizes made of a stunning selection of stones. They’re almost all polished to a reflective shine. Just gorgeous.

The weird thing about this is that I’ve been going to Quartzsite, AZ where I bought about half the cabs I have now, for more than 20 years and saw cabs for sale every single year. It wasn’t until I realized what I could do with them that I began buying them. And when I started getting kind of good at turning them into jewelry, the draw became irresistible. I’ve since found a good supplier on Easy who sells decent quality stones at a reasonable price. I’ve bought two dozen from them in the past two weeks.

More about Cabochons

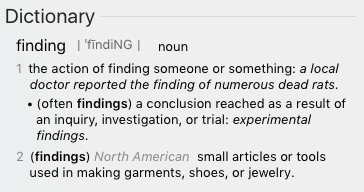

A cabochon, in case you’re wondering, is:

a gemstone which has been shaped and polished as opposed to faceted. The resulting form is usually a convex (rounded) obverse with a flat reverse.

Nevada Dendritic Sage Agate wrapped in sterling silver. I don’t think you can make a bad piece of jewelry out of such a nice stone — if you let the stone show.

Lapidaries create cabs by cutting stones into slabs, then cutting those slabs into shapes and polishing them with wheels of varying grits. I’ve seen guys do this and it looks like a ton of work. A good lapidary can produce beautiful cabs by finding the best features in a slab and featuring them in a finished cab. Those are the cabs I look for when I’m shopping.

Cabs range in size from very small — maybe 10 mm long — to quite large — over 50 mm on a side. I prefer them 30 to 45 mm long and 15 to 30 mm wide. Smaller than that and they’re tough to work with; larger and they make heavier pieces than I like.

Although I do like working with odd-shaped pieces, it’s a bit more challenging to get them properly wrapped. My skills aren’t quite reliable enough yet to tackle them successfully. So I stick with ovals, teardrops, and elongated pieces. I’m just starting to get the hang of dealing with square corners.

Turning Cabochons into Jewelry

There are basically three ways to turn a cab into a piece of jewelry:

- Drill a hole in it and use that to secure a finding or beading string. Drilling a hole in a stone basically turns it into a bead. I don’t do this. I don’t like the idea of drilling into a beautiful stone or using a hole to secure it in jewelry. That’s my opinion. I’m sure a lot of beaders would disagree. Sorry. (I should add here that when working with very small stones, I think beading is the way to go. I may use gemstone beads as accents in future pieces; I’m still thinking about it.)

- Use wire wrapping to secure the stone into the jewelry piece. This is what I do. There are several styles of wire-wrapping; the style I use is rather intricate, although I have experimented with simpler styles. I usually use 20 to 22 gauge square or round wire wrapped with 22 gauge half-round wire to create a custom frame for a stone, build a bail, and secure the stone into the frame. Then I use the excess frame wire to create accents with loops and swirls.

- Cut and solder metal to create jewelry mounts for stones. This is another nice way to turn a cab into jewelry — especially if the cab’s reverse side is marred or unfinished. This is both harder and easier than wire-wrapping. It’s harder because you need good metal cutting and soldering skills. But, in a way, it’s also easier because you can work with virtually any size or shape cabochon and get good results.

I’ve begun work on a blog post providing more detail on how I make my pieces. The only thing I need to finish it are step-by-step photos. It won’t be enough to teach you how to do it, but at least you’ll see what I do. There are some good videos on YouTube to get you started if you want to try and I’ll link to the ones I think are best in that blog post.

The Metals

This is K2 Granite — yes, from the mountain K2 — wrapped in sterling silver. The colored specs are natural. I’d score this a 5 out of 5; it’s currently my favorite piece.

Lately, I’ve been working almost exclusively with sterling silver, although I have worked with copper and silver plate in the past. (When getting started, it’s a good idea to work with cheaper metals.) My friend Dorothy sat down with me when we were both in Quartzsite in January and showed me how she makes her jewelry. That was the first time I worked with sterling silver. She stressed the importance of tight, even wraps and put me on the right track in a search for perfection. Every time I finish a piece, I give it an objective score of 1 to 5, with 5 being the best. I’m always shooting for 5s but am happy with 4s. I learn a lot from 3s and usually disassemble anything that scores lower than that.

Dorothy also taught me to save every single bit of silver that gets cut away from the piece. When my little plastic container is full, I can send it back to the silver supplier for credit on the purchase of more silver. At $16.60 per ounce (today’s price), those trimmings can really add up.

My Progress

I’ve come a long way since I started creating wire-wrapped gemstone cabochon pendants back in January. In fact, I look at some of the pieces I created back then, remembering how proud I was of them, and cringe.

My first pieces, prepped for sale. I’ll be selling these for just $10 each — a fraction of what I charge for my later pieces.

Why cringe? Well, most of them are terribly crude and generally immature. All those swirls — what was I thinking? This is the kind of jewelry a teenager would wear. That’s okay, but I’m not interested in making jewelry for teenagers.

Now compare those pieces to my most recent work here (and in closeups above):

Here are some of the pieces I created in the past week, all tagged and ready for packaging for sale. They range in price from about $40 to $50 each and are sold on a leather necklace with a hand-formed clasp.

If you like videos, try this one. It’s a show and tell for four recent pieces. (I really need to get a better setup for future videos.)

I think these designs are more finished looking and mature. (Maybe it’s just a matter of taste, though.) Not only am I using better cabochons, but I’m also wrapping them with sterling silver, although I haven’t completely given up on copper yet.

And yes, I am selling them. There’s a website where new pieces appear as they are finished: www.MLJewelryDesigns.com. There are links there to an online store. Selling them makes me happy and sad. Happy because other folks value what I do but sad because I hate to see them go.

I’ll also be at a kiosk/table at Pybus Public Market on three upcoming Saturdays, including this Saturday, March 31. I figure I’ll sit there for the day and make new pieces — maybe even some custom ones from unwrapped cabochons I’ll have on display and for sale. If you’re around, I hope you’ll stop by.

But if you’re not in the area, please do visit my online store and treat yourself or a loved one to a unique gift. I sure could use a cash inflow to feed my hobby with stones and silver wire!