I reboot my beekeeping efforts with two nucs in a new location.

I started beekeeping back in the spring of 2013. I’ve had mixed results.

Some History

I started beekeeping in June 2013 and have been blogging about it periodically. If you’re interested in reading the other posts in this series, follow the

Adventures in Beekeeping tag. Keep in mind that posts appear in reverse chronological order, with the most recent first.

I started with one colony in 2013, caught a swarm, and then split a hive to end the season with three colonies. That first colony yielded about 2-1/2 gallons of honey with an early harvest. I was very encouraged. Late in the season, I moved my hives from their temporary homes in Wenatchee and Wenatchee Heights to my new home in Malaga. I set up an apiary or bee yard for them not far from where I was living in my RV and would build my home.

I lost two of the three colonies over the winter of 2013/2014 but the surviving hive, which I took with me to California for two months, was strong and I split it early. When I returned home, I added four packages in April and caught a swarm, ending the season with seven hives.

Unfortunately, I neglected my beekeeping duties that summer — mostly because I was kept so busy with the construction of my new home — harvested another 2-1/2 gallons of honey very late, and failed to treat for mites. My neglect did not go unpunished: despite moving six of the hives to East Wenatchee for the winter to avoid the Shadow Time at home, all seven of my hives died.

Cleaning Up

I retrieved the hives from East Wenatchee on their trailer, opened the boxes, and took a look. All of the boxes were full of dead bees and a lot of mold. (Yes, I know: I should have ventilated the tops of the boxes. I did mention my general neglect, didn’t I?) I thought it was the mold that killed them, but later decided it was probably a general weakening due to mites, which I hadn’t treated for prior to winter. (Lesson learned.)

I started pulling out frames and scraping them clean, keeping the comb to melt down wax. Some of the frames I’d bought locally at Coastal Farm and Ranch had been improperly brushed with wax, resulting in irregular comb that was a real bitch to extract honey from. I was determined to rewax all of the frames bought from Coastal before reusing them and needed the wax stores to do the job. But with so many dead bees and so much mold, most of it wasn’t worth saving.

I surfed the net to find some info on cleaning mold out of hives. Several sources said to simply reuse the moldy frames — the bees would clean it up. One source even had a video showing a moldy frame put into a hive and that same frame, a week later, cleaned up and being used by the bees.

Many sources suggested freezing frames to kill any pests that might be on them. That’s easy enough to do — I have a chest freezer that’s big enough to hold a few dozen frames at a time — but since my hives were out in freezing weather after the bees died, I don’t think it’s necessary.

Meanwhile, on warm days — and we had a few of them last week — the neighborhood bees, most of which are likely pollinators brought to the area for cherry pollination, came by and cleaned out the remaining honey. For a few days, the area around that bee trailer was buzzing with thousands of “robber” bees. It took them about a week to clean up.

The pollinators are back! This orchard just off my street has blooming cherry trees and pollinator bees brought in just for the season.

I ordered four packages of bees from the supplier used by the beekeeping club I belong to: the North Central Washington Beekeepers Association. Unfortunately, they would not arrive until mid April.

I set up a hive box, base, and lid on the hive stand near my garden. That’ll be for my garden hive. And then I started to rethink where to put my new hives once I got them.

A New Bee Yard

I have ten acres of land here in Malaga. While about 30% of it is too hilly to accommodate bee hives and I’m using about 10% of it for my home, I still have several acres I’m not using. It seemed silly to put the bees so close to my home, in my view, when I could move them farther east on some land I wasn’t likely to use for anything else.

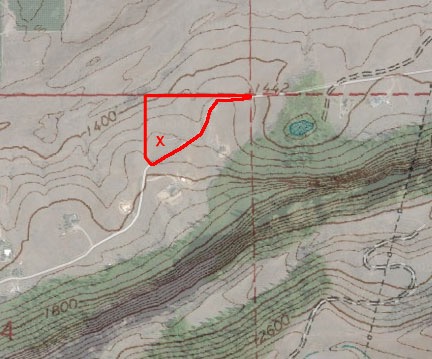

I threw together this hybrid topo/satellite map to show the lay of the land. The odd shaped red box is my 10 acre parcel; the south property line follows the road — hence the odd shape. The X is my homesite.

Understand that my lot has an odd shape. While its west and north boundaries run pretty much north/south and east/west respectively, its south boundary follows the road. Since the road winds northeast past my home, the farther you get on the east side of my property, the narrower the property is. At the very far east end, which is over a ridge and out of sight from my home, it’s only about 20 feet wide.

Before that point, however, right where the lot starts to get narrow, is a small ridge where my lot is about 100 feet wide. I know exactly where my property line is there because I had surveyors place a stake on the ridge back in 2013 before I bought the property. This is the easternmost part of my land that I can see from my home; I have to stand on that ridge to see beyond it. It’s also the part of my land that receives direct sunlight the longest.

I’d been considering that location as a site for my bee yard for a while and I drove out there a few times to take a closer look. The ground wasn’t exactly level and there were some sagebrush bushes, along with the bunch grass and wildflowers native to the area. But there were a few areas that were relatively clear and level and would be easy enough to get to with my ATV or Jeep or even the bee trailer. It would be a shame to carve in a two-track road with my tires, but it wasn’t as if the road would be long or I’d see it from my home. The ground was soft enough that I could probably even drive in a few T-posts, which I already had, and fence in the area to keep out large critters.

I let the information stew in my brain while I went on with my life.

Two Nucs from Wapato

I am not a patient person. The warm weather and abundance of wildflowers and orchard flowers were driving me nuts. If I had bees, they’d be out and about, visiting flowers, bringing home pollen and nectar, growing their hives. I could not only do a hive split in late May or early June, but I could probably even harvest some honey then — which was a good thing because I had less than a quart left.

Beekeeping 101: Nuc vs. PackageA nuc is a nucleus hive. It’s a cardboard box with an established queen and five drawn-out frames of honey and brood. It’s basically a small colony. You get it home, put the frames in a standard hive box with five empty frames, and the colony simply carries on, expanding into those frames you provided. This is the easiest way to get started.

A package is a box of bees with a queen in a cage. You dump the bees into a hive box filled with empty frames, put the queen’s cage between two frames with the cork replaced by a piece of candy or marshmallow, and cover up the box. The bees eat through the candy to release the queen and she starts laying eggs.

The main benefit of a nuc is that with capped brood already available, new bees will emerge from cells immediately; although a queen in a package should start laying eggs immediately, it’ll take three weeks for the new bees to start emerging.

So I started poking around, looking for bees. And I discovered that the Sunrise Honey Farm was selling nucs, with a pickup date down in Wapato on April 4.

To be fair, some people from my club had ordered nucs from Sunrise and they were delivered to Wenatchee the previous weekend. Somehow I thought the bees I ordered would arrive the same day so I ordered the packages, which were considerably less expensive. If I’d known that the nucs would arrive three weeks earlier, I would have gone with the nucs.

I did not want to drive to Wapato. It’s more than two hours away, south of Yakima. But I wanted an earlier start. So I called Sunrise and left a message. A few days later, they called back to say that they had a cancellation and there were two nucs available. I told them I’d take them. They told me to be in Wapato between 7 AM and 10 AM on Saturday.

I left home at 7 AM in my little Honda S2000 to make the drive. Along the way, I stopped down at Crescent Bar, where one of the cherry orchards I’m on contract to dry was in full bloom with bees on. I could not have timed it any better. When I arrived, the beekeepers were just pulling the last pallet of hives out of the orchard. I pulled over, rolled down the window, and chatted with the beekeeper, Eric, for about 10 minutes.

Wow. What an education! He told me that the cause of death in my hives was most likely nosema, although varroa, as I suspected, had probably weakened them, too. He recommended a product to apply at the end of honey harvest, before winter. He also suggested that I feed pollen late in the season when food sources were scarce. He said that doing these things should keep the bees strong enough to get through the winter.

I drove the rest of the way along a scenic route that took me along the Columbia River and then through rolling hills studded with farms and orchards. After a quick bathroom stop at a gas station five miles short of my destination, I pulled into a farmhouse driveway where I flatbed truck waited. It was just after 10 AM and there were just two nuc boxes on the truck’s bed.

I apologized for being late and they told me I was right on time. I gave them money and we loaded the two boxes into my car’s trunk. They didn’t fit, of course — my trunk needed to be about two inches deeper. So we used Penny’s dog leash to tie the trunk lid down. (Note to self: put bungee cord in Honda trunk.) We said goodbye and I headed home to Malaga; they headed back to their home in Spokane.

Hiving My Nucs

At home, I took the nucs out of the trunk and put them in the shade. One of them was buzzing loudly; the other was more subdued. I put the car away.

I was very pleased to see that the new nuc boxes were solid. In the past, I’d gotten boxes that the bees could escape from; it didn’t seem as if any were escaping from these.

It was only about 1 PM so I had plenty of time to get the bee yard set up and put the bees in their hives. Or at least I thought I did. The weather made me doubt that.

I used my ATV with its farm trailer attached to move a pallet, and several blocks of scrap wood posts, a level, and the beehive bottoms and tops out to where I planned to put the bees. As I suspected, I could drive the ATV right up to the yard area. I set up the pallet on the blocks, raising it about 8 inches off the ground. I was able to get it surprisingly level. I set up the hive bottoms and checked the level again. One rocked a bit; the pallet wasn’t perfectly flat. Some Pergo scraps under a corner would fix that. I positioned them on half the pallet, leaving room for two more hives. I’d have at least six by month-end.

On the second trip, I brought out the hive bodies with five relatively clean honey and brood frames in each.

By that time, the wind was blowing cold and hard. There was a storm moving in from the south toward Wenatchee. It might even be snowing up on Mission Ridge. Although it looked as if the storm might miss my place, who knew? I didn’t want to be out there with open beehives in a cold wind or rain. So I took a break and went inside for a while.

A friend called. He was in the area and asked if he could drop by. Of course!

We chatted, drank hard cider, assembled two of my three new bar stools, and tried them out. The storm never came. The sun came out and the wind died down. I kept thinking about my bees, eager to get them put away before nightfall. But I was enjoying my friend’s company. Still, when he said he had things to do at home, I didn’t stop him from leaving.

By that time, it was 5 and the sun was getting low. The wind had kicked up again, but not as bad. I loaded the bees, my smoker, and my hive tool into my Jeep. I suited up in my bee suit. Then I drove out to my new bee yard, backed the Jeep into the yard, and got to work.

I did one nuc box at a time. They were both filled with old, propolis-stained brood frames, with many capped brood cells. I didn’t waste time examining each frame or looking for the queen. In both cases, however, I did notice a queen cage fastened to a frame; I’ll need to make sure there’s no queen in each cage before removing them.

I used my ATV with its attached farm trailer to bring the hive components out to the new bee yard. There’s a lot of balsamroot in the area.

I have to admit that I’m a bit disappointed. Apparently, these nucs were created by taking brood frames with bees on them from the pollination hives and adding a caged queen. This is like a mix of a nuc and a package — the only thing that makes it better than the package is the inclusion of capped brood. The queen isn’t really “established;” she may not even be laying eggs yet. I need to examine the frames more closely on a warm day to see what’s going on.

Of course, some of the bees were left behind in the nuc boxes. That’s common. I left the boxes in front of the hives with rocks in the bottoms so they wouldn’t blow away if the wind kicked up hard again; the straggling bees might find their way into the hives. Or they might not and simply die overnight in the cold.

I realized belatedly that I should have fed them but I didn’t have any feed ready; I prepped some later when I got back in and put feeders at each hive this morning, before it warmed up. I also picked up the nuc boxes and put them away; they’ll come in handy if I have to capture any swarms over the next few months or if I want to do a hive split.

My bees are within sight of my home — and Mission Ridge, which is still snow-covered.

This Year’s Plan

I’ve decided to be a good and dedicated beekeeper this season. That means doing a hive inspection every 10 to 14 days, keeping copious notes about hive conditions, using integrated pest management, and making sure my bees are well fed and healthy before winter. I can’t use hot weather as an excuse to avoid a trip to the bee yard — I bought a vented bee suit at Mann Lake when I was there last month. I’ll also harvest honey on a more timely basis — as I learned last season, a late harvest is not fun.

I’m also working on some plans to put my bees in other locations, including a resort about 40 miles from here. If I get the resort contract, I’ll do some beekeeping seminars for resort guests when I do hive inspections there, thus earning some additional revenue to support this “hobby.” And that’ll open up a whole new market for honey sales.

I’ve already decided that if I have another total loss winter, I’ll give up as a beekeeper. But I think that if I do what I need to do to keep my bees healthy, I’ll have enough colonies next spring to continue without another bee purchase.

Wish me luck!