Notes from another flight.

I’m still in Las Vegas, attending an HAI-sponsored helicopter tour operator summit. And since I had such an enjoyable flight up here from Wickenburg, I thought I’d share some of the highlights with folks interested in that kind of stuff.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any photos. My little Canon PowerShot seems to go into convulsions ever time I turn it on and I can’t take a picture with it. I didn’t feel like dealing with the Nikon SLR while flying — you think it’s easy to use a camera while flying a helicopter? — so I just didn’t get any shots at all. If I fly home the same way, I might try the Nikon.

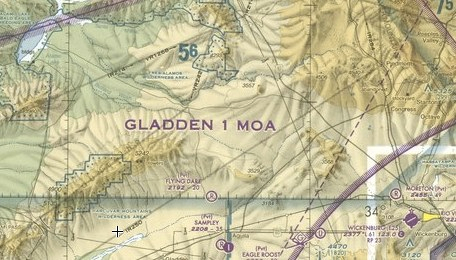

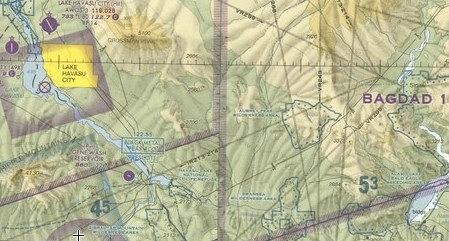

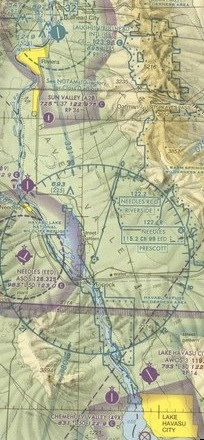

I did include images from sectional charts, however. If you’re a pilot, you’ll recognize them. If you’re not a pilot, see if you can follow my path on the chart segments; unfortunately, this computer doesn’t have any good annotation tools on it, so I couldn’t mark up the images before uploading them.

Wickenburg to Lake Havasu

I got off to a late start from Wickenburg — I almost always do — departing from the west end of the ramp to the west. There was an airplane on final as I departed, but he was still a way out and I had plenty of time to get on my way. I was surprised, however, when he called a go-around when I was still in the traffic pattern area. I used my radio to assure him that I’d stay low until I was clear, giving him all the room he needed to climb out and do another traffic patter.

A go-around, in case you’re wondering, is when the pilot decides that he’s not going to actually land as he approaches the runway and, instead, powers up and climbs out for another try. Pilots do go-arounds when they’ve botched up the approach or if there’s something in their way on the runway. (I experienced my first airliner go-around on Saturday evening when there was a plane on Sky Harbor’s runway and the tower instructed our flight to go around.)

I continued on my way, flying low across the desert. Just past the hills near Wickenburg Airport, the desert gets flat. Since there aren’t any homes out there, its an excellent place to practice low flying. So I did. I scooted along about 100 feet up, doing about 110 knots. Below me was dry desert terrain with scattered bushes and cacti and the occasional rock outcropping.

I was at least five miles away from the airport when the airplane pilot who’d gone around and made all his subsequent radio calls in the pattern announced that he was going around again. That made me wonder: (1) What’s keeping this guy from landing? (2) Does he know how to fly a plane? (3) Will he ever land at Wickenburg? I switched the radio’s frequency to 122.7 for Lake Havasu, my first waypoint.

I climbed to about 300 feet to clear the high tension power lines that run southwest to northeast across the desert. Then I skirted the edge of a rock outcropping that’s obviously made of ancient volcanic material. Arizona has a lot of volcanic rock, although this area lacks the cinder cones you can find in quantity in the vicinity of the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff. Instead, all we have is that dark brown rock, all sharp and crumbly. It forms hills and small mountains and sometimes volcanic core mountains like Vulture Peak, south of Wickenburg.

From there, the desert slopes mostly flat down to a basin where three water sources meet. A dam at the west end of the basin holds in Alamo Lake, Arizona’s attempt to keep some of its precious water from entering the Colorado River, where it would become fair game for California. I changed to a more northwestern course, hoping to hook up with the dirt road that runs from Route 93 to Alamo Lake. Once I reached the road, which was completely deserted, I followed that, low-level, toward the lake.

The road was narrow, sandy, and a bit windy where I picked it up. But it soon led me to the more maintained part, which is wider and straight. I flew for about 10 miles without seeing anyone. Then I caught sight of a pickup truck up ahead and decided to climb a bit so he didn’t think I was going to hit him. (For the record, I was low, but not low enough to hit a truck.) The Wayside Inn was up ahead and I didn’t want to blast past the folks living in trailers there.

The Wayside Inn property looked different to me and it took a moment to figure out why. The Inn was gone, with only a concrete slab to show that it had ever been there. I wondered what happened to the place. Had it burned down? There was no sign of fire. I wondered what happened to the Polaroid photos of people’s trophy fish and the pool table and the bar. I wondered if it would ever be rebuilt. And I realized that I could no longer promote my “Hamburger in the Middle of Nowhere” tour. Another destination, gone.

I reached the lake, which was surprisingly full. We’d had some rain about a month ago and the dam operators had apparently decided to keep as much water as they could. There were quite a few trailers and motorhomes parked near the eastern shore, but not many boats out on the lake. Alamo Lake is a fishing destination. It’s too small and remote for much else.

I crossed the lake and started to climb again. There were mountains to cross and I needed to climb from my current altitude of 2,000 feet to about 5,000 feet to clear them. The desert on this side of the lake was full of rocky outcroppings with a few winding roads leading to old mines and a few newer roads leading down to the lake’s west shore. I didn’t see a soul as I continued on my way, using Grossman Peak in the distance as my navigation tool.

I leveled off when I reached an altitude that enabled me to cross all the rock outcroppings and mesas in front of me without changing altitude. I was actually flying a lot lower — maybe 500 feet lower — than I usually did in that area. I don’t particularly care for this part of the flight. There’s too much of that volcanic rock, few roads (although there is a buried pipeline), and not much of interest to look at. But I was rewarded for my low altitude. I caught sight of a natural arch in one of the volcanic outcroppings — something I’d never seen there before.

I crossed a detached mesa and the canyon beyond it. Then I was over a relatively smooth sloping hill, at the south end of Grossman Peak, descending toward the lake. I could see the lake in the distance, as well as the manmade island that was home to the old airport. (The current airport is about 10 miles north of town and is extremely inconvenient for anyone flying in.) A few minutes later, I was flying down the canal the founders of Lake Havasu City had dug so they’d have a place to put London Bridge.

If you’ve never head this story, it’s worth taking a minute to read about it. The guys who first imagined Lake Havasu City decided that they needed a tourist attraction. At around the same time, the City of London was getting ready to take down London Bridge and replace it with a new bridge. The Havasu guys bought the bridge and had it shipped over to the U.S. They trucked it out into the middle of the desert alongside this lake and reassembled it on the canal. It’s a very attractive bridge, but nothing terribly special. When Americans think of “London Bridge,” they usually think of Tower Bridge. That’s not what the Brits sold us. They sold us London Bridge, a simple stone arch structure. So when people see it, they’re usually pretty disappointed.

Anyway, Lake Havasu is formed by the Parker Dam on the Colorado River. It’s not part of the national recreation area system, so it’s not subject to Federal rules and regulations that “protect” Lake Mohave, Lake Mead, and Lake Powell farther upstream. A lot of people live at Lake Havasu City, but I doubt most of them are there year-round. Temperatures get into the 100s six months out of the year. It’s like hell, with a lake.

There were pilots doing touch and goes at the airport. Most of them spoke with German accents. Lufthansa pilots in training from Goodyear. I expected them to do instrument approaches to Needles airport next.

Lake Havasu to Bullhead City

I followed the eastern Arizona shoreline of Lake Havasu uplake. I wasn’t flying very high, so I needed to stay within gliding distance of land, in case I had an engine failure. Pilots are programmed to think like that.

I followed the eastern Arizona shoreline of Lake Havasu uplake. I wasn’t flying very high, so I needed to stay within gliding distance of land, in case I had an engine failure. Pilots are programmed to think like that.

Although the lake was nearly full — it usually is — the water was clean and clear enough for me to see the bottom of the lake in many places. I assume it was much shallower there. I could also see the patterns the water makes in the sand as it flows over it. Although this is a lake, there’s a definite flow of water from north to south.

There weren’t many people on the wide part of the lake and even fewer uplake in the Topok Gorge area. This is a beautiful part of the lake, where sharp rock cliffs narrow it down to a river-like area — a glimpse of what it might have been like before the dam and lake existed. It’s a wilderness area and aircraft are requested to stay 2,000 feet or above. I admit I wasn’t that high. It always bothered me that I had to stay so far from the lake in this spot while thunderously loud race boats could scream though it all day long. But the people who take care of the lake may have put a stop to that. I saw buoys across the water in two place in the gorge. I’m not sure if they were setting up a speed zone or if they’d closed that section off completely for some reason. There weren’t any boats in it. It would be a shame if it were completely closed. Mike and I had once taken a pair of wave runners from Lake Havasu to Laughlin, NV on this route; it was a fun trip that others with appropriate equipment — ie., watercraft suited for operation in shallow water — should be able to enjoy.

After the Gorge, the landscape opened back up and the river widened again. I dropped down to follow it a few hundred feet up, banking left and right to stay right over the center of the channel. There were people camped out alongside the lake in trailers and motor homes in what must be a primitive camping area. It was just north of where I-40 crosses the river; I hope to be able to check it out one day soon with our camper. There were a few small boats on the water and their occupants waved up at me as I flew over. I also passed the Laughlin to Havasu jet boat, a tour boat that runs once a day from Laughlin to the London Bridge. All along this stretch of the river, the water was very shallow and I could see the bottom from the air. In a few places, there were even small rapids (ripples).

I followed the river faithfully, climbing every once in a while to make sure I was clear of wires crossing from one bank to the other. I was tuned into the Bullhead City airport frequency. There’s a tower there but very little traffic. One plane had a short exchange with the female controller there. Ten miles out, I figured it would be a good time to check in.

“Bullhead Tower, helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima is ten to the south over the river. Requesting transition up the river at about 1,000 feet.”

The reply came quickly. It isn’t as if she had much else to do. “Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima. Transition approved at or above 1,000 feet. Current Bullhead altimeter is Three-Zero-One-Two. Report two miles south.”

“Zero-Mike-Lima will report two south,” I replied as I made a miniscule adjustment to my altimeter.

I was at 800 feet, but I was still a few miles short of their airspace. And I was enjoying my zig-zagging flight up the river. So I kept at my current altitude and kept enjoying the flight.

Meanwhile, below me on both sides of the river, were homes built right up to the river’s banks. The water was very low here and a few boats that had been tied up to docks were sitting high and dry on sand. The river’s water level is determined by the Davis Dam, just north of Bullhead City and Laughlin. When power is needed, water is released to generate power. This usually happens during the day. So the water is at its lowest level just south of the dam around dawn. Little by little, the water level rises. But the water doesn’t reach everywhere at the same time. So 20 or 30 miles downstream, the water level might not rise until 10 AM or thereabouts (depending on the season, the electrical needs, etc.) . The same thing happens in the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, but on a much larger scale, with water released from the Glen Canyon Dam at Page.

I approached the green dotted circle on my GPS that signified Bullhead City’s airspace and climbed obediently to 1,000 feet. I crossed the green line and continued on my route. The 200 foot climb really seemed to distance me from the terrain.

I passed the remains of a high-rise hotel/resort/casino that had begun construction years ago. It was a rotting frame of concrete and steel on the Nevada side of the river, surrounded by a chain-link fence to keep out the vandals. Abandoned long ago, I wondered whether anyone would ever finish or demolish it.

I should probably explain why there’s a towered airport with hardly any traffic alongside the Colorado River in the middle of the desert. Bullhead City is the Arizona side of the Laughlin/Bullhead City area. Laughlin, on the Nevada side, is a sort of baby Las Vegas. It’s a gambling town with a few high-rise hotel/casinos and all the crap that goes with them. It’s popular with the seniors from the Phoenix area because its a lot cheaper than Vegas — hell, you can get a decent room for about $25 midweek and all-you-can-eat buffets start at about $6. Busloads of seniors leave Sun City, etc. daily, taking these folks up to the slots in Laughlin.

It’s a depressing little town, mostly because when it’s full, its full of sad old people who are hoping to turn that social security check into the next big progressive slot jackpot. Mike and I once witnessed two oddly dressed seniors stuffing food into their pockets at one of the buffets. (I’m not talking about stealing a roll or a pastry or some fruit; these people were taking unwrapped pork chops and pieces of ham and turkey. It was really gross to watch.) And once a year, the Harley boys descend on the place with their loud motorcycles and tattoos and guns. A few of them got shot right on a casino floor one year. It’s an ugly scene.

Bullhead City, across the river where there is no gambling, is the support town. Laughlin workers live there. There’s a great little airport with free transportation across the river provided by the casinos. There’s also the usual collection of in-the-middle-of-nowhere businesses that you need to survive: supermarkets, hardware stores, etc.

“Bullhead Tower, helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima is two miles south.”

“Zero-Mike-Lima roger that. Report clear to the north.”

“Zero-Mike-Lima.”

Since the casinos were right on the river and I was flying right up the river, I flew about 100-200 feet past their rooftops. Down below, on the riverfront walkways, few people wandered about. Lots of cars in the parking lots, though. I guess the slots were getting a post-Thanksgiving workout.

Bullhead City to the Hoover Dam

I continued up river, now climbing to clear the wires just south of Davis dam and the dam itself. Beyond the dam was Lake Mohave. There’s a marina on the eastern shore, not far from the dam. Otherwise, the lake is completely undeveloped, part of the Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

I continued up river, now climbing to clear the wires just south of Davis dam and the dam itself. Beyond the dam was Lake Mohave. There’s a marina on the eastern shore, not far from the dam. Otherwise, the lake is completely undeveloped, part of the Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

Lake Mohave has an interesting shape. The southern end is pretty narrow, as the river passes through some mountainous terrain. But ten or so miles beyond that, the mountains fall back and the lake sits in a huge basin. It gets very wide here. Farther up is Black Canyon, where it becomes a narrow stream in a twisting canyon.

I don’t recall seeing a single boat in the wide part of the lake. Maybe because it was windy — I was flying in a 20-knot headwind. I flew along the Arizona shore, dropping low again to check out the terrain. There were small trees growing right up alongside the lake and the skeletons of dead trees stuck out of the water. At one point, I caught sight of a herd of wild burros. There had to be about a dozen of them, including some babies. I zipped past without bothering them much, and kept looking for more. That’s when I caught sight of two park ranger trucks on the shore. They gave me a good look, but I must not have bothered them much because I haven’t gotten a phone call.

I should mention here that there’s no minimum altitude for helicopters operating under FAR Part 91. So theoretically, I could have been skimming 10 feet off the ground and I wouldn’t have been breaking any rule. But that’s really not a good and safe thing to do, even in the middle of nowhere. So I was about 200 feet up. Since I wasn’t in a wilderness area, there really wasn’t anything the rangers could complain about. Maybe they knew that. Or maybe, more likely, they didn’t think it was such a big deal since I wasn’t being a nuisance. Just a pilot passing through.

As the lake began to narrow, I realized that I hadn’t called Bullhead to tell them I was clear. I was now about 20-30 miles north and wasn’t sure if my radio would reach them. I climbed to increase my chances of success.

“Bullhead tower, helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima?”

“Zero-Mike-Lima, Bullhead Tower.” Her voice came through scratchy. I continued to climb.

“I forgot to call clear. Sorry about that. I’m definitely clear to the north.”

“No problem. Thanks for calling.”

After considerable squinting at my Las Vegas terminal area chart, I switched to the frequency in use by helicopter tour operators in the vicinity of Hoover Dam. I was about 10 miles short of the dam, entering the bottom of Black Canyon. The dark canyon walls climbed up on either side of me and I climbed with them. This was harsh terrain where an engine failure would be a very bad thing indeed. But it was also beautiful, in a dark and mysterious kind of way. The river wound between the rock walls with a few power boats on its surface.

After considerable squinting at my Las Vegas terminal area chart, I switched to the frequency in use by helicopter tour operators in the vicinity of Hoover Dam. I was about 10 miles short of the dam, entering the bottom of Black Canyon. The dark canyon walls climbed up on either side of me and I climbed with them. This was harsh terrain where an engine failure would be a very bad thing indeed. But it was also beautiful, in a dark and mysterious kind of way. The river wound between the rock walls with a few power boats on its surface.

I knew I had the right frequency when I started hearing the tour pilots giving position reports. Most of them were considerably higher than I was — for reasons I would discover at the tour operator summit I’d flown to Las Vegas to attend. This meant the chance of meeting one of them midair was very slim. But to be safe, i started calling out my position when I passed Willow Beach.

Willow Beach, by the way, is home of a fish hatchery about five river miles south of the dam. There’s a campground and day use area down there, too, right on the river. I’ve been there a few times. You can get there by car by making a turn off route 93 a few miles before (on your way north) or after (on your way south) of the dam. Seeing it from the air really made it clear how small the place is.

A Papillon helicopter pilot made a call that he was crossing the river at 3000 feet. I looked up and saw him 1000 feet above me, to my left. If they were going to fly that high, I had room to climb, so I did.

Then the construction cranes for the bridge came into view. The bridge has been under construction for a few years now. When finished, it’ll be a high river crossing, just south of the dam. Right now, all traffic crossing in the area has to drive over the dam. This is how it has been since the 1930s, when the dam was built. In fact, the dam is the only crossing in the area. The next crossing upriver is at Marble Canyon, which is on the other end of the Grand Canyon. The next crossing downriver is at Bullhead City/Laughlin, south of Lake Mohave.

Because of terrorist concerns, trucks are no longer allowed to cross over the dam and all cars are stopped for a search before crossing. And, to further mess up traffic, the dam has only one lane in each direction, forming a pretty good bottleneck for traffic.

But I remember the days when you could not only drive anything across the dam, but you could park on it. That’s right: there were parking spaces on the sides of the road along the top of the dam. You could park, get out, and walk around up there. If you wanted a tour of the dam’s innards, it would cost you a whole dollar and would be led by a volunteer. The dam became such a popular tourist attraction that they decided to cash in on it. They built a new visitors’ center and multi-story parking garage. Now they charge a few dollars to park your car and $8 per person to tour the dam. And with terrorist concerns, I don’t think the current dam tour is quite as complete as the old one.

Such is progress.

I would have enjoyed my overhead view of the bridge under construction and dam if it weren’t for the tour helicopter making some sort of S-turn right over it. The pilot was a bit higher than me, but since I didn’t know his route, I had to keep an eye on him. We exchanged a few position reports and he explained which way he was going. I told him I was at his 9 o’clock and he finally caught sight of me. I passed behind him. By then, I was pretty much past the dam. And since I was concerned about other traffic in the area, I didn’t circle around for another look. Maybe I’ll get a better view on the return flight.

Hoover Dam to Las Vegas

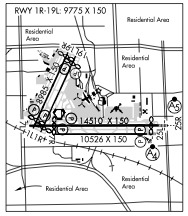

I’d decided to fly into McCarran Airport, which is the main International airport at Las Vegas. It was mostly an economic decision. Usually, I fly into Henderson, which is south of there. It costs me $7/night to park there and about $40 each way for the cab right to the Las Vegas Strip. It’s a much more laid back airport, with just two runways and friendly folks in the tower. Relatively stress-free. McCarran, however, is at the south end of the Strip, so ground transportation would be much cheaper. Sure, I’d pay $20/night to park and I’d be required to buy at least 25 gallons of fuel at a whopping $6.53/gallon to avoid a $50 ramp fee, but I’d save on the cab fare. I’d also save time by flying an extra 10 minutes and avoiding the 30 to 45-minute cab ride. As it turned out, I even saved on the cab far, since the FBO gave me a free lift to my hotel and I just tipped the driver $5.

McCarran is huge: two pairs of parallel runways that meet at the southwest corner of the field, numerous FBOs, a least a dozen tour helicopters coming and going, and jets of all sizes landing and taking off and just taxiing around. I admit I was nervous about coming into such a big place. But one of the things about being a commercial pilot is that you have to be prepared to fly into any airport that a client wants to fly into. Coming into McCarran would be good practice in case I ever needed to do it with a client on board. That, in fact, was another reason I’d decided to land there.

McCarran is huge: two pairs of parallel runways that meet at the southwest corner of the field, numerous FBOs, a least a dozen tour helicopters coming and going, and jets of all sizes landing and taking off and just taxiing around. I admit I was nervous about coming into such a big place. But one of the things about being a commercial pilot is that you have to be prepared to fly into any airport that a client wants to fly into. Coming into McCarran would be good practice in case I ever needed to do it with a client on board. That, in fact, was another reason I’d decided to land there.

I’d decided to come in from the east, making my call at Lake Las Vegas. Lake Las Vegas is a relatively small lake created by damming up one of Lake Mead’s tributary washes. Some people blame that dam — at least in part — for the low water levels at Lake Mead.

I’d decided to come in from the east, making my call at Lake Las Vegas. Lake Las Vegas is a relatively small lake created by damming up one of Lake Mead’s tributary washes. Some people blame that dam — at least in part — for the low water levels at Lake Mead.

I flew up the west shoreline of Lake Mead, keeping an eye out for tour traffic and fiddling with my radio to tune in the ATIS for McCarran. I soon learned not only the weather conditions, but the special frequency for helicopter operations, which was not on the chart or in the taxi diagram. I tuned into that, glad that I wouldn’t have to deal with approach control. But I also tuned the standby frequency to the regular tower frequency, just in case I needed it.

The smog layer that blankets Las Vegas came into view and I could see the high-rise structures shrouded within it. The tower of the Stratosphere was most identifiable, really standing out on the horizon.

I was just coming up on Lake Las Vegas, about 10 miles out from the airport, when I made a tentative call. Up to that point, the frequency had been completely quiet and I was worried that it might not be the right one.

“Las Vegas Helicopter Control, helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima?”

A woman’s voice responded immediately: “Helicopter Six-Three-Zero-Mike-Lima, this is Las Vegas Tower. Squawk four-two-zero-two.”

“Zero-Mike-Lima is squawking four-two-zero-two,” I replied. I reached down to my transponder and punched in the numbers.

As I did this, a TV helicopter called in with a request to fly at a higher than usual altitude over the Strip. There was an exchange between the tower and that helicopter. Then the controller said, “Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, say request.”

“Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima is over Lake Las Vegas with November. I’d like landing at Atlantic.” Lake Las Vegas was my position. November was the identification letter of the current ATIS information; this told her I’d heard the recording and had current wind, runway use, and altimeter settings (among other information). Atlantic, oddly enough, was the name of the FBO where I’d arranged to park. It was located on the northwest corner of the field.

The response came right away: “Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, we have you on radar. Cleared to enter Class Bravo airspace. Landing will be at your own risk at Atlantic.”

“Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima is unfamiliar, so I might need a little guidance.” Unfamiliar is a magic word in aviation. It tells the controller that you’re not familiar with the area, airport, or landing procedures there. It puts an extra burden on the controller, because now she needs to provide some directions to get you where you need to be without messing up the other traffic.

“Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima are you familiar with the Tropicana?”

I knew roughly where it was, but I couldn’t pick out its tower from the other ones silhouetted in the smog. “Vaguely,” I replied.

“Okay, helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, proceed westbound for now.”

“Zero-Mike-Lima is going west,” I confirmed.

I checked my compass and adjusted course a tiny bit. I was heading right toward the Stratosphere tower — the easiest landmark in front of me.

Unfortunately, I was also heading toward the setting sun. It was about 4:35 PM — at least on my clock; Nevada is one hour behind Arizona this time of year — and the sun was low on the horizon. I’d neglected to clean the plexiglas of my helicopter’s bubble, so the dust particles stuck there were catching and holding the light. Although I had no trouble seeing all around me, I had to raise my hand and shade my eyes periodically to get a good look at my eleven o’clock position. Just a little something to add to the stress of the situation.

I was about five miles out when the controller said, “Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima turn heading two-six-zero.”

“Two-six-zero, Zero-Mike-Lima.” I adjusted my course from 270 degrees to 260 degrees. At this point, I was north of the east/west runways, so incoming traffic on those runways would pass on my left. I still couldn’t see the airport.

I should make a note here about a helicopter pilot’s ability to see an airport on approach. You need to understand that helicopters fly at a much lower altitude than airplanes. I was about 600-700 feet over the city. The perspective from that altitude tends to “hide” an airport behind buildings and other structures. The smog makes things worse and the setting sun in my face made it even worse. So although my GPS told me where the airport was and I had a pretty good idea where it was in relation to the skyline, I couldn’t actually see it.

After another mile or so, the controller came back. “Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima turn heading two-five-zero.”

“Two-five-zero, Zero-Mike-Lima.” I made another slight course adjustment. Now I was pointing right at the fake Empire State and Chrysler buildings of the New York, New York casino.

Another minute or two went by. The controller had been talking to other helicopters, none of which were anywhere near me. Then she said, “Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, Atlantic is on the north end of the 1/19 runways. There are no inbounds for those runways, so you’re clear to cross. Landing is at your own risk. Report landing assured.”

“Zero-Mike-Lima cleared to cross the runways and land.” By now, I could see the runways in question, primarily because a plane had just departed to the south from one of them. The ramp area looked big and wide beyond them. I was already down to about 200 feet AGL when I spotted the Atlantic FBO’s building.

“Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima, there’s a red and white 737 taxiing near the end of the runway. We don’t like helicopters to fly near taxiing airplanes.”

I spotted the plane right away. How could I not? “Zero-Mike-Lima will stay clear,” I assured her. That turned out to be more difficult than I expected, mostly because I was worried about his jet wash when I passed behind him. So I kept it high until he was really clear, then made a slow descent down to the ramp.

There was some confusion about parking. A girl who apparently worked there directed me to park beside a jet. I did. But before I could throttle down to idle, a van sped over and signaled me to follow him. I lifted off and followed him down the taxiway. He directed me to what turned out to be a helicopter parking lot quite a distance from their facility.

I throttled down again and started the cooldown process while the van waited for me and other helicopters came in behind me to park on the ramp. Then I remembered the controller’s request about reporting landing assured. I keyed the mike: “Helicopter Zero-Mike-Lima is on the ground.”

Discover more from An Eclectic Mind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great story. Please keep them coming.