Getting the hyper-local weather information I crave.

I’ve always been interested in weather. Yes, I’m the kind of person who’d leave The Weather Channel on all day as background noise — in the days when they actually broadcast live weather information all day. And always know the most up-to-date weather sources. And have multiple weather apps on my mobile devices so I could check one against the other.

My Thirst for Weather Data

Not long after moving into my Arizona home in the late 1990s, I bought a solar powered wireless weather station. My future wasband mounted it on the roof of the shed near the horse corral and it beamed back weather information to a panel at my desk. For a while, I had it connected to a Windows PC I had — the software wasn’t Mac compatible in those days — and put live weather information on a Wickenburg website I ran. In 2003, when I got the fuel manager contract at Wickenburg airport, we moved the weather station there — it was far more reliable than the ancient setup in use. (Wickenburg now — finally — has an AWOS.) When I sold the contract, I included the weather station among the assets of the business. For all I know, it’s still there.

Although I didn’t miss the weather station much as life dragged on in Wickenburg, I definitely wished I had weather stations in Washington where I spent my summers starting in 2008. I get seriously tuned into the weather during cherry season, checking radar throughout the day and always knowing the forecast — from multiple sources — for the next three days. I dreamed of having portable, Internet-connected weather stations with accurate rain gauges and webcams so I could place them at each orchard when it was under contract. You see, I fly when it rains and knowing exactly when and how hard it was raining would benefit not only me, but also my clients. Trouble is, orchards aren’t usually in places where Internet access is available and the cost of a 3G/4G/LTE connection for each station was prohibitive.

Fast-forward to the late summer of 2013. I moved to a 10-acre lot I’d bought at the base of the basalt cliffs in Malaga, WA — a place I like to call Malaga Heights. From my aerie, I could see the weather coming and going from the southwest to northeast. With a new home base, I started thinking seriously about a weather station again.

Weather Station Options

Technology had moved forward in the ten years since I last owned a weather station. The main thing I wanted was the ability to monitor weather from anywhere in the world on my cell phone. I had some practical applications for this, but it was mostly just a desire to get hyperlocal weather information, live, anytime, from anywhere.

I did some research. I discovered that weather stations fell into four categories:

- Basic home weather stations. These are the ones that put a panel in your house and one or more sensors outside that can broadcast data to the panel. I already had one of these — heck, I’ve had these forever. In 2013, when I was still living in my RV, it became extremely valuable for me to monitor temperatures during the winter at my water source and RV basement. But systems like these are extremely limited, not only in range but also in the available instruments. It’s usually just temperature, humidity, and barometric pressure.

- Weather stations with limited connectivity. These are weather stations that have a full set of instruments for temperature, humidity, wind speed/direction, and rainfall, but they just send that information to nearby information panel. That’s what I had back in the early 2000s.

- Weather stations with Internet connectivity. These are weather stations that have a full set of instruments for temperature, humidity, wind speed/direction, and rainfall, and they transmit data via the Internet, through wifi or a direct connection to a router. They often also transmit to a panel where the user can view data locally.

- Weather stations with Internet connectivity and direct smartphone access. These are weather stations that have a full set of instruments for temperature, humidity, wind speed/direction, and rainfall, and can transmit data directly to the Internet as well as to a smartphone app. Again, they also often transmit to a panel where the user can view data locally.

My main goal was to be able to view current weather conditions for my home on my iPhone. This would make it possible for me to assess conditions for landing my helicopter, which lives in my garage. When I fly home and put it away, I need to land on a 9×9 platform parked on my driveway on the east side of my home. With very strong winds in the area, landing there is difficult — so difficult that I prefer to land at a secondary landing zone on the north side of my home. I can then wait until the wind dies down, fire the helicopter back up, and move it to the platform. I don’t have to do this often — I think I did it just twice in all of 2015 — but it’s nice to know what to expect at home before I arrive. What’s interesting is that when the wind is howling at the airport across the river, it’s often quite calm at my driveway. This is likely because of my home being sheltered on two sides by terrain. That’s one of the reasons I built it where I did.

So at first it looked as if I’d need that last type of weather station — the kind with an app to get the data on my phone. Unfortunately, the stations I found that met that criteria were quite expensive — in the $250+ range. And I really couldn’t justify the expense, especially when I seldom have a real need for that weather data. After all, I only take the helicopter out about 50 times a year and the streamers on poles on my deck offer a decent indication of wind conditions when I get here. (I also have an airport-style windsock, but I positioned it too far from my landing zone to be of any real use to me. Long story there.) Maybe I was just trying to use flying as excuse for a new weather station? Probably.

More research showed me that Internet-compatible weather stations could usually be set up with The Weather Underground website. I started exploring stations already online there. I found one down at Crescent Bar, not far from one of the orchards I provide cherry drying services to. I clicked a link to get more information about the Weather station there and learned that it was an Ambient Weather WS-1400-IP.

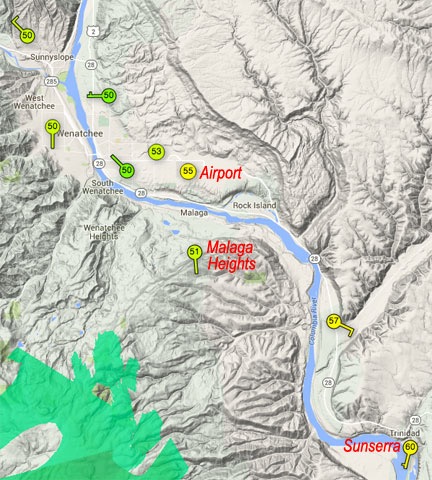

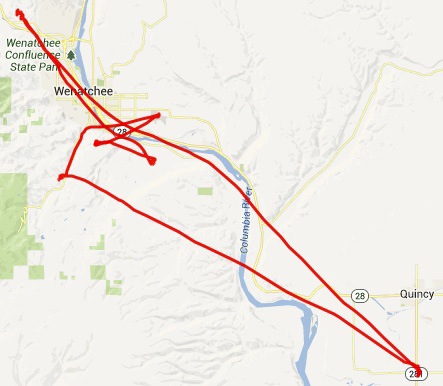

The WunderMap of my area shows the personal weather stations (PWSs) in the area. I’ve marked the one in Quincy and mine as well as the official weather station at the airport.

I did some more research and found that two Ambient Weather stations would meet my needs if I went with the Weather Underground: that one and the Ambient Weather WS-1001-WIFI. The difference: the more expensive ($299) WS-1001 had a panel to monitor the weather inside the house and did not require an ethernet connection to my router while the less expensive WE-1400-IP ($159) could only be viewed from a Web page or app and required an ethernet connection to my router. Both had the same basic set of instruments and were equally easy to mount. Both also had a solar panel to keep the station’s batteries charged.

The Ambient Weather WS-1400-IP includes outdoor weather instruments mounted together in one cluster; an indoor temperature, humidity, and pressure sensor; and an ObserverIP receiver that must be connected to a router. The iPad and iPhone in this marketing photo apparently indicate that data can be seen on mobile devices after registering the station with the Weather Underground.

I was fortunate in that I planned to mount the station at my shed, which was about 100 feet from my building. The line-of-sight receiver would go in the window overlooking the shed by my desk, which was less than two feet from my router. So as far as the connection went, requiring an ethernet cable was not an inconvenience. So the question was: Is the viewing panel worth the extra $140? My answer was no. I bought the WS-1400-IP.

Setting It Up

This mounting kit is perfect for mounting on the side of a building.

I wanted to mount the weather station on the side of my shed, preferably with all instruments above the sprinkler head I’d put up there for fire season protection. That meant I needed some mounting hardware. Rather than trying to rig up my own mount — and likely being frustrated every step of the way — I spent another $44 (with shipping) on the Ambient Weather EZ-30-12 Mounting Kit with Mast.

Assembling the weather station was pretty easy. All I had to do was attach the wind vane at the top and one of the two short mounting poles on the bottom. The crimped pole fit snugly into the top of the mast that came with the mounting kit. I added two batteries to the indoor sensor and set it on a shelf near my desk. I then connected the receiver’s DC adapter to an outlet and ethernet cable to one of the four LAN ports on my router. Done.

The next step was to register my PWS on the Weather Underground. The weather station’s manual provides the URL. I had to create an account and then provide some information about my location and the weather station. At the end of the process, I received a weather station identifier.

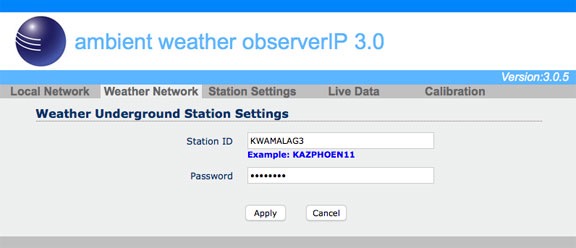

Next, I had to use the IPTOOL application on my Mac (a Windows version is also available, of course) to locate the weather station’s receiver on my network and connect. That opened a configuration page in my Web browser. I used that to enter the station ID provided by the Weather Underground, as well as my password on that system. I could use other settings pages to provide the station model number, time zone settings, and units of measure. The Live Data page showed a rather user-unfriendly table of data collected from the station.

The Weather Network configuration screen for my weather station lets me put in my Weather Underground ID.

Of course, since the weather station was still inside as I did all this, it registered inside temperatures and wacky wind readings as I moved it around. It was time to install it. I certainly didn’t want bad data going out on the network.

The weather station is positioned just slightly above my fire season sprinkler head. I’ll need to raise it (or lower the sprinkler head) before next fire season.

My timing was good and bad: it had turned kind of nasty and was about to rain. That was good if I wanted to record rain information (which I did) but bad if I didn’t want to be on a ladder in the rain (which I didn’t). Still, I went out to the shed and climbed on the orchard ladder with a drill and impact driver and all the parts I needed. Within 15 minutes it was installed, level and pointed the right way. It’s not quite as tall as I’d hoped; in the future, I’ll likely add a second mast pole to raise it another three feet.

The rain started before I was done. I admit I was tickled to see it registering in the Live Data screen when I got inside. (I am such a weather geek.)

There was one more thing I needed to do — although I didn’t realize it until the next day. I thought the weather station would automatically adjust the pressure reading for my elevation of approximately 1550 feet above sea level. But when I realized that the readings were significantly lower than what they should have been, I did some additional research to see how I could fix it. The answer was to enter a relative pressure offset amount in the Calibration page of the weather stations settings. To do this, I needed an accurate pressure reading. I waited until the automated weather observation system at the airport just three miles away across the river updated and calculated the amount of offset to enter. I plugged that figure into the right box, updated the settings, and was good to go.

Viewing Weather Data

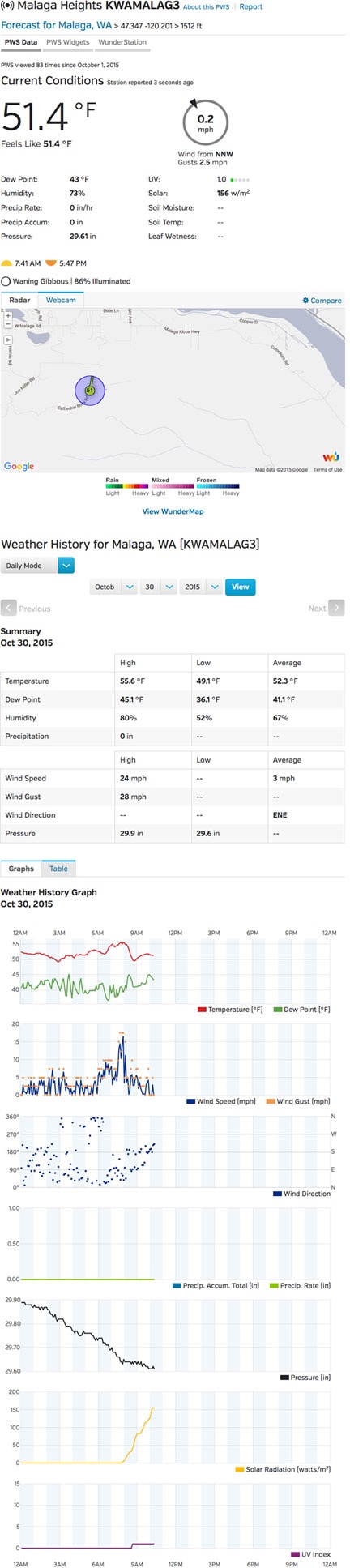

Here’s a snapshot of the display for my weather station as I wrote this blog post.

Although the Weather Underground claims it can take up to 24 hours to display a PWS on its site, mine was visible within an hour. It’s got its own page, which can be viewed by anyone at any time; I called it Malaga Heights. Here’s a screenshot of what you might see if you go to that link.

As you can see, there’s a lot of data, including current conditions pulled right from my PWS, sunrise and sunset times, moon information, and a radar map of my area. The current conditions are updated regularly; if you keep watching, you’ll see it change, especially if the wind is variable.

The weather history section summaries and graphs weather information for the day or a period you choose. As you can see, the temperature has been pretty steady on this overcast day, the wind really kicked up a few hours ago, and the pressure is falling. Solar radiation is likely measured for the solar cells on the station; it always rises after sunrise and drops back to zero by sunset.

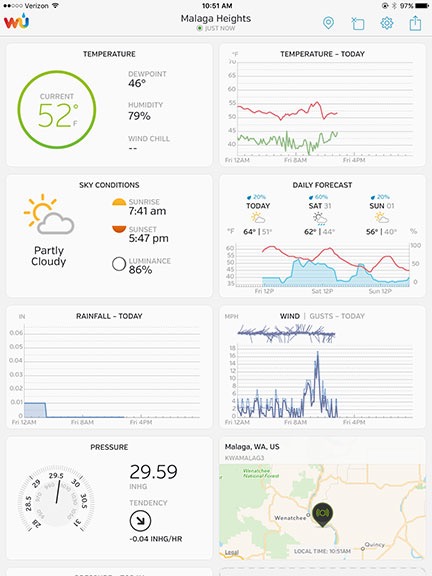

The WunderStation app on my iPad.

All of this information is also available in the various Weather Underground apps you can install on smartphones and tablets. For example, the WunderStation app on my iPad displays rearrangeable tiles of data that update automatically. I can even set up multiple PWSes in the app and switch from one to another with a swipe. Similarly, the Wunderground app on my iPhone displays information about any PWS, including my own. Both apps are free, and if you’re a Weather Underground member — a bargain at only $10/year — they’re also ad-free. (I hate ads).

But wait! There’s more! You can also install a “sticker” or widget on your website or blog. You can see the style I prefer at the top of this blog post; one that fits better in the sidebar appears at the bottom of the sidebar on every page.

What’s Next

Of course, all this is not enough for a true weather geek like me. The Weather Underground supports a PWS webcam.

I’ve had webcams on and off for years and would really like to have one here. After all, not only do I have an amazing view to share, but my view of the sky would clearly show weather conditions that would interest other weather geeks.

There’s always something new to add to a system, isn’t there?

The one that I know will be compatible with the system is the AmbientCamHD Outdoor WiFi WeatherCam. It has a few features I think I could use to create time-lapses. I’ve added it to my Amazon wish list, but I suspect I’ll likely break down and just buy it for myself before Christmas.

Some things I just can’t resist.

The National Weather Service at

The National Weather Service at  When rain is in the area or on the way, I use the

When rain is in the area or on the way, I use the  When I’m out and about and have access to the Internet, I use WeatherBug on my iPad to see weather information, including a radar graphic, forecast summary, and hour-by-hour forecast. I can also use its Webcam images to help judge visibility in the event that I need to cross the Cascades to get to Seattle. (Which I don’t usually do during the season.) WeatherBug is also available for mobile phones; I really do need to get it back on my BlackBerry.

When I’m out and about and have access to the Internet, I use WeatherBug on my iPad to see weather information, including a radar graphic, forecast summary, and hour-by-hour forecast. I can also use its Webcam images to help judge visibility in the event that I need to cross the Cascades to get to Seattle. (Which I don’t usually do during the season.) WeatherBug is also available for mobile phones; I really do need to get it back on my BlackBerry. The helicopter is a quarter mile away and already fueled and preflighted. All I have to do is pull off the blade covers. I can be airborne within 10 minutes of my client’s call. The orchard is a 4-minute flight from here. So I’d much rather sit in my nice warm RV, watching the weather on radar, than sitting out in my truck by the helicopter, blind without most of my weather sources.

The helicopter is a quarter mile away and already fueled and preflighted. All I have to do is pull off the blade covers. I can be airborne within 10 minutes of my client’s call. The orchard is a 4-minute flight from here. So I’d much rather sit in my nice warm RV, watching the weather on radar, than sitting out in my truck by the helicopter, blind without most of my weather sources. Jim is like me. He doesn’t take a lot of bullshit. He told them what they could do with their hangars and applied for a permit with Maricopa County to build a hangar and helipad at his house. In less than a year, he had a huge hangar on his 48-acre spread with a nicely marked and perfectly legal helipad out front.

Jim is like me. He doesn’t take a lot of bullshit. He told them what they could do with their hangars and applied for a permit with Maricopa County to build a hangar and helipad at his house. In less than a year, he had a huge hangar on his 48-acre spread with a nicely marked and perfectly legal helipad out front. We took off to the south, toward the airport. I’d brought along my video camera and Mike was using it to shoot images of the things we flew over. I’ve been wanting to get some good video footage from the helicopter for

We took off to the south, toward the airport. I’d brought along my video camera and Mike was using it to shoot images of the things we flew over. I’ve been wanting to get some good video footage from the helicopter for  We used to do aerial photography together with a Pentax 67 medium format camera. It was a pain in the butt. The camera could only hold 20 shots (I think), it weighed a ton, and although it did have an exposure meter, it didn’t have automatic exposure. That means the photographer had to adjust the shutter speed or aperture for every shot based on the meter reading. Mike didn’t like to do that. He’d set the exposure once or twice during the whole shoot. So half the pictures would be under or over exposed. Of course, the film couldn’t be processed in WIckenburg — we had to send it out. And we had to send out for enlargements, too. It was idiotic.

We used to do aerial photography together with a Pentax 67 medium format camera. It was a pain in the butt. The camera could only hold 20 shots (I think), it weighed a ton, and although it did have an exposure meter, it didn’t have automatic exposure. That means the photographer had to adjust the shutter speed or aperture for every shot based on the meter reading. Mike didn’t like to do that. He’d set the exposure once or twice during the whole shoot. So half the pictures would be under or over exposed. Of course, the film couldn’t be processed in WIckenburg — we had to send it out. And we had to send out for enlargements, too. It was idiotic.