I lucked out. It was very easy.

The call came while I was hovering over 35 acres of cherry trees in Monitor, WA. It was my friend Katie, who lives in Quincy. The bees that live in the wall inside the shop at their home had swarmed again. They were gathered in a bunch on the maple tree, about 8 feet off the ground. Did I want to catch them?

Of course I did!

My only problem was that I was working — with no end in sight. I spend my summers as a cherry drying pilot and I was into what would become a hellish week of rain and lots of hard work. I was hovering over one orchard when she called and another was already waiting for my attention. I told her I’d get there as soon as I could, thanked her for her patience, and hung up.

About Bee Swarms

Before I go into the story of this capture, let me take a moment to educate readers about bee swarms.

Honey bees live in hives. They could be manmade hives like the one I (and countless other beekeepers) have. Or they could be hives built inside of structures not intended to house bees, like hollow trees, rock overhangs, or building walls.

Most hives have a finite amount of space in which to build. Bees exist to reproduce and increase their numbers. Everything they do is to meet that end. (The honey they make is really for their consumption, not ours. They just make a heck of a lot more than they need.) So they’re constantly building inside their hive, making wax cells for brood (eggs laid by the queen and the larvae they turn into) and the storage of food like nectar (which turns to honey) and pollen.

As the hive population grows, the bees eventually start running out of space. They realize this and instinctively plan to split the colony. First, they create queen cells, which are special large brood cells for raising queens. The existing queen lays an egg in each of these cells, as she does for all the other brood cells. The workers, however, raise the larvae in these cells to be queens by feeding them royal jelly. (All larvae are started on a diet of royal jelly, but only future queens get it throughout their development.) Workers raise queens when they sense that the current queen is ready to die or already dead or when they know they need to swarm. The positioning of the queen cells helps beekeepers determine what’s going on; swarm cells normally appear at the bottom of the hive while supersedure cells appear near the top.

The swarm I caught looked a lot like this one. Wikipedia image by Mark Osgatharp.

Before the new queens emerge from their cells, the existing queen leaves the hive with at least half of the bees. They’ve already stuffed themselves with food so they’ve got enough energy to make a journey. This is the swarm. The bees stay close together, surrounding the queen to protect her. They leave the hive and often fly to a nearby location where they alight as tight mass on a branch or building eave or some other surface. They’ll remain there to rest and organize and get their bearings. Scout bees might fly off in different directions, looking for a new home. Eventually, the swarm will take off and fly in a bunch to a possible future homesite or another rest stop.

In general, when honey bees are swarming, they are least likely to sting. Why? Well, they don’t have a hive and food stores to protect. They’re on the go. Their only concern is protecting the queen and moving her into a new home so she can continue laying eggs and building their population.

Capturing a swarm is a win-win-win-win situation:

- The property owner wins because she gets the bees removed for free.

- Society wins because the bees are kept alive rather than killed — as an exterminator might do. Bees are vital to agriculture and the food chain.

- The bees win because they’re not only kept alive, but they’re given a great new home all ready for them to move in — a manufactured hive, designed with their needs in mind.

- The beekeeper wins because she gets a whole colony of bees, including a queen, for free.

Wikipedia, by the way, has an excellent article about honey bee swarming.

My Swarm Capture

I finally finished flying for the day at around 6 PM. I wasted no time loading up my beekeeping gear, which I keep in a rolling storage box, and the empty nuc box I’d gotten my first been colony in. My friend Cheryl climbed aboard the truck with me and we drove the 10 or so miles to Katie’s house.

Katie, by this time, was gone. She had to take her son to a swimming meet (or ball game or something like that). Her other son was home. He came out when we pulled up with the truck. The swarm hung from a branch on a maple tree beside their driveway. It was about 10 feet off the ground. But because it was overhanging the driveway, I could back my pickup’s bed under it. Standing on the pickup bed didn’t get me close enough to reach it, but standing on that big plastic bee equipment box in the back of the pickup did. (I really don’t like climbing ladders.)

I suited up and took a closer look, climbing up until my face was less than a foot from the swarm. They clung to a pair of small branches. I knew from conversations with other beekeepers that capturing a swarm like this was often as simple as clipping the branch off the tree and putting the bees in the box. So that’s what I did.

Cheryl took this photo of me lowering the bulk of the swarm into the nuc box.

I removed three frames from the 5-frame nuc box. Katie’s son got me a pair of clippers (note to self: buy clippers and put in bee box) and I climbed back up atop my equipment box. I grasped the branches right above the top of the swarm and clipped them right above my fingers. I then lowered the branch into the box. That took care of about 80% of the bees. I repeated this process for another small branch. Unfortunately, a clump of bees fell off and landed in the bed of my pickup. I had to scoop them up manually with some cardboard to get them in the box. When I was done, I had about 98% of the bees. A few dozen were flying around.

The captured bees wasted no time crawling up onto the frames in the nuc box I put them in.

I looked into the box. There was plenty of space in there to add a frame, so I gently lowered one in.

By that time, Katie’s husband had come out. He, his son, Cheryl, and I took a close look inside the box. We could clearly see “fanning” activity by a handful of bees on the top edge of the box. I’d seen this behavior before when watching another area beekeeper catch a swarm. The bees were trying to spread the queen’s scent outside the box to attract other colony members who hadn’t come into the box yet. That’s a great indication that the all-important queen was inside the box.

I took off my suit and stowed it in my equipment box, along with my smoker (which I hadn’t needed) and gloves. I waited as long as I could to cover the nuc box.Most of the bees were inside the box; the ones left behind might find their way back to the original hive in the shop wall less than 100 feet away. The plug for the hive entrance had already been put in place so the bees inside the box were trapped there. I wedged the box into a safe spot in the back of the truck, said goodbye to Katie’s family, and left.

Settling in the Swarm

Back at my RV, I offloaded the truck, leaving the nuc box on top of the bee equipment box under my fifth wheel hitch overhang. Then I took a quick shower, dressed, and went out with Cheryl to meet some friends in town.

The plan was to take the bees with me the next day when I moved my RV to Wenatchee Heights. Unfortunately, the weather didn’t cooperate. I had to fly most of the morning. If I left the bees closed up in the box, they could die from heat or lack of water. So I took the door plug off. Bees started coming and going like a regular hive. This meant that I would not be able to move the bees until that evening, when they returned for the night.

Although I did manage to move my RV that evening, I also had to fly. By the time I was done, it was too late to retrieve the bees. I asked Mike and Cheryl to close up the door, planning to retrieve them in the morning. But when morning came, I had to fly again. So they opened the door to let the bees out another day.

This turned out to be a tiny problem. Although I’d paid for my RV space through the next day, the campground people put a motorhome in that spot. The bees were coming and going from their box under the picnic table. The motorhome people were terrified of them and stayed locked up in their luxury box. The campground people called to ask when I’d get the bees. I was flying when they called. I assured them I’d be there later that evening and hoped (again) that the rain would stop.

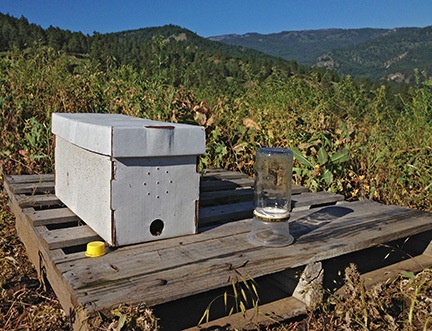

My new bees in their temporary home. I hope to have them moved into a real hive later this week.

Fortunately, the rain did stop and I did get back to Quincy to retrieve my bees and other possessions left behind. I brought everything back to Wenatchee Heights, where I’m currently camped out between two of the orchards I’m contracted to dry. In the morning, I opened the door to the hive. The bees began coming and going as usual, probably wondering what the heck was going on.

Several days have gone by. The bees seem happy enough. I’ve ordered a new hive to put them in; it should arrive sometime this week. I’ll set that up here, remove the frames from the nuc box and put them in the new hive, and get the nuc box ready for my next swarm capture. Details to come (of course).

Discover more from An Eclectic Mind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Awesome read Maria!

Thanks!

Shades of Lee. I had to giggle, he couldn’t pass up free bees either, and that’s how we ended up with 33 hives!

I passed up two opportunities to capture swarms this past week simply because my only nuc box already had bees in it. So I ordered two more nuc boxes to capture swarms. I’d very much like to sell nucs as a way of bringing in revenue for future hive development. If I do catch another swarm, I’ll try raising it in a nuc box and offering it for sale. If it doesn’t sell, I’ll put it in a hive before it gets too crowded. Around here, a nuc can sell for $100. That’s not bad, especially if I can catch a few swarms every summer.