A look back at the evolution of writing for publication.

Yesterday, my 72nd printed book went to the printer. For the first time ever, not a single sheet of paper was printed, mailed, or marked up during the writing and editing process for one of my books.

I’ve been a freelance writer since 1990. Most of my work — all of my books and 95% of my articles — has been about using computers. Yet for the first few years I wrote books about using computers, the manuscript files I created weren’t even used for the production of the book.

In the “Old Days”…

Back in the old days, my manuscripts had to be submitted in standard manuscript format. That means I wrote them in Microsoft Works (in the beginning) or Word using a plain font like Courier with double-spacing. What came out of my [$2,000] laser printer printer was a document that looked as if it had been typed on a typewriter by a very careful typist. Hundreds of pages. I was required to submit two printed copies of the manuscript to my editor.

In those days, Staples sold “manuscript boxes.” These were cardboard boxes designed to hold stacks of paper that were 8-1/2 x 11 inches. I’d print two copies of the manuscript, stack them one atop the other in this manuscript box, and mail them to my editor.

One time, in order to make a deadline, I sent the manuscript copies to Manhattan with my next door neighbor, who worked there. She then called a courier company to deliver the manuscript to the publisher’s offices in the Columbus Circle area.

In all honesty, I can’t remember how edits were handled. I don’t even recall getting any marked up copies of that early work. I think I got the galleys, though. They were printed (of course) and I wasn’t allowed to make many changes to them.

The Rise of E-Mail

Around the time of my fourth book (third solo book) in 1992 or 1993, e-mail was starting to get big. I still recall my shock and surprise when I sent an e-mail message to someone and got a response within an hour. Whoa!

That’s the book I started sending manuscript chapters via e-mail to my editor. The idea was that she’d review the chapters as they came in. This really saved my ass when my hard disk crashed and I lost everything on it. I was able to recover all those files from my editor and keep working. But when it came time to final submission, it had to be printed and mailed in: 2 copies, double-spaced.

This is one of the few books I wrote and laid out using FrameMaker. Its cross-referencing tools couldn’t be beat back in 1998.

When I started writing Visual QuickStart Guides for Peachpit Press in 1995, I also began doing layout. In the beginning, I used QuarkXPress, but I soon switched to PageMaker and finally to InDesign. I did a number of other books for Peachpit and for AP Professional (Claris Press, FileMaker Press) using FrameMaker, which I still think was the best layout tool out there. (InDesign is getting closer; thank heaven it finally added cross-referencing tools in CS4.)

For the early books, I’d create the chapter files, print them out, and mail them to my editor. Marked up copies would be FedExed back. I’d make the changes in the files. When the project was done, I’d send them a Zip disk or, later, burn a CD on my [$700] CD burner with all the files. That disk would travel by mail or FedEx on top of a stack of printed pages. In the beginning, they wanted 2 copies, but later they began using their own copier to make the copies they needed.

Word Files from Templates

This was the first book I wrote that made extensive use of Word templates.

Time went on. For the books I didn’t lay out, Microsoft Word became the standard. At first, I submitted files with the usual double-spaced, plain vanilla formatting. But some of my publishers got fancy and started sending templates with styles and macros and buttons built in. Although these files were always created on a Windows PC, they worked fine on my Mac. They usually came with detailed instructions for use; by applying the styles and submitting the files, my formatting would ease the task of getting it typeset on their system. Some of my publishers had terribly antiquated systems that required a lot of effort on the part of the production staff.

The use of Microsoft Word meant that my manuscript could go through a series of editors — copy, technical, and proofreader — with all edits clearly identified using the revision feature. I’d get edits back, review them, and either accept or reject them. Then I’d send them on to the next editor. The process was long and tedious, with lots of editing and a manuscript file that looked like a colorful mess of type. Often one editor’s changes would be changed back by another editor. Whatever.

I was required to send printed manuscript pages for most of the 1990s, but the files were transferred by e-mail, with a backup copy of all files on CD sent along with the printouts. I also got all galleys printed. That was often a lot of paper — hundreds of pages. In the mid 2000s, I started bringing the one-sided pages to my local copy shop to have them cut and padded; I’d use the back side of each page as scratch paper.

The Rise of PDFs

In the mid 2000s, I started seeing galleys as PDFs. I’d review them onscreen — no easy task when you have a smallish monitor and can’t read an entire page at once — then print out the pages with problems, mark them up, and send them into my editor. One of the reasons I bought a 20″ monitor a while back was to be able to proofread page by page.

Around the same time, Peachpit wanted to send me markups of my laid out book pages as PDFs. I resisted for quite a while because reviewing edits and making changes to the laid out page files with just one monitor was such a pain in the ass. My office now has a pair of 24″ monitors connected to one computer so I can review corrections on one screen while making corrections to manuscript pages on the other.

The End of Paper

The book I finished yesterday (Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard: Visual QuickStart Guide) was the first one that had absolutely no exchange of paper. I’d create book pages using InDesign and turn chapters into PDFs. I’d upload the PDFs and a zipped folder full of chapter files to Peachpit’s secure and private FTP server. The chapter files were my offsite backup — I did all of my work on this book from a camper or hotel and did not have a spare hard drive to back up to. My production and tech/copy editor would review the PDFs, mark them up with Acrobat — they use the full version, which I don’t have — and put them in a different folder on the FTP site. I’d download them, review them, and make manuscript page changes. Then I’d upload new PDFs to yet another folder and send fresh zipped files. My indexer got her own set of PDFs with accurate page numbers as we finalized pagination from one chapter to the next. When all editing was done, I updated the InDesign book file and its individual chapter files to finalize cross-references. (This is also the first Visual QuickStart Guide I’ve written that has cross-references to actual book pages rather than chapters.) I generated my table of contents and laid out the index when it arrived from my Indexer yesterday morning. Although I was still handling edits on Wednesday morning, by 10 AM yesterday (the next day), my editors at Peachpit had all the final files. By 5 PM the same day, the printer had those files.

I expect to see printed books within 3 weeks.

There are a lot of folks who see printed books as a terrible waste of paper. Although print publishing is definitely on the decline, there are many people — myself included — who prefer reference work in printed format. I don’t think print publishing will ever completely die.

I’m very pleased, however, that the production process didn’t add any more paper waste to landfills or recycling centers. I, for one, don’t need any more scratchpads.

Anyway, I thought some writers out there might be interested in the evolution of the writing/production process as seen by an “old timer” like me.

I’m just glad I never had to use a typewriter for my writing work. Using one in college was bad enough.

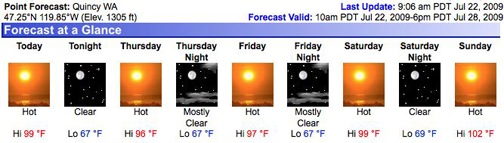

The orchard is 86 acres in the hills. This GoogleMaps satellite image doesn’t clearly show the hilliness of the area. The two red outlines indicate the blocks of trees. There’s a small one to the southwest but most of the trees are in a series of blocks all bunched together around roads, buildings, and irrigation ponds on the sides of hills. This is not the easy rectangular blocks of uniformly sized trees I dried in Quincy. This would be more challenging. Not only would I have to come up with a dry pattern that was efficient, but I had to make sure I didn’t miss any of the blocks.

The orchard is 86 acres in the hills. This GoogleMaps satellite image doesn’t clearly show the hilliness of the area. The two red outlines indicate the blocks of trees. There’s a small one to the southwest but most of the trees are in a series of blocks all bunched together around roads, buildings, and irrigation ponds on the sides of hills. This is not the easy rectangular blocks of uniformly sized trees I dried in Quincy. This would be more challenging. Not only would I have to come up with a dry pattern that was efficient, but I had to make sure I didn’t miss any of the blocks.