Understanding what debt costs.

Last night, in the middle of the night, U.S. Senate Republicans voted in a tax bill that would add an estimated $1.4 trillion to the deficit over the next 10 years (per the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report). The bill was long with many handwritten amendments and no one was given enough time to read and comprehend the entire thing. There was no debate in the Senate; Democrats were not even allowed to ask for enough time to read it all. Despite all this, almost every single Republican voted in favor of the bill.

Democrats did not. I like to think it’s because they want to fully understand something they vote in favor of, which I double many Republicans did. Or perhaps they actually believed the data in the CBO and Joint Tax Commission reports, which both indicated that the middle class would be harmed by the bill for the benefit of the wealthiest of Americans — many of whom just happen to be the biggest donors to Republican candidate campaigns.

All politics aside, however. This blog post isn’t about politics. It’s about the financial impact of living in debt.

My Qualifications

Before I dive into the numbers, let me take a moment to explain what makes me qualified to write about this.

First, my education and early work experience. I graduated from Hofstra University with a BBA with Highest Honors in Accounting. From school, I went right to work with the New York City Comptroller’s Office — and no, that’s not a spelling error — Bureau of Financial Audit. My job was to audit various organizations that had contractual agreements with the City of New York. I started as a Field Auditor and, within two years, became a Field Audit Supervisor responsible for overseeing up to 13 auditors. When it became apparent that the only way to move up in the Bureau was for someone to retire or die, I moved into private industry. I wound up in the corporate headquarters of Automatic Data Processing (ADP) where I was a Senior Auditor and then a Senior Financial Analyst. I audited various divisions of the company all over the country and later crunched numbers for executives who needed numbers to say certain things.

Second, my own experience with debt. It happened right out of college when I got my first credit cards. It was easy to buy things so I did. Trouble is, I had a lot of credit cards and I carried a balance on all of them. After a while, I could only afford the minimum payment on most of those cards. And if there’s one thing you must know about credit card debt is that it will take years to pay off a credit card if you only send in the minimum payment every month. I learned this lesson the hard way. I was able to avoid bankruptcy by simply cutting up the cards, reducing my spending, and putting more money toward my balances until they were all paid off. These days, I only have two credit cards — one for personal use and one for business use — and I pay the entire balance in full every single month before the due date. (More on the amount of money this saves in a moment.)

Third, my second career as a freelance technical writer. Writing 80+ books gave me plenty of experience explaining somewhat complex topics to readers. Among my books are about 10 editions of Quicken: The Official Guide for Osborne/McGraw-Hill. We wanted a book that went beyond simple software how-to and actually provided good financial advice for readers. I wrote sidebars and created downloadable worksheets for readers to use to help them improve their financial situation. A lot of them dealt with debt. (More on this in a moment.)

So yes, I know a little about finance and debt and I have the skills to write about them. If you need to learn, read on and be educated. If you think you already know what I have to say, read on and let’s compare notes in the comments section that follows. Fair enough?

Debt Service

The online Financial Dictionary, has several definitions for debt service. I like the second one because it applied to both businesses and individuals:

The amount of money required to make payments on the principal and interest on outstanding loans, the interest on bonds, or the principal of maturing bonds. An individual or company unable to make such payments is said to be “unable to service one’s debt.” An example of debt service is a monthly student loan payment.

So let’s take that student loan payment as an example — especially since student loans are in the news so much these days.

I was fortunate; I only had to borrow $5,000 and I had 10 years to pay it off. My payments were about $60 per month. (And no, I won’t tell you how long ago this was.)

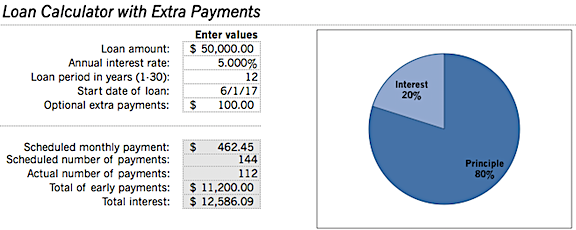

Let’s do the math on a more realistic modern example. Suppose you graduated from college with $50,000 in student debt. While there are many types of repayment plans, let’s go with a simple one: 12 years at 5% interest. This spiffy loan calculator template in Excel does all the math for you on monthly payments, and interest paid:

Not only does this Excel template calculate the amounts for a loan, but it charts the percentage of interest in your debt service.

In this example, your debt service for this loan would be $462.45 per month for 144 months. Over that time, you’d pay off not only the $50,000 you borrowed, but an additional $16,592.11 in interest.

Now imagine you have a Visa card that you just used to pay for a much needed — in your opinion, anyway — vacation to the Caribbean. You’ve got decent credit and the issuing bank gave you a $10,000 line of credit. But when you called to ask if you could raise that limit, they graciously popped it up to $14,000 — which is a great thing because you managed to charge up $8,459 on top of the balance you were already carrying for that big screen television you bought for the Super Bowl and last year’s trip to Hawaii. Now you’re looking at a balance of about $12,500. But when the bill comes, you’re relieved to see that the monthly minimum payment is only $273.33 per month.

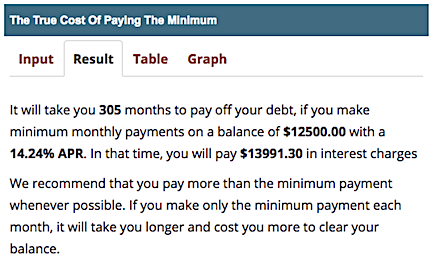

But let’s take a moment to take a closer look at the numbers. As this extremely helpful Minimum Payment Calculator explains, credit card companies calculate your minimum payment based on either a percentage of the balance or your interest plus 1%. (You can get the details for your credit card in the fine print in your bill or credit card agreement. You did read that, didn’t you?) For this example, I used the details for my Chase Amazon Visa card: currently 14.24% interest (tied to prime so it could change at any time) plus 1% of the balance plus any interest, late fees, or unpaid amounts due. If all that adds up to less than $25, then my minimum payment is $25.

The minimum payment calculator explains just why it’s so dumb to send in just the minimum payment on your credit cards every month.

Going a step farther with the math on this, you’ll learn that it will take 305 months to pay off the debt if you only pay the minimum payment. Why is that? Simple: each payment you make goes mostly to pay off interest so the debt is reduced at a very slow rate. If you stopped using that credit card and paid just the minimum payment every month for 305 months, you’d pay nearly $14,000 in interest on the original $12,500 debt.

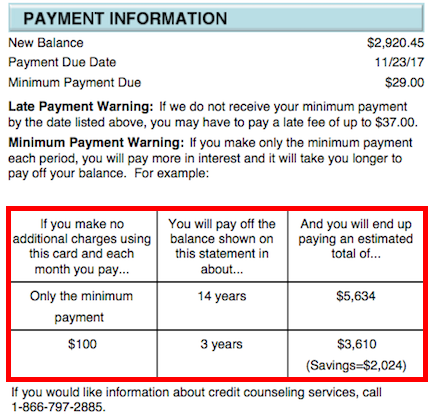

The CFPB — yeah, that’s the government agency that Trump says is hurting banks — added what’s in the red box to every credit card bill in an effort to educate consumers about credit card debt.

A side note here. Because so many people don’t understand this, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which was created during the Obama administration in part to help protect consumers from deceptive lending practices, began requiring credit card companies to make it clear how long it will take to pay off your credit card with just the minimum payment each month. Here’s an actual image from one of my Amazon Visa statements.

If you put all this together, you can see why it’s easy to get bogged down in debt when you have a bunch of credit cards and only send in the minimum payment. The debt never goes away unless you pay more than the minimum and stop using the credit cards.

Remember this: The money you spend on debt service is money you can’t spend on anything else. It should be considered mandatory spending, not discretionary. This is an important concept to keep in mind, not only for this discussion but for the way you manage your personal or business finances. The more debt you have, the less choices you have on how to spend your money. And the less money you’ll be able to save to get ahead.

Paying Down Debt

One of the things I recommended in my Quicken books was to pay more than what’s due on a debt — especially a large debt like a mortgage or a high interest debt like a credit card or consumer loan. That spiffy Excel template I showed earlier makes it easy to do the math. Suppose you pay an additional $100 per month toward that loan. Here are the results:

By sending in an additional $100 per month in this example loan, you can knock nearly 3 years off the term and save about $4,000.

Of course, it isn’t always easy to send more to pay down a loan. Maybe you can’t do it every month. But sometimes you can. Maybe you’ve sold a motorcycle you never ride for $1000 or got a $1500 holiday bonus. Or maybe this month’s commissions were better than expected. Send the extra money to a debt you want to pay down. It will make a big difference.

True story: When I was married, I was in charge of household finances. Whenever there was extra money in our joint checking account, I put that cash towards our mortgage. The result? We paid off our 15 year mortgage in 11 years, savings thousands of dollars in interest. (Yes, at the age of 50, I actually owned my home. And here’s a secret: I own the home I’m in now, too. Life is very good without a mortgage payment.)

My final piece of advice about personal credit is this: there is no reason to have more than one or two credit cards. Cut up the department store and gas credit cards. Get yourself down to just one or two MasterCard/Visa accounts. These cards can be used anywhere and some of them will earn you nice points or rebates. My Amazon Visa accumulates dollars I can spend on Amazon and, since I buy a lot of stuff there, I use them as they are accumulated. My AOPA MasterCard earns rebate dollars I apply to my account. Neither card comes with an annual fee and I pay balances in full every month so I don’t pay interest. This is free money, folks. It takes a lot of willpower to spend only what you can afford to pay off every month, but it is possible — I’ve been doing it for about 15 years now. Keeping your debt under control is the best way to stay financially secure when weathering unexpected hardships.

The Big Picture

What prompted this particular blog post is the news that the new tax plan will add an estimated $1.4 trillion (with a T) to the budget deficit. To understand what that means, let’s look at what a deficit is.

According to the Financial Dictionary, a deficit is:

A situation in which outflow of money exceeds inflow. That is, a deficit occurs when a government, company, or individual spends more than he/she/it receives in a given period of time, usually a year. One’s deficit adds to one’s debt, and, therefore, many analysts believe that deficits are unsustainable over the long-term.

(Again, I like that second definition because it applies to government, businesses, and individuals.)

Let’s look at an individual first. Supposed your take-home net pay is $3,000 per month. Every month, you pay $1200 for rent, $250 for utilities, $500 for groceries, $462 for your student loan, $100 for gas for your car, $80 for car insurance, $273 for your credit card-funded trip to the Caribbean and other stuff, and a total of $195 in payments toward your other credit cards. That’s a total of $3,060. Without even accounting for small miscellaneous expenses, pocket money, and the countless things I didn’t think to include here, you’re already running a $60 per month deficit. (Good thing your health insurance is a benefit that’s already taken from your paycheck; some of us aren’t so lucky and have to pay that out-of-pocket, too.)

So you increase your debt with cash advances or payday loans to see you through to the next month. Or maybe you’ve got some savings and you’re dipping into that to make up the difference. But eventually you’ll max out your debt and your savings will run out. What happens when it does? What happens when your monthly expenditures exceed income and you simply can’t pay what you owe anymore? Eviction, auto repossession, bankruptcy, homelessness. These are all possible.

This is the little picture — what happens when one person has a deficit. It’s easy to imagine it on a larger scale, like for a business. Think of a local retail business. The owner has to invest a bunch of money up front to set up the store with fixtures and get it properly decorated. He might have gotten a loan for that. Then more money to buy inventory. Rent, utilities, advertising, insurance. Then employees, with or without benefits but certainly with wages and employment taxes. He’s already at a deficit before he opens his doors. The business opens and he slowly builds a customer base. But what happens when/if revenues don’t cover monthly expenses? Or if a Walmart moves into town and half of his customers decide to shop there instead? More loans can help in the short term, but as the definition of deficit that I quoted above says, “many analysts believe that deficits are unsustainable over the long-term.” Of course they aren’t. When you spend more than you take in, you will eventually lose the ability to pay for what you’re spending.

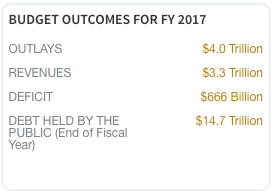

The CBO 2017 Budget numbers.

Now let’s look at the very big picture: the United States economy. The Congressional Budget Office has the numbers for 2017; the U.S. government spent $700 billion more than it took in for 2017. That means that the government added that $700 billion to its debt. And, according to the CBO, the country now has $14.7 trillion (yes, with a T) of debt.

(Suddenly, that $12,500 of credit card debt doesn’t seem so bad, eh?)

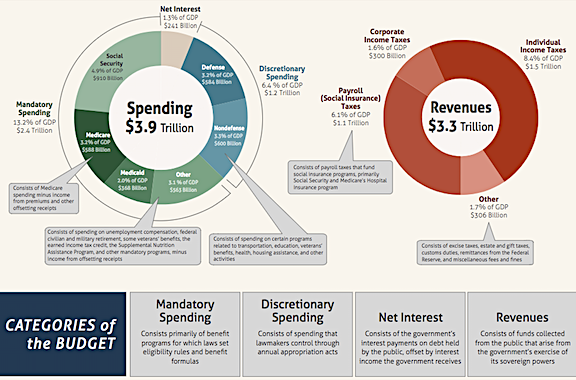

It’s hard to imagine $14.7 trillion in debt, but a few infographics show its impacts. First, here’s one from the CBO for 2016:

The CBO prepared this infographic for 2016. Can’t read it? Click here to download the big picture in PDF format.

I know it’s hard to read here — I had to reduce it to get it to fit in my blog page format. (You can download a PDF that’s easier to read.) What I want to draw your attention to is the number at the top of the chart on the left: Net Interest: $241 billion. So in 2016, the U.S. government spent $241 billion dollars on interest for its debt.

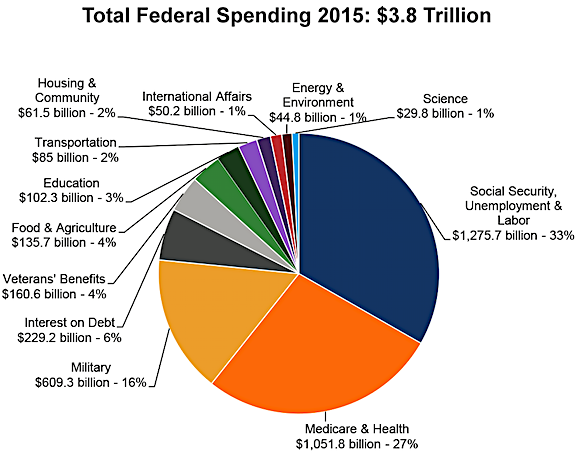

This next chart puts interest paid in perspective to various categories of spending. It’s from the National Priorities Project and is based on Office of Management and Budget (OMB) numbers for 2015. You can find it on the site’s Federal Spending: Where Does the Money Go page. I assume that this data is updated regularly, so if you’re reading this in the future, you may see different numbers. Here’s the spending chart that illustrates my point:

Here’s a breakdown of spending based on actual services provided. I think it’s tragic that the United States spends more money on interest for its absurd debt levels than it does for vital services that really can make America great again: education, energy, science, and food and agriculture, to name a few.

My point is this. Because we’re so deep in debt — and have been for a very long time now — we spend a huge amount of money just paying interest on our debt. That money could be going to education or health care or science. It could be doing so many things that actually benefit the American people — just like the interest on your credit card debt could be paying for a gym membership that might make you healthier or piano lessons that could develop your kid’s talent for music. Or any number of things that could make you or your family’s life better.

Why Are We Making this Worse?

These are the numbers. I know I’ve presented data from three different years, but it really doesn’t matter. We’ve been in this deficit/debt situation for a very long time now. Despite efforts to reduce the debt with a budget surplus as President Clinton managed to do during his term, the situation gets worse every year.

And now the Senate has approved a tax plan that will cut taxes for big businesses and the country’s wealthiest individuals, banking on a disproven “trickle down effect” to bring up the economy as a whole so more taxes can be collected. The CBO has already said that this budget will increase the deficit by $1.4 trillion over the next 10 years. Can we really afford debt service on that? What will we be giving up in order to pay interest on that debt?

Personally, I’m sick of Fox News-brainwashed right wingers complaining about Democrats increasing the deficit and debt. The truth is here for anyone interested in knowing it: the Republicans are even worse about budgeting. Last night’s ill-informed vote on a hastily prepared tax plan proves it.

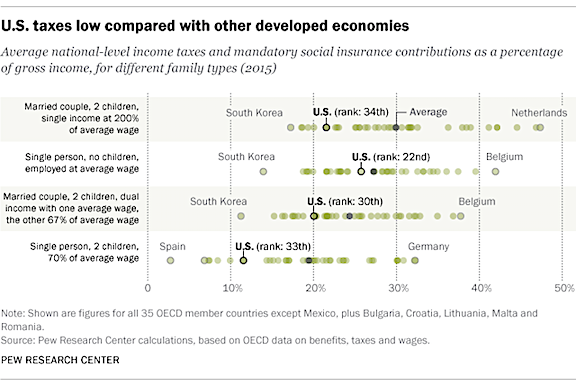

Americans already pay among the lowest tax rates for individuals in a developed nation. We pay taxes for a reason: to pay for the services we get. When my house catches fire, I want the fire department to show up. When I drive to Seattle or Portland or Arizona, I want to drive on smooth roads and cross bridges that won’t collapse. If I had kids or grandkids, I’d want them to go to a school where the teachers were well paid, happy, and effective. I want the FDA to make sure the food and medications I take are safe. I want the FAA to make sure the planes I fly in are safe and that pilots I share the sky with are properly trained and certificated. I want to be as proud of my country today as my parents were when we put the first man on the moon.

Pew Research study of U.S. taxpayer burden in 2015 compared to other developed nations. Get the details here.

None of this is possible without the revenue to cover the expenses of these services. Revenue comes from taxes. I’m willing to pay my fair share and I know that many others are, too. Why is that so hard for Republicans to understand?

As a fiscally responsible individual, I want this deficit budgeting to stop. Don’t you?

How can we ever expect our country to become “great again” if we throw away so much money on debt service?

It’s the percentages that are important here. Imagine a taxable income of $100K. 17.4% is $17,400. But 36% is more than double that: $36,000. Is it fair that someone with a taxable income of $40 million like Mr. Buffett, who gets to keep about $33 million of that after taxes, should be paying a lower tax rate than someone making $100K who only gets to keep $64K after taxes?

It’s the percentages that are important here. Imagine a taxable income of $100K. 17.4% is $17,400. But 36% is more than double that: $36,000. Is it fair that someone with a taxable income of $40 million like Mr. Buffett, who gets to keep about $33 million of that after taxes, should be paying a lower tax rate than someone making $100K who only gets to keep $64K after taxes?