Why waste time flying around the airport or hogging up the runway when you just want to get on the ground?

Over the past nine or so years, I’ve done more than my fair share of long cross-country flights with newly minted commercial pilots or CFIs. In most cases, the purpose of the flight was to reposition my helicopter at a temporary base of operations 500 or more miles away and the typically 300-hour pilot on board with me was interested in building R44 time. I was on board as a passenger and got a chance to observe the things these pilots did — or didn’t do. I think the fact that I’ve never been a flight instructor gives me a unique perspective on what I observed.

One thing I’ve come to realize is that typical flight training does very little to prepare students for a commercial flying career. Instead, students are taught to perform maneuvers “by the book,” often so they can teach those maneuvers to their own students in the future. While it’s obviously important to know how to perform maneuvers properly, there are other concerns that are important to commercial pilots. In my upcoming posts for Hover Power, I’ll tackle a few of them, starting with traffic patterns.

I can tell lots of stories about new commercial pilots and CFIs entering traffic patterns to land for fuel at nontowered airports in the middle of nowhere. I can even tell you about the pilot who landed on the numbers of an empty airport’s runway, hover-taxied to the taxiway, and then hover-taxied a half mile down the taxiway to reach the midfield fuel island. They did this because that’s what they had been trained to do. That’s all they knew about landing at airports.

Our flight training teaches us a few things about airport operations, most of which are school-established routines at the handful of airports where we train. There’s a procedure for departing flight school helipads and there may be a procedure for traveling to a practice field nearby. Once there, it’s traffic patterns, over and over. Normal landing and takeoff, steep approach, maximum performance takeoff, run-on landing, quick stop, autorotation–all of these standard maneuvers are taught as part of a traffic pattern. It gets ingrained into our minds that any time we want to land at an airport, we need to enter a traffic pattern.

The reality is very different. Remember, FAR Part 91.129 (f)(2) states, “Avoid the flow of fixed-wing aircraft, if operating a helicopter.” Your flight school may have complied with this requirement by doing a modified traffic pattern at the airport, operating at a lower altitude than the typical airplane traffic pattern altitude of 1,000 feet, or landing on a taxiway rather than a runway. But despite any modifications, it’s still a traffic pattern.

But is a traffic pattern required for landing? No.

Experienced commercial pilots — and their savvier clients — know that traffic patterns waste time. And while the pilot might not be concerned about an extra few minutes to make a landing, the person paying for the flight will be. Why waste time flying around the airport before landing at it? Instead, fly directly to or near your destination and land there.

Before I go on, take a moment to consider why airplanes use traffic patterns. They enter on a 45-degree angle to the pattern to help them see other traffic already in the pattern. They then follow the same course as the other planes so there are no surprises. This is especially important at nontowered airports that don’t have controllers keeping an eye out for traffic conflicts.

But helicopters are avoiding this flow, normally by flying beneath the airplane TPA. As long as they stay away from areas where airplanes might be flying — remember, avoid the flow — they don’t need to worry much about airplane traffic. Instead, they need to look out for other helicopters and obstacles closer to the ground. If a runway crossing is required, special vigilance is needed to make sure an airplane (or helicopter) isn’t using the runway to take off or land. Obviously, communication is important, especially at a busy airport when a runway crossing is involved.

Now you might be thinking that this advice only applies to nontowered airports, where the pilot is free to do what he thinks is best for the flight. But this can also apply to towered airports.

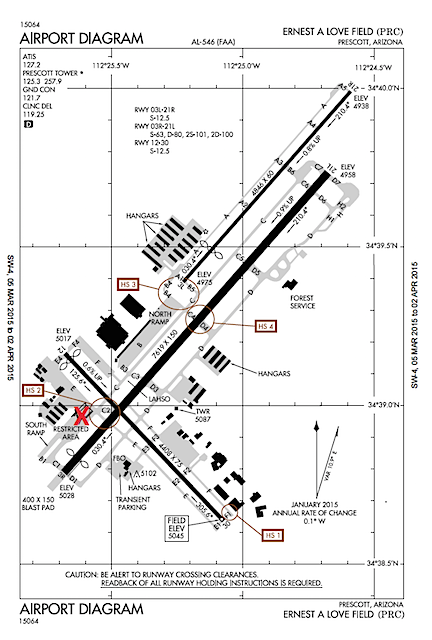

Airport controllers who are accustomed to helicopter traffic and understand helicopter capabilities may instruct you to fly to and land at your destination on the field. You must be prepared to do this, even at an airport you’ve never been to before. That’s part of what your preflight planning is all about. Consult airport diagrams or even satellite images of the airport. Know where you’ll be flying from and where you need to park. Imagine the route to that spot. Be sure to take note of where the tower is–it’s often a great landmark for navigating while close to the ground. Never assume the controller will put you in a traffic pattern. And don’t be afraid to admit you’re unfamiliar if you didn’t do your homework or if things in real life look different from how they looked on paper or a computer screen.

What if a controller does instruct you to enter a traffic pattern and you don’t want to? As amazing as this might seem to new pilots, you can ask the controller to allow you to go direct to your airport destination.

The airport diagram for Prescott. The X marks the location of the restaurant and we were coming in from the west. Runways 21L and 21R were active. The tower instructed us to fly all the way around the south end of the airport, at least three miles out, to get into a pattern for Runway 21.

I’ll never forget the flight I had one day as a passenger on my friend Jim’s Hughes 500c. Jim was a retired airline pilot who had been flying helicopters for at least 10 years. We were flying into Prescott Airport (PRC) in Arizona for lunch. When Jim called the tower, he asked for landing at the restaurant. The controller told Jim to enter a traffic pattern that would have required him to fly all the way around the airport, taking him at least 10 minutes out of his way. “Negative,” Jim barked into his microphone. “One-Two-Three-Alpha-Bravo is a helicopter. We want to land direct at the restaurant.” A new pilot at the time, I was shocked by his tone of voice. There was an uncomfortable silence and then the controller came back on and told him he could fly direct to restaurant parking.

Will the tower always grant your request? It depends on the situation. If a runway crossing is involved and the airport is busy with traffic, they might not. It might be safer or more convenient for them to keep you in a pattern with the airplanes. But it can’t hurt to ask, although I don’t think I’d be as aggressive as Jim was that day.

One of the big challenges of becoming a commercial helicopter pilot is thinking like a commercial helicopter pilot. There are things we can do that seem to conflict with what we were taught. Landing at airports without the formality of a traffic pattern is one of them.

Discover more from An Eclectic Mind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

well stated. yes, we need to train “standard maneuvers” but we need to teach aeronautical decision making…

Agreed! Teaching the standards is important to know how things are supposed to work and to fine-tune skills. I remember being taught traffic patterns mostly to make sure I did textbook takeoffs, climbed out at the right rate, reached the right elevation by the time I got to downwind, maintained that elevation, started descending before I got to base, and did a textbook landing. It was an exercise in controlling the helicopter more than anything else. Years later, when I learned to fly a gyro, we did the same thing for the same reason — although I guess gryos use traffic patterns, too.

The PIC, not ATC, has ultimate authority for safe operation. That said, the non-compliant pilot better have a good reason for refusing a command.

I envy your flexibility as a helicopter pilot. If you know the traffic pattern and you are talking to the tower, you will be safe to ‘go straight to the restaurant’, as you explain.

Us fixed wing pilots get far more grief. It is so irritating when approaching an airfield from six miles out, looking straight down an empty runway, bang into wind, with no one else on the frequency, to be told to do an “overhead join” and go all round the houses, when you could just fly straight in and save ten minutes.

Controllers who are also pilots (there are quite a few these days) are more helpful.

I once had to do a side slip to a landing to avoid a microlight which had strayed into the circuit. When challenged, I told the tower to look at the radar record. The controller had not noticed the microlight “because it should not have been there”.

But can’t you just request straight in?

I’ve also had bad instructions from a controller. In fact, I blogged about it: https://aneclecticmind.com/2004/10/09/on-close-calls/

I asked for ‘straight in’ when still four miles out. “Negative”, no reason given. No one landed or departed before me.

I looked at your link to your time with Papillon at GC. We were passengers of that outfit there! Up to the North Rim and back.

Most instructive, and you highlight the importance of carefully monitoring ATC clearances which are sometimes in conflict. That must have been a busy spot in tourist high season.

I have sometimes heard pilots ask ATC for urgent guidance only to hear that they are told to ‘standby’, followed by a long unhelpful silence. Hence the nickname ‘air tragic’, I suppose.

Heh. I never heard “air tragic” before.

I think flying in the U.S. might be a little easier. There are so many places we can fly without any ATC oversight at all. When I lived in the Phoenix area, at least I flew down around the city and had to talk to various airport towers once in a while. But up here, I rarely go near any towered airspace. My communications skills get rusty.

Flying at the Grand Canyon was an incredible experience that I recommend to anyone serious about making a career as a helicopter pilot. A LOT of challenges. I blogged about that, too: https://aneclecticmind.com/2004/08/21/thoughts-about-my-summer-job/

I read the link. Most interesting, thanks. Non pilots think flying is a glamorous doddle.

You demonstrate that it is damned hard graft in the early years.

Still, if I had to choose between 12 trips a day into the Canyon or 12 tedious hours in an A 380 to Dubai, I would go for the former.

I don’t regret my time at the canyon at all. I just wish I’d worked for a different operator. Papillon is not very nice to former employees they decide they don’t like. That particular blog post — which showed both pros and cons of working there — got me on a shit list.