15+ hours of cherry drying, hop rides, and horse roundup in three days.

My new old helicopter, Mr Bleu, had a lot of time to rest after our flight up from Arizona to Washington in April. Too much time, if you ask me. I did a 2-hour photo flight one day not long after I brought it home and then a handful of hour-long tours of the area for locals and tourists. I took it down to Cave B Winery for lunch with some friends and to pick up my wine club shipment. And I ran it over to the airport once for a bit of maintenance. But other than that, it’s been parked, mostly waiting for cherry season and my big June event.

Cherry Season

The work that pays my bills every year is cherry drying. I started doing this way back in 2008, making this my eleventh season.

I’ve blogged about this extensively since I started, so if you want details or more information about cherry drying, use the search box to search for “cherry drying.” Then read what comes up. Or watch this surprisingly popular video or this more informative video I made.

The short version is that cherry growers hire helicopters to stand by during the last 3-5 weeks the cherries are on the trees. When it rains, we fly low and slow over the treetops to blow the water off so the cherries don’t split. It’s slow, tedious, and often dangerous work and very few pilots do it more than one or two seasons before they find more interesting things to do. But I’ve stuck with it and built up a bit of a reputation based on consistent customer service.

My business has grown over the years. About seven years ago, I started getting more contracts than I could handle alone and began hiring pilots with helicopters to work with me as a team. Every year, I have a few core guys I can turn to and a number of slots that are filled with different guys every year. Last year was tough — although I had a lot of acreage to cover and six pilots with helicopters to join me, it didn’t really rain. That turned off a lot of guys who thought they’d make big bucks. The previous year was the opposite; it never seemed to stop raining and we flew more than I thought possible.

That’s how it is, though. As I tell my crew, the only thing you can count on is the standby pay; if you can’t make it work financially with just that, you shouldn’t come.

This year, I have a small team: there are just four of us. I started on June 1 with the other guys joining me as my acreage load picked up. One guy started June 15, two more will start tomorrow. Then, as cherries are picked and the acreage load drops, the pilots will leave and I’ll finish up alone. As of now, I should be done by August 11.

I work mostly with R44s, but this year we have a Bell 206L with us, too. (Last year we had an S-55.) They’ve been pulling out a lot of acreage in my area due to small cherry virus so I lost a few contracts for that. And since last year was so dry, a handful of growers and orchard managers decided to skip helicopter coverage and toss the dice with Mother Nature. There’s always crop insurance to prevent a total loss.

Contrary to what a lot of people seem to think about the entire state of Washington, it isn’t all as rainy as Seattle. I live on the east side of the Cascade Mountains which is desert-like. In fact, I’d say our climate is almost identical to Flagstaff or Prescott, AZ. So we have a lot of sun and, without irrigation from the Columbia River, which flows right through the area, we wouldn’t have orchards or farming.

I did some flying the first week I was on contract. On Friday afternoon, I took two pilots out to see the orchards that were going on contract within the next few days. Then, on Friday evening, with one pilot just settling in after his flight up from Mesa, AZ, and another already on board and prepped to do a handful of local orchards, it rained again. I launched at 8:15 PM. I only had 20 acres of bings to dry, so I was able to get the job done before sunset, which is at about 9 PM this time of year.

That turned out to be the first of many cherry drying flights that weekend.

Here’s Mr Bleu at its temporary home after Friday’s last flight.

The Big June Event

On the Saturday before Father’s Day every year, Pangborn Memorial Airport in East Wenatchee holds its big Aviation Day event. There are static displays of airplanes and helicopters, informational booths manned by Alaska Air and other aviation-related companies, a fire helicopter rappelling demonstration, and, of course, helicopter rides. I’ve been doing the rides with my cherry drying crew for the past six or seven years.

One of the planes on display was this beautiful DC-3, which I got a chance to photograph both inside and out on Thursday and Friday. (Blog post to come.)

This is a huge rides event for us. After all, how often can a helicopter company fly non-stop all day long with three helicopters giving rides? Honestly, I think that if we had a fourth helicopter on the team, we’d still be flying all day.

We had a good ground crew this year. With three people on that crew — one to sell tickets and two to handle safety briefings and escort passengers to and from the helicopters for hot loading — the pilots never had to wait more than a few seconds after touching down for the passengers to be swapped out. The quick turn time is vital for maximizing the number of rides you can do and keeping passenger wait times short.

Part of the equation is also making sure the pilots space themselves properly so there’s only one helicopter on the ground at a time. The rides we 8 to 10 minutes long so even with three helicopters, there were a few minutes between each landing. Any time one of us looked like we might land before the one ahead of us departed the landing zone, we slowed up to improve spacing. It worked like a charm.

And it should. The three pilots doing the ride had a lot of aviation experience. I’ve got about 3700 hours in helicopters and have been flying for about 20 years. At this point, I must have done close to 100 rides events. Woody, who retired from American Airlines in March of this year, has over 30,000 hours as a pilot and is a partner in a flight school that also does rides at events. And Gary, who owns and operates a fleet of helicopters at a flight school near Salt Lake City with his wife Lorri, has probably done even more rides events than me. Lorri is, by far, the best ground crew manager I’ve ever worked with.

Our three R44s, parked on the ramp later in the day, after the event. Oddly, all three are blue.

More Cherry Drying

The forecast for Saturday called for rain. Some forecasts said 50% chance, others said 80%. The rain came in the form of fast-moving storms that seemed to come up out of nowhere and blow through the area. I really thought it would impact our passenger count, but there were always people waiting to fly. We just adjusted our tour routes to avoid flight in the areas where the rain was pouring down and the wind was howling. I was actually surprised at how easy it was to work around the weather.

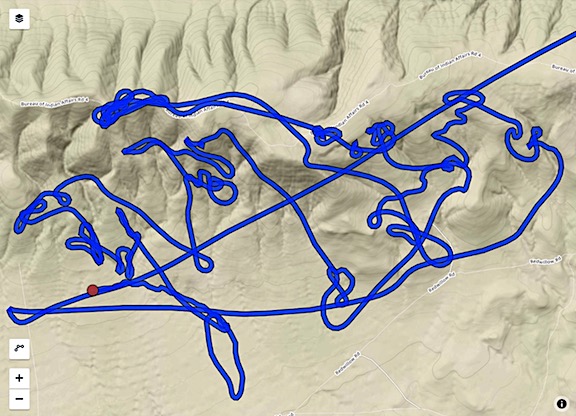

ForeFlight kept track of some (but not all) of one of my afternoon cherry drying flight. Fun stuff, eh?

Of course with rain came calls to dry cherry trees. They were evenly spaced. I took the first one since I was prepped for it: 34 acres of mostly bings and Rainiers up a canyon about 7 miles from the airport. While I flew over the trees, Woody and Gary kept doing rides. I heard them on the radio making their position calls as I flew back and forth blowing water off the trees.

I was just finishing up when the second call came. Since Gary was prepped for that orchard, I put him on it and I went back to doing rides with Woody. By then, the wind had shifted and we reversed our tour direction. With more rain over downtown Wenatchee, we flew mostly over Malaga. That was kind of neat because we passed close enough to where Gary was working for my passengers to see him. On one tour, I even circled the orchard to make sure he knew where the Rainiers he was supposed to dry ended and the bings they didn’t want dried began.

He finished up, refueled, and joined us for rides. That’s when another grower called. This time, Woody was prepped for the orchard so I sent him while Gary and I kept doing rides. By then, the event was winding down and, as usual, the only crowd of people around was the crowd at our landing zone. Lorri stopped selling tickets and, by just after 4 PM, we took the last group. Gary and I set down near the landing zone. Our ground crew loaders left, we packed up our gear, and we went into a hangar where Century Aviation was displaying two antique aircraft it was restoring for clients. Woody joined us a short while later.

My friends at Century Aviation have restored the sole remaining Curtiss Flying Boat in existence. I’ll be the photo ship for its first test flight next month at Moses Lake.

Between the three of us, we’d flown 12.4 hours of rides flights and another 5.2 hours of cherry drying flights. Needless to say, it was a good day.

More Storms, More Wet Cherries

We all refueled and headed back to our parking areas. I’m based at a neighbor’s landing strip, Gary’s based at an orchard nearby, and Woody is based at a client orchard. We met up back at my home where Garry and Lorri are staying in their RV and Woody is staying in mine.

We were just talking about dinner when my phone rang again. This time, a client in Quincy was on the line. Although his contract didn’t start until the following Friday, a big storm had come through Quincy and he was wondering if he could have his cherries dried off contract. Since Gary was the guy who’d be drying his orchard when the contract started, I put it to him. Sure, he said. And he drove off to return to his helicopter. Fifteen minutes later, he did a flyby on his way to Quincy, which was 15 air minutes away.

I snapped this shot of Gary as he flew by enroute to Quincy. I suspect there will be a lot of helicopters flying by my home this summer.

Woody was getting ready to put a rib eye steak on my grill when we both noticed the storm clouds to the east, right where Gary had gone. A few minutes later, he called to say that he’d hit weather and had made a precautionary landing in a field. I checked radar and saw a huge cell right over the orchard he was headed for. Putting radar in motion showed me it was heading our way.

When the storm hit, it hit with a vengeance. Honestly: I have never experienced such wind and rain at my home. Because it was coming from the east, it even blew water under the door to my deck at the front of the house. Poor Woody had to go out and turn his steak on the grill with a towel draped over his head.

The power went out, came back, went out, came back with some flickering, and then went out again. It stayed out.

I knew the calls would be coming, so I headed down to Mr Bleu, leaving Woody to gobble down a beautiful steak and some salad. I parked in my truck near the helicopter and turned off the engine, leaving the radio on. It poured on me. My neighbor drove up and parked beside me. We rolled down our windows and chatted. He told me he needed to spray his apples and was hoping to do it that evening, but with all the rain, he’d have to wait. We chatted about a few other things, including my asshole neighbor who no one in town seems to like. The rain stopped. My phone rang. Five minutes later, I was in the air, heading toward one of the orchards on my list.

Meanwhile, Gary had made it to Quincy and was drying 50 acres of very wet cherry trees.

A call came in for Woody’s orchard and I told the owner that Woody was on his way.

I dried an 18-acre orchard, then zipped across the river and dried another five-acre orchard. The owner of the orchard Woody was drying asked if Woody would do one block again when he finished. I passed on the request via radio and Woody immediately reminded me that it would be dark soon and there were wires in the block the orchardist wanted dried. I told him to do whatever he felt comfortable with. (We didn’t know then, but another pilot had crashed after hitting wires farther upriver. She’s okay, but the helicopter is out, at least for the season.)

Another call came in for five more acres close to my home. By that time, it was getting dark and the wind was kicking up. I started to dry those last five acres but soon had trouble maintaining control in a gusty wind. Another storm was coming through. I decided to break off for safety’s sake. Maybe Mother Nature would do my job with the wind.

It was a good thing I stopped when I did. The wind was howling all the way back to my landing zone and, although it was light enough to see, it was darker than I like it to be when I’m working low-level. I managed to set Mr Bleu down in its parking spot. I cooled down the engine and shut down just as it started to rain again.

The power was still out at home. Woody had landed safely and was on his way back in my Jeep. Gary texted to let me know he was done but he had run low on fuel. Lorri was on her way over with their truck and fuel tank. It would be a 40-minute drive each way for her. Meanwhile, Malaga was still dark from the blackout, although Wenatchee and East Wenatchee seemed unaffected. I later learned that lightning had struck a transformer in the area during the first big storm of the evening. When Gary flew past on his way to his landing zone, I got back in my truck to go pick him up since I knew it would be at least 30 minutes before Lorri returned.

I shot this photo from my deck at about 9:30 Friday night. The power was still out in Malaga.

It was 10 PM by the time the helicopters were all tied up for the night and the pilots were back at base.

But I’d already begun getting calls for the next morning. We all knew we’d be up by 4 AM.

Drying at Dawn on Sunday

I was up at 3 AM. At exactly 3:56, I got a text from one of my clients asking me to dry his five acres in East Wenatchee again. I already had 48 acres lined up for Gary and 28 acres lined up for me.

I dropped Gary off at his helicopter on the way to mine. He launched at 4:40; I was five minutes behind him. I finished the first five acres before dawn and was nearly done with the second five acres when the sun broke over the horizon.

It was a beautiful day and I said as much over the radio. A guy in the ground crew at Pangborn Airport, checking the runway for FOD before Horizon’s 5:30 AM flight would depart, replied “Why wouldn’t it be?” Gary’s voice came through next: “It sure is.” I shared another piece of wisdom over the radio on my way to the 23-acre orchard waiting for me: “Any morning you get paid to fly is a beautiful morning.” Someone double-clicked a mic button in agreement.

I’d forgotten my sunglasses and cap, so I had to deal with the low sun shining in my face while I dried the parts of the orchard that were already in sunlight. No big deal; I’m used to it. The trees weren’t that wet and I was able to finish the job quicker than usual, saving the owner some money.

I was done and back at my base before 7 AM.

Here’s Mr Bleu parked in its landing zone after Sunday morning’s cherry drying flights.

Herding Horses

I wasn’t done flying for the day, though. I still had a big job ahead of me: herding horses on the Yakama Reservation south of Yakima, WA.

I went home, took a shower, had a second cup of coffee, and made breakfast. At 8:30 AM, I was back in my helicopter, climbing out past my home to get some fuel at the airport.

While the fueler did his job, I rigged up one of my GoPros, hoping to capture some footage of my flight down to Yakima, the work I did there, and my flight back. Although I used to mount the camera on the outside of the helicopter, the local FSDO wasn’t happy with my setup so I had to mount it inside the cockpit bubble. I had a solution with a suction cup mount and it worked good enough, although it wasn’t ideal. I was able to get it plugged into the intercom system so I’d have audio in.

If you’re wondering why they bother to move the horses, the answer is pretty simple: with no predators and decent grazing in the spring, the wild horse population booms. (I think I saw at least 300 horses in this one area of maybe 20 square miles that day and I know there are a lot more in the hills to the south.) Soon, the horses have devastated the grazing area, leaving nothing for them or any other animal — including the cattle that the Yakama nation depends on for its own food — to eat. As winter comes, these herds begin to starve to death.

While we all love the romantic idea of the Wild West filled with herds of wild horses, the overpopulation in some areas is a serious problem for both the horses and the people who are trying to live on the land.

When I asked what they do with the horses, I was told that they put them up for auction. I think it’s a hard sell; it’s unlikely that the adult horses can be trained to work on ranches or do horseback riding. The colts and fillies, however, have a chance at being trained to serve a useful purpose and would likely be bought by someone who would keep them alive.

I didn’t dwell on this aspect of the work I was doing. I recognize the problem and want to be part of the solution. I believe, however, that the best solution would be to try to limit reproduction. I believe that a better solution would be to somehow introduce birth control into the herd. Ideally, if possible, it could be done by darting from a helicopter. I’m assuming there’s some reason — technology? availability of drugs? cost? — that they don’t use an approach like this.

It would be sad if the problem got as bad as the wild pig problem in Texas — they shoot those from helicopters and leave their carcasses for scavengers.

I started back up and pointed the helicopter south, climbing steadily to clear the cliffs behind my house along the way. I had a nice little tailwind and did the 52 NM flight in less than 30 minutes. On the ground, I had the fueler top off both tanks and went inside the FBO to wait for a passenger. He was a no-show, but my client had texted me GPS coordinates to meet him. So when it became certain that my passenger was not going to show up, I climbed back into Mr Bleu and flew another 12 miles southwest over a ridge to a flat area in the middle of nowhere.

On the way, I saw a herd of about 20 horses on the south side of that ridge.

I was over the coordinates wondering where my client was when I suddenly saw him and two other people standing on a two-track road. The truck they’d come in was hidden out of sight behind a small rise. I landed on the road, cooled the engine, and shut down.

I met Troy, his nine-year-old son, and his cousin or nephew — I can’t remember which. We talked about what had to be done — get the horses that were up on the ridge down into the flat area and up against the fence and drive them up into the trap. I asked where the trap was and Troy just pointed up the road beyond the truck.

Meanwhile, they were looking out to the west where other wild horses were being driven into other traps by other members of their party: Troy’s father, brother, cousins, and nephews. I could barely see the activity — it was quite a ways off. We’d start off working separately and then maybe help them.

I gave Troy and his son a safety briefing and loaded them into the left side of the helicopter where they’d be able to see the same thing. I didn’t discover until later that it was Troy’s son’s first time ever airborne. (Please, parents, don’t introduce your kids to aviation on an animal roundup flight.)

We took off to the east, heading slightly north to the ridge I’d come over. I assumed he wanted to start with the herd I’d seen, but he wanted to go farther east than that. I’d estimate we went at least three to five miles from our starting point. He instructed me to go up a sort of canyon in the hillside with the idea that we’d get beyond whatever was up there and start moving them west.

It didn’t take long before we started seeing horses. A lot of horses. Maybe 15 or 20? Mares, colts, fillies, and always at least one stallion. I descended and moved in close from one side and, as I expected, they began running. I stayed behind them, just far enough off to keep them running without scaring them to death.

I could try to give you a play-by-play of the movement — after all, the video camera was running for most of the time and both Troy and I were talking — but do you really want to read it? I wouldn’t. Although it was sometimes a bit of a rush to fly, it wouldn’t make good reading. I basically had to keep the horses moving southwest down the ridge and into the flats. I did this by flying low behind them, moving right or left to “encourage” them to go the right direction.

Troy captured this image of me at work with a herd of horses up near the top of the ridge.

When Troy was confident they were going the right way, he’d instruct me to go back up and find another herd. It seemed that he wanted to gather all of the horses together into one big herd and get them all moving southwest toward the trap. So we went up and found another herd and started driving them down. And then another. And then another. And then we’d come up for a look to see where they all were and go back down to get the ones who were wandering back in track.

ForeFlight kept track of part of my first horse herding flight. Can you understand why a kid on his first ever fight might get pukey?

This went on for at least an hour. In the back seat, Troy’s son got sick — how could he not, considering our motion? — and I was very glad that Mr Bleu’s previous owner had left a barf bag in the front passenger pocket.

At one point, we had about 100 horses all in one big group following their established horse trails west in the foothills of that big ridge. It was a beautiful sight.

Little by little we got close to the trap, which I still hadn’t seen. A lead group of horses peeled off and started going back up the ridge. Troy told me to move the back down. I was working on it when he said, “Too late. They’re past the trap.”

What trap?

Here’s the second herd we tried to herd into Troy’s trap. This is a screen grab from my GoPro; it gives you an idea of the kinds of attitudes required for this work.

We went after another herd and had better success. I kept them south of an imaginary line only Troy could see and then moved them west to the fence line. That required me to jump a small power line and pick them back up on the other side. Once against the fence, Troy had me move them north without letting them move east. I drove them as he instructed, going only close enough to keep them moving. They followed a road and I suddenly began seeing red ribbons tied to the sagebrush. And then old wooden beams. A corral.

They got right up to the entrance of the corral, saw what was up ahead — a dead end — and stopped. For a moment, I hovered about 20 feet away from them and they all looked at me. It was a sort of standoff. Then I inched forward. They turned around, ran into the corral, and Troy’s cousin/nephew pulled a tarp across the entrance to trap them inside.

My camera didn’t capture this — Troy had accidentally disconnected its power about 20 minutes earlier — but Troy’s cell phone camera did.

Here’s the moment when the horses finally ran into the trap.

We went back down the road and I landed. I wanted Troy’s son out before he puked again and messed up my nearly new carpeting. (Mr Bleu might need an overhaul in 200 hours, but its carpet was obviously replaced just a short while ago and is in excellent condition.) I also wanted a closer look at the trap which, in my mind, wasn’t very big or sturdy. So we got out and walked up to where Troy’s cousin/nephew was attempting to get the horses to move from the “big” capture area to a much smaller holding pen.

We’d caught four mares, who of which might be pregnant, a colt, and a stallion. While the two guys worked the horses, the stallion got excited and jumped the fence. That left a total of five horses.I didn’t think that was very good — especially when you consider the 100+ horses we’d been moving all over the area — but Troy seemed happy enough.

Here’s a shot of the five horses we ended up with in the smaller holding pen.

I was ready to go get some more — I wanted them to get their money’s worth — when Troy got a call from someone working the other horses west of us. They needed help. So he and I got back on board, leaving his son with his cousin/nephew, and headed west.

There were more horses there and a lot more guys working them. Two guys on horseback, one guy on a dirt bike, and a woman in an SUV. There was a herd of about eight near the mouth of one of the traps and they wanted us to help them get it in. I got into position and started moving them with the vague idea of the trap being in a patch of woods. The horses got close, saw the trap, and broke into two groups. I went left and moved that group back toward the others. Then Troy told me they’d missed the trap and we’d get them in the next one.

The next one was at least a half mile away. I moved the horses along the top of the ridge and then down a hillside to another patch of woods. The dirt bike came into view and herded from the left as I moved them from the right. Together, we funneled them down to where a two-track road went into the woods. The dirt bike pulled up quickly — I couldn’t get close because of the tall trees. A moment later, the rider was off the bike closing the trap. I caught a glimpse of a bunch of horses in the woods there and Troy told me they’d already caught some. They now had 15 in that trap.

He guided me around to the west to find a few more herds. We spent another 30 minutes driving them down one ridge to the flats and then to the east where we had to drive them up another canyon. At one point, we were driving a herd of about 30 horses toward the trap. He got a call and we broke off to help them move another bunch of horses that they were working near the trap.

Of course, although I’d topped off both tanks in Yakima I’d also been flying almost nonstop for hours. My helicopter’s endurance is roughly three hours and we we’d been flying for about two and a half. I told Troy we had about 20 minutes until I needed to refuel. He understood and he told me that he’d only been cleared for a total of four to five hours of flight time. With the 90-minutes estimated round trip to get to him, our three hours in the air was all he could do.

We worked the large herd of horses near the second trap for another 20 minutes and couldn’t get them any closer. The trouble was, the woman in the SUV had revealed the vehicle to the horses too soon and the horses wouldn’t go past it. We had no way to contact her — she wasn’t picking up her cell phone. To make matters worse, every time we got the horses closer, she’d move the vehicle and spook them. Troy was really pissed off; I was just frustrated. Back and forth, back and forth. We had those poor horses running in circles while we flew around them, trying to keep them together moving in the right direction.

Here’s the last group of horses I worked with. The goal was to get them into the trap, which is in the woods at the end of the road in this photo. You can see the SUV that kept spooking them. I had these horses running around in this 40 to 50 acre area for about 20 minutes before I had to give up and go for fuel. This is a screen grab from a GoPro video.

And then it was bingo time. If I didn’t go get fuel then, I might not make it back to the airport to get fuel.

I told Troy, fully expecting him to tell me to bring him back to his truck at the far trap where I’d picked him up. But instead, he told me to drop him off anywhere.

So I flew us to a nearby hilltop where it looked flat enough to land, set down, and let him off. He thanked me, shook my hand, and closed the door. I checked the door, made sure he was clear, and headed back to Yakima Airport, 15 miles away.

I was on the ground before the low fuel light illuminated, which is always my goal, but especially my goal in a helicopter that’s new to me. With fuel expensive at Yakima, I told the fueler to just top off one tank. I went inside, got change for a vending machine, and ate the only thing I’d consider food that was for sale: a package of Knott’s Berry Farm cookies. I chatted briefly with two airplane pilots snacking on popcorn after a cross-country flight up from Bend, OR. Then I settled my fuel bill and went out to start my trip home.

The Flight Home

I flew pretty much direct from Yakima to Wenatchee Airport. The tailwind I’d had on my trip south was now a headwind. There was some turbulence, but not much. I popped over Jumpoff Ridge just south of my home and started a long spiraling descent to the airport, swinging past my home on the way down. I saw Gary, Lorri, and Woody hanging out in my driveway.

Time for a shameless plug…

If you like helicopters, you’ll love the FlyingMAir YouTube Channel. Check it out for everything from time-lapse annual inspections to cockpit POV autorotation practice to a flight home from a taco dinner at a friend’s house — and more.

At the airport, I asked the fueler to top off both tanks. (Although I have cheaper fuel in a DOT-approved transfer tank at my landing zone, I’m saving that for when I need fuel when the airport is closed.) During cherry season, my helicopter’s tanks are always topped off so I’m ready to fly for a full three hours when client calls start coming in. When the tanks were full, I fired it back up and made the three-minute flight back to my landing zone, flying past my home as I made my descent.

I landed, cooled down, and shut down. I took a snapshot of my hobbs meters so I could enter the time in my logbooks. A short while later I was backing my truck into the garage, glad to be home.

I later calculated that I’d flown more than 15 hours in 48 hours, nearly all of it revenue time. A good weekend for business.

Sunset on Sunday night, after a good dinner with friends and a two-hour nap.