I’m tired of being criticized for being civil — and you should be, too.

I was at an impromptu neighborhood gathering the other day.

Most of the people in the group were thinking people who understand the difference between right and wrong and the importance of having a civil society where we work together to make the country a better place for all of us. But one couple among us had many of the ideas espoused by Fox News and other right-wing media: that the country’s problems can be blamed on high taxes, handouts to poor people, and, of course, immigrants. Since they were hosting the gathering (in an offhand way that really doesn’t matter for this discussion) the rest of us were walking on eggshells, afraid to say anything that would “set them off.”

You can probably guess how each of us feel about Trump being president. And if you’re not a Trump supporter but are friends with or related to people who are, I’m sure you know exactly what I mean about “setting them off.” These days, it’s difficult to maintain a friendship with people in the opposite camp any time politics comes up. Simply said, those who don’t support Trump think Trump supporters are either stupid, gullible, racist, greedy, or crazy. Or a combination of some of those things. I suspect Trump supporters think Trump detractors are just plain dumb.

It’s unfortunate that we have to go through the exercise of a Trump presidency for history to report which group was correct.

Slurs from our Childhood

Public domain image of Brazil nuts from Wikipedia.

I don’t remember exactly how — I think it all started with rhymes we knew as kids that would not be acceptable in today’s society — but the topic of conversation turned to racial slurs. If you’re white and you’re old enough, you might remember certain phrases being quite common. It suddenly became a competition to list the common names for everyday things that would no longer be considered acceptable in polite society. (The one for Brazil nuts is a good example; Google it.) Then came company ad slogans and imagery. I admit that I hadn’t heard or seen many of them. I’m a bit younger than the others and maybe the fact that I had black friends and neighbors when I was a kid made it unwise for adults to mention such words and phrases in front of me. Growing up in the New York City Metro area probably had a bit to do with it, too.

(A side note here. I was born in 1961. Even in the late 60s and early 70s, my formative years, I had an idea of what a racial slur was. I clearly remember the day that one of my fourth grade classmates called one of my black friends a nigger in my presence. I nearly got into a fistfight with him and he didn’t do it again.)

Of course, a discussion like this is fuel for right wingers, who immediately start talking about how the country is “too politically correct now” and “people are afraid to say what they think.” And, of course, the husband of the Trump-supporting couple started going that way. He spoke up: “You can’t say those things now because it’s not politically correct.” He made sure to pronounce those last two words with as much scorn and ridicule as he could throw into their syllables.

I was already pretty much out of the conversation, not having anything to contribute and not wanting to contribute anything anyway. I honestly found the entire conversation disturbing and even rather shameful. But alarm bells were going off in my head. It was a nice afternoon and I was enjoying a glass of wine with people I mostly liked. (Yes, I even liked the Trump supporters when they didn’t talk about their political beliefs.) If the conversation went political, I’d have to make a quick exit and I really didn’t want to gulp the rest of my wine.

Fortunately, I wasn’t the only one hearing silent alarm bells. The group got quiet for a moment. Then someone else who had been in the conversation skillfully steered it in another direction. I breathed a sign of relief and joined the new conversation, eager to leave the old one behind.

Political Correctness Explained

I don’t remember when the phrase politically correct came into general use in this country. I’d Google it, but as I type this I’m sitting at a campground picnic table without any possibility of an Internet connection. I did use the dictionary built into my little MacBook Air to see what it would tell me. Surprisingly, it came up with a quote from Michael Dirda that says pretty much what I wanted to explain. I’ll let him say it for me:

The tediously overworked phrase politically correct can be used only with a smile, whether of irony or slightly embarrassed affection. Originally, the politically correct were those who ardently championed the rights of women, people of color, homosexuals, and other long-marginalized groups. But politically correct rapidly came to be associated with adherents who were overscrupulous in these observances, in short, zealots. Today most people recognize the fundamental justice of many, if not all, the legal and social advances linked to political correctness, but no one really cares to be called PC. The fight has largely been won, at least de jure if not always de facto, and so the term now sounds a bit old-fashioned, and usually carries an undertone of mild vexation or benign indulgence: Oh, Joan, she’s so politically correct!

I don’t know when Mr. Dirda wrote that, but in recent years, politically correct has taken another turn. It has been co-opted by the right to be slung as an insult to those on the left. These people don’t seem to recognize the justice of social advances linked to political correctness, as Mr. Dirda believes most people do. To them, political correctness is a farce — something to be laughed at.

And that’s a real shame.

Some Ideas are Incorrect

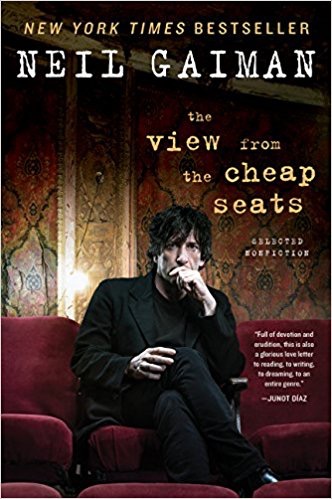

What got me thinking about this today, as I sit in a nearly deserted campground looking out at a secluded mountain lake in a smoky National Forest, is the very first essay in Neil Gaiman’s nonfiction compilation, The View from the Cheap Seats. That’s what I was reading just moments ago, while sitting in a folding chair facing out over the lake. Called “Credo,” it begins by talking about ideas. I don’t know where it goes from there — something on its very first page got me thinking about political correctness and I stopped reading while the idea to write this took control of me.

What triggered this overwhelming desire to write an essay about political correctness? This:

I believe that ideas do not have to be correct to exist.

How timely! This book was published in 2016, yet within the past month the war of ideas — both right and wrong — has been going strong. Charlottesville brought part of it front and center with a large gathering of Nazis, KKK members, and other white supremacists. This brought out protesters opposing their hate speech and resulted in violence when the two factions clashed, culminating in a senseless death and injuries of protesters when a white supremacist allegedly drove his car into them on purpose.

I think it’s an understatement to say that the ideas of Nazism and white supremacy are incorrect. Countless people around the world agree. These ideas are hateful and certainly un-American. America fought wars against these ideas and won. And, if need be, I’m sure we wouldn’t hesitate to fight them again.

The President of the United States should be, among other things, a moral leader who publicly, in no uncertain terms, condemns things that are widely accepted as un-American and downright wrong. Every president before him has done this after every American tragedy brought on by a difference in ideas — whether it’s Lincoln’s stand against slavery or Obama’s comments following the racially motivated shooting of elderly people at a church prayer meeting in Charleston.

Trump’s failure to condemn Nazis and white supremacists, in part, supports the view of his rabid followers that political correctness simply doesn’t matter. It also gives a boost to those who are pushing their morally wrong ideas, sending a message that their harmful, divisive views can be just as acceptable as those of the people who protest against them. It supports political incorrectness.

(And don’t try to tell me that morals should be left to religious leaders. Doing so reveals your own prejudices against those who don’t practice a religion — a growing percentage of the population throughout the world, including many of your neighbors, co-workers, and even friends and family members. Many of these people have higher moral standards than so many of the church leaders you look up to.)

The Importance of Political Correctness in Civil Society

Let me go back to our neighborhood gathering.

The racial slurs we talked about that weren’t necessarily recognized as such by white Americans in the 1950s and 1960s are still hurtful and wrong, especially today when we have a better grasp of how they affect the people they disparage. That’s what makes them politically incorrect. Is there anything wrong with that?

Are the people who mock those of us who try to be politically correct telling us that it’s okay be hurtful? That we can — or should — use language charged with racism or hate to inflict pain on our fellow men and women?

After all, isn’t that what political correctness is all about? Being sensitive to the feelings of other people?

And isn’t that a cornerstone of civilized society? Simply caring about our fellow man enough to have the courtesy not to insult or hurt him with words?

We don’t tolerate bullying in our school systems. Why should we tolerate it as adults in our everyday lives? Isn’t it the same? Using language or actions to spread hate and demean other people?

Isn’t being politically correct the same as being kind and civil?

What’s wrong with that?

Stop the Hate

There is an overabundance of hate and intolerance in today’s world. It has overwhelmed us, it permeates every fiber of our daily lives. It’s eating away at us from the inside, chewing away at our brains, making us blind to what’s good about other people and the world we live in. It’s stopping us from moving forward as a society; it’s preventing us from embracing our differences, learning from each other, and working together to make a better world.

We have the ability to stop it in its tracks. Being politically correct — not saying hurtful things to or about others — is a good way to start.

So yes, I’ll do my part. I’ll try to be politically correct — and be proud of it.

Discover more from An Eclectic Mind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

That Dirda quote has an especially interesting sentence in it: “politically correct rapidly came to be associated with adherents who were overscrupulous in these observances, in short, zealots.”

It embeds the idea that it’s OK to champion rights for various groups, but only up to a point. The idea that it’s possible to too much champion those rights — it should only be done so long as it doesn’t inconvenience those who would deny such rights.

The phrase politically correct also conveys the notion that one is embracing human rights only as a matter of convenience and appearance, for some political advantage and not because it’s the right thing to do.

For myself, I believe the only real way we can effectively combat that negativity is to at the very least embody the values we believe in that all humans beings are entitled to dignity and respect. Sometimes we may need to do more than merely embody those values and actually take action too, but as you say, it’s a start.

I recently discovered my guiding principle in life: to be an actively decent human being. For me, that helps me stay on track to do what I believe is the right thing in various situations.

Interesting post. Thanks.

Well said, especially that third paragraph. What I’ve realized lately, especially in regards to racism in this country, is that is very deeply ingrained in all of us. Some of us try to fight it and use the civility that comes with political correctness as a tool. Other just try to be PC to hide what they’re really thinking. And then there are the self-proclaimed Nazis and white supremacists who say nasty, hateful things regularly and seem happy about the pain they inflict.

I’m tired of being jeered at for trying to stay civil. There’s more than enough hate in this world. I don’t want to add to it.

The definition of the term “PC” seems to be continually evolving and comes with a LOT of baggage, especially when it’s being used as a pejorative. Frankly, the majority of what substitutes for civil discourse these days seems like a nationwide experiment in proving the prescience of the philosopher Karl Popper The following article makes for interesting reading, and seems particularly relevant in the Age of Trump.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paradox_of_tolerance

Thanks. I’ll give it a read.

Okay, I read it. And it IS very relevant in the age of Trump.

Are you saying that tolerant people should tolerate racist, homophobic, or hate speech? Or that this is where we draw the line and NOT tolerate it to avoid losing control to intolerant people? And how does this relate to the concept of political correctness as a form of civility?

These are complex problems which are difficult to discuss dispassionately. They form a cluster of related ideas and behaviours that seem to get tangled up.

In general, I favour free speech and the robust exchange of ideas, yet I agree that speech aimed at intimidating and demeaning is wrong.

History has revised our views of early political and military leaders but do I want to pull down statues to heroes who had racist views, when all in that era had racist views? No, I do not. Jefferson and Lee probably had very similar views on ‘race’. Both the ‘North’ and the ‘South’ recognised Lee’s genius as a leader, both wanted him on their ‘side’.

The greatest fighter pilot of all time, Erich Hartmann, wore a swastika on his uniform. I know nothing about his views about Jews but they were probably in conformity with those of the German military of that time. Hartmann probably had very similar social mores to Guy Gibson, another hero of mine. Had they met in the sky they would have tried to kill each other. Does that make me muddled or schizophrenic? I admire both for their outstanding courage and skill; character traits shared with Stonewall Jackson.

My best friend at school was a boy of mixed race (one of two non-White pupils in a roll of 600). We built model aircraft together and played music together, but when he ‘stole’ my first serious girlfriend we had a blazing row, a fight, and I called him ‘a nigger’. I had never used that word before, where had THAT come from? That nasty little word with so much power sprung up from what Freudians would call my ‘Id’, I suppose. I wanted to hurt him.

I am every bit as liberal and progressive as you, we share the same views on Trump. But there is a little bit of me that thinks that ‘political correctness’ merely suppresses unpleasant language rather than erasing toxic thinking.

I have never used the ‘N word’ out loud again, but clearly it still lurks within my ‘troubled’ psyche.

Let the statues stand. One day there might be a statue to Kate Millet, the feminist, who died this week. If, in two hundred years, a chauvinist culture is in the ascendant, should her statue be pulled down?

I’m thinking Ozymandias. (Percy Bysshe Shelley)

I think the statues, especially those of Civil War heros of the south that were erected in the 1900s as a sort of “fuck you” to the civil rights movement, need to go. I don’t think ones to honor fallen soldiers, especially those in cemeteries, need to be touched. It all has to do with the message the statue is intended to share. The Civil War remains a black mark on the history of this country. It was fueled by greed and racism, ideas that should never be glorified.

But yes, I agree that politically correct language merely suppresses the hurtful language and not the thinking. But, on the other side of the coin, suppressing the language helps erase the thinking in future generations. If we allow hateful, racist language to continue unchecked, we’re sending a message to young people that this language and the thoughts and ideas that go with it are okay. They’re not. They’re wrong.

I had trouble making my point in this piece — I went off on a slightly related tangent in my discussion of Trump and the Nazis — but I think my point is that eliminating hate speech from accepted civil discourse can only make things better, not worse.

Also note that nowhere in my discussion did I say that we should remove the freedom to make such speech. I just said it’s wrong and civilized people shouldn’t do it.

I love the Gaiman quote. The stories we tell ourselves are such a large part of who we become, and they don’t have to be true to be important. In fact there’s almost zero correlation between our conviction in something and whether or not it’s true. I think that’s a really staggering thought.

Take where we are when it comes to racism right now. I think there’s this perception that racism must contain hatred. I don’t HATE therefore I can’t be racist. But racism is really just the belief that another group is inferior. Is less than. Look back at the story of race in our country. Slavery was founded on the story of inferiority. White mans burden. Most people wouldn’t have been able to be a part of something so obviously wrong without a story that alleviated that guilt. That story is still so deeply bound up in who we are that we don’t even really see it anymore. There doesn’t have to be any truth to the story for it to change who we are and what we’re capable of doing to our fellow man.

I look at the rebranding of being politically correct as a bit of a character flaw in the same way I look at how brilliantly being liberal has been branded as a flaw or defect. I don’t necessarily see the opposite. I don’t see many liberals arguing that conservatism is a mental illness. Just a different point of view. It’s the crafting of a story, and it’s one that’s so toxic we’ve hit the point that we’re barely able to have a conversation with each other anymore. How can what I see as a desire to be conscious of each others feeling be a bad thing in any way?? How could you not want to always err on the side of caution? I seriously just don’t understand it. I can’t remember whose bit it was, but it reminds me of someone saying that there was something wrong when calling someone an Einstein had become a bit of an insult.