A blog post about pollinating corn with a helicopter.

The call came on Monday from someone who works with a very large agricultural manufacturer. Do I do corn pollination with my helicopter?

The only thing I knew about pollination by helicopter was the spreading of purchased pollen using a special piece of equipment installed in a helicopter. It was a two-person job — one to fly, one to measure out the pollen — and I didn’t have the equipment or experience. I’d actually looked into at the request of one of my cherry pilots this past winter, but when he didn’t seem interested in moving forward and I suspected I might need special certification for aerial application, I let it drop.

Besides, I didn’t realize helicopters were used for corn pollination. I thought helicopters just spread pollen over fruit orchards.

But this new potential client didn’t want me to apply pollen from the air. He wanted me to fly over the cornfields in such a way that the pollen would get blown about and do its fertilization thing.

The way he described it, it didn’t sound much different from the kind of flying I do when I dry cherries. Sure, I told him. I could do that.

The Field Guy

After sending the company a copy of my W-9 for billing purposes — big companies always want the paperwork first — I got a call from the field guy. We’ll call him Bill. Bill and I set up a meeting at the White Trail Produce farm stand in Quincy. It was a perfect place to meet, despite the fact it was an hour drive from my place in Malaga. White Trails makes the best peach shakes.

I was drinking a peach shake with Penny on her leash when Bill drove up. Although we’d never met, I easily guessed it was him — he had a plastic chemical tank on the back of his pickup. We sat down in the shade and talked about the work.

Wikipedia image “Corntassel 7095” by Spedona Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons; http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Corntassel_7095.jpg

The problem was this: as the corn was growing, a heat wave had set in. For the past nearly 2 weeks, the daytime highs had been getting into the high 90s and low 100s. The corn had formed tassels at the top — that’s the male part of the plant that produces pollen — and each day the packets of pollen were opening, ready for the pollen to be dispersed by the wind.

Wikipedia image “Cornsilk 7091” by Original uploader was Pollinator at en.wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia; transferred to Commons by User:Teratornis using CommonsHelper. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cornsilk_7091.jpg

Unfortunately, the extremely hot weather was killing the pollen within a few hours and the lack of wind was making it nearly impossible for the pollen to reach the corn silk — that’s the female part of the plant growing lower on the stalk — while it was still viable.

Bill’s corn fields needed wind — on demand.

That’s where I came in. They’d call me out to fly low over the corn fields at the time when the most pollen was being released by the tassels — likely between 8 AM and 10 AM. I’d fly back and forth, making sure all the plants got a good blowing. Once the pollen was flying around, gravity and mother nature would do the rest.

That was the plan, anyway.

Bill gave me four maps, each of which had at least a dozen or two corn field locations plotted on it. Each had a different number. They were scattered throughout an area that was probably 50 square miles. He said that each field was on its own schedule, so they would never all be done at once. Instead, only a handful would need to be done on a day.

That worked fine for me. I have a one-hour minimum for flights at my charter rate and would be spending at least 30 minutes round trip for travel time, which they would cover. If I could do two or three fields on a flight, it would likely come out to 90 minutes, which looked good for my bottom line and gave them more bang for their buck. Win-win.

I was booked with a photo flight in Seattle at dawn on Wednesday morning, so my first available day was Thursday. Bill said he’d call Wednesday night with a plan.

The Flight

Bill called Wednesday evening. I pulled out the maps. He listed two fields in Quincy and one in George. He asked me to be at the first Quincy field at 9:30 AM. He’d be on the ground, watching what I did. If I needed to make an adjustment in speed, altitude, or distance between passes, he’d call and let me know. Because the second field in Quincy was so close, he’d probably watch that one, too.

We hung up and I looked up the fields on Google Maps, knowing that the plantings in the satellite view might not match what was actually on the ground. I found the cross streets and noted the shape of the fields. I highlighted the fields on my maps.

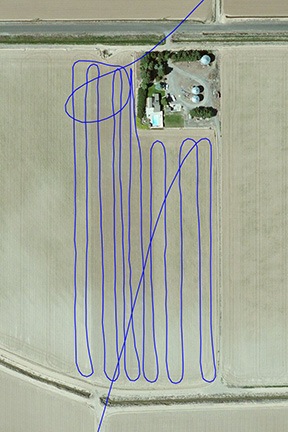

The first field was easy; all corn, no obstacles. I came in from the southeast and went back and forth to the north.

At 9:15 AM Thursday, I took off and headed to Quincy. After following Road 9 instead of Road 8 for about a mile past the field location, I doubled back and zeroed in on the first field. Bill’s truck was in the southwest corner. As I came in to make my first pass about 10 rows in, he got out of his truck to watch.

It took me a few minutes to get the hang of it; my brain wanted to dry cherries. But this was higher: about 15 feet rather than 5. It was also faster: 20-24 miles per hour rather than 5 to 10 miles per hour.

I looked back on my first few passes to see my coverage and realized that every 20 or so rows would be perfect — the corn was really blowing at least 20 feet on either side of the helicopter. (The corn rows were planted 22 inches apart.) I was probably on my third pass before I got the feel for where I should be and how fast I should be moving. I was on my fifth pass when I started making baby ag turns — not much more was needed at the speed I was operating.

Bill watched. I kept expecting my phone to ring, but it didn’t. When I got near the north end of the field, I realized I had an onlooker there, too.

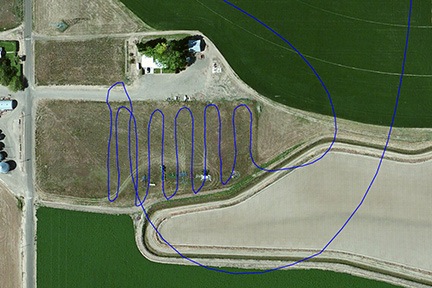

The second field had wires just outside the field. I came in from the north over the wires, circled around, and went up and down the rows. This satellite image doesn’t show the field as it appeared during the flight, of course.

I got through the first field, which was the largest, in about 15 minutes. The second field was right across the road. The were wires on both ends of it, but they weren’t that close to the corn. I made my turns inside the field so there was no need to go anywhere near the wires. Bill repositioned to the north end of that field to watch. When I was nearly done, I realized he was on the phone. Again, I expected my phone to ring, but it remained quiet.

This is the last field, which was fully planted with corn. This image doesn’t show the irrigation pivot, but if you look closely enough, you should be able to see the wires on the west side.

I finished up and headed to George. I found the field a lot easier than I expected to, but didn’t like what I saw. Not only did it have an operating irrigation pivot in it, which would force me to fly higher, over the pivot arm when I reached it, but there were what we call “Bonneville” power lines — the tall towers with multiple high-tension power lines between them. The power lines definitely crossed the field. To cover the corn, I’d have to fly under the wires very close to the tops of the plants. Suspecting that I might do more harm than good to the plants — and possibly to the helicopter — if I attempted to fly under the wires, I did only 2/3 of the field before heading out.

There was a house on the north side of the field and about five people had watched me work. I was only there about 5 minutes.

I called Bill and told him I’d finished, what part of the George field I’d missed, and why I hadn’t done it all. He seemed to understand. He also seemed very pleased. I wondered whether he could see the pollen dust on the plant silk. I hoped he’d have some kind of quick confirmation that our “wind on demand” scheme had worked.

I flew back and parked at home. I’d logged just 1.1 hours of flight time.

Repeat Performance?

Want to learn more about how corn pollination works? Read this.

And the title of this post isn’t something I dreamed up. It’s from this song, which was covered by Robert Goulet and others. And maybe — just maybe — it inspired Jim Hendrix to write this song.

Will I do this again? I hope so. It was kind of fun and a welcome break from cherry drying and passenger work.

But it all depends on the age of the corn and the weather. To need me, three things must happen at once:

- The corn must be ready to pollinate.

- It must be more than 85°F.

- There can’t be much wind.

If all three of this conditions apply, my phone might ring with a request to fly in the morning.

I’ll be waiting for it. I need to practice my ag turns.

Discover more from An Eclectic Mind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Very cool, Maria!! I hope you get more of this work, too. Love it!!

Thanks, Shirley!

It’s relatively easy flying, although I bet I can get more efficient if I get those ag turns perfected. Not anywhere near as tedious as drying cherries, but then again, I make more money drying cherries. If I could do this twice a week in the summer months, I’d be a very happy camper.

Maria,

I am working on a project for my Commercial Ground Class and your blog has been very helpful. I appreciate the details, which was so helpful, and your writing experience also makes this a very fun read. Thanks again and maybe in this small aviation world we will get to meet.

Dave