Just because you can perform a maneuver, doesn’t mean you should.

In the summer of 2014, I was part of a helicopter rides gig at an airport event. There were three of us in Robinson R44 helicopters, working out of the same rather small landing zone, surrounded on three sides by parked planes and spectators. We timed our rides so that only one of us was on the ground at a time, sharing a 3-person ground crew consisting of a money person and two loaders. Yes, we did hot loading. (Techniques for doing that safely is fodder for an entirely different blog post.) The landing zone was secure so we didn’t need to worry about people wandering into our flight path or behind an idling helicopter.

The landing zone opened out into the airport taxiway, so there was a perfect departure path for textbook takeoffs: 5-10 feet off the ground to 45 knots, pitch to 60, and climb out. It was an almost ideal setup for rides and we did quite a few.

One of the pilots, however, was consulting a different page of the textbook: the one for maximum performance takeoffs. Rather than turning back to the taxiway and departing over it, he pulled pitch right over the landing zone, climbed straight up, and then took off toward the taxiway, over parked planes and some spectators. Each time he did it, he climbed straight up a little higher before moving out.

I was on my way in each time he departed and I witnessed him do this at least four times before I told him to stop. (I was the point of contact for the gig so I was in charge.) His immediate response on the radio was a simple “Okay.” But then he came back and asked why he couldn’t do a maximum performance takeoff.

It boggled my mind that he didn’t understand why what he was doing was not a good idea. The radio was busy and I kept it brief: “Because there’s no reason to.”

The Purpose

The Advanced Flight Maneuvers chapter of the FAA’s Helicopter Flying Handbook (FAA-H-8083-21A; download for free from the FAA) describes a maximum performance takeoff as follows:

A maximum performance takeoff is used to climb at a steep angle to clear barriers in the flightpath. It can be used when taking off from small areas surrounded by high obstacles. Allow for a vertical takeoff, although not preferred, if obstruction clearance could be in doubt. Before attempting a maximum performance takeoff, know thoroughly the capabilities and limitations of the equipment. Also consider the wind velocity, temperature, density altitude, gross weight, center of gravity (CG) location, and other factors affecting pilot technique and the performance of the helicopter.

This type of takeoff has a specific purpose: to clear barriers in the flight path. A pilot might use it when departing from a confined landing zone or if tailwind and load conditions make a departure away from obstacles unsafe.

The Risks

This is an “advanced” maneuver not only because it requires more skill than a normal takeoff but because it has additional risks. The Helicopter Flying Handbook goes on to say:

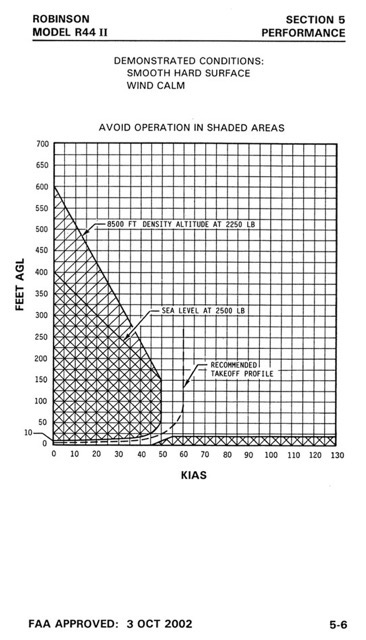

In light or no wind conditions, it might be necessary to operate in the crosshatched or shaded areas of the height/velocity diagram during the beginning of this maneuver. Therefore, be aware of the calculated risk when operating in these areas. An engine failure at a low altitude and airspeed could place the helicopter in a dangerous position, requiring a high degree of skill in making a safe autorotative landing.

Height Velocity diagram for a Robinson R44 Raven II. Flying straight up puts you right in the “Deadman’s Curve.”

And this is what my problem was. The pilot had purposely and unnecessarily decided to operate in the shaded area of the height velocity diagram with passengers on board over an airport ramp area filled with other aircraft and spectators.

Seeing what he was doing automatically put my brain into “what if” mode. If the engine failed when the helicopter was 50-75 feet off the ground with virtually no forward airspeed, that helicopter would come straight down, likely killing everyone on board. As moving parts came loose, they’d go flying through the air, striking aircraft and people. There were easily over 1,000 people, including many children, at the event. My imagination painted a very ugly picture of the aftermath.

What were the chances of such a thing happening? Admittedly very low. Engine failures in Robinson helicopters are rare.

But the risks inherent in this type of takeoff outweigh the risks associated with a normal takeoff that keeps the helicopter outside the shaded area of the height velocity diagram. Why take the risk?

Just Because You Can Do Something Doesn’t Mean You Should

This all comes back to one of the most important things we need to consider when flying: judgment.

I know why the pilot was doing the maximum performance takeoffs: he was putting on a show for the spectators. Everyone thinks helicopters are cool and everyone wants to see helicopters do something that airplanes can’t. Flying straight up is a good example. This pilot had decided to give the spectators a show.

While there’s nothing wrong with an experienced pilot showing off the capabilities of a helicopter, should that be done with passengers on board? In a crowded area? While performing a maneuver that puts the helicopter in a flight regime we’re taught to avoid?

A responsible pilot would say no.

A September 1999 article in AOPA’s Flight Training magazine by Robert N. Rossier discusses “Hazardous Attitudes.” In it, he describes the macho attitude. He says:

At the extreme end of the spectrum, people with a hazardous macho attitude will feel a need to continually prove that they are better pilots than others and will take foolish chances to demonstrate their superior ability.

Could this pilot’s desire to show off in front of spectators be a symptom of a macho attitude? Could it have affected his judgment? I think it is and it did.

Helicopters can perform a wide range of maneuvers that are simply impossible for other aircraft. As helicopter pilots, we’re often tempted to show off to others. But a responsible pilot knows how to ignore temptation and use good judgment when he flies. That’s the best way to stay safe.

Discover more from An Eclectic Mind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Well, what happened next? Did he comply , get mad, or learn and grow as a pilot?

Well, he complied at the event. He really didn’t have much of a choice. He was the third of three helicopters and the only reason he was flying was because we were so swamped with customers we needed to bring a third ship online. But I could have easily pulled the plug on him and he might have realized it. Or maybe — just maybe? — he realized I was right?

As for learning and growing as a pilot, I don’t know. I do know that I decided that summer that I wouldn’t use him again for cherry drying or rides. I really didn’t like his attitude — and I’m not the only one who remarked that it could be a problem.

What’s the old mantra we were all taught on day one of training?

“There are old pilots and bold pilots but no old bold pilots”.

Even if it is not strictly true, that old chestnut is an excellent training aid.

I speak with all the imagined authority of a PPL (A) but with less than twenty hours P1 on R22. ( A bit more on MT 03 gyros). I have spent far longer as a passenger in the front and back seats of Jet Rangers, Long Rangers and EC twins. So most of my helicopter time is as a passenger, not a trainee pilot.

I would not want to fly with the guy you describe. He might have skill but he is a chancer. You describe why with great clarity.

For me, the great buzz of helicopter flight is not a tenuous vertical ascent, but a gentle controlled lift into forward flight until translational lift, when clean air is drawn down efficiently through the rotor and then…wow! We are dipping slightly forwards and suddenly climbing really fast. That’s the adrenalin rush I cannot simulate in a C152 or 180.

Sustained vertical ascent, especially in a very crowded public space, such as the venue you discuss, is the triumph of ego over physics and airmanship.

But I sense this is one for Sean…

You describe the right kind of helicopter takeoff perfectly. That slow gathering of speed, close to the ground, with a slight dip that sometimes startles first-time passengers. Experienced pilots know when the dip will happen and know if/when they need to pull a tiny bit more pitch to stay airborne before reaching ETL and climbing out.

This post isn’t for anyone in particular — except perhaps for the pilots who still don’t get it. I don’t know any old bold pilots.

Love it. This is particularly relevant in this (new) age of Aeronautical Decision Making and Risk Management.

If you read NTSB reports, you’ve probably noticed the number of accidents attributed to poor pilot judgement. After all, at least 90% of accidents can be classified as “pilot error” — and that doesn’t even necessarily mean recklessness.

All I could think of was how many people would be killed or injured if he had an engine failure on one of those departures. Extremely unlikely, of course — Robinsons have an excellent record of engine reliability — but possible. Why risk it?