I take a few days off and fly from California to Washington solo.

Last week, I flew my helicopter home from a frost contract in California. I took the opportunity to treat myself to two nights in a bed and breakfast I’d been wanting to stay in for some time. Then I made the solo trip home, taking a coastal route for part of the way. I thought I’d share some information about why I go to California every winter and the highlights of this particular trip.

My Annual Frost Migration

In 2013, I got my first contract as a frost control pilot in California’s north Central Valley. That year, my helicopter was still living in the winter in Arizona and, as I flew it westward with my dog, I realized with a bit of sadness that it would likely never be back in Arizona. When that contract ended, I flew it north to Washington for cherry season. I left my home in Arizona in May 2013 and bought the land for my new home in Washington before the ink on my divorce papers was dry in July 2013.

The helicopter spent that winter in a hangar in Wenatchee. In February, I flew it south again for my second season on frost. That contract required me to stay in the area, so I migrated down in the mobile mansion and stayed there for two months. I came back in April.

My helicopter moved to its new home on my property in Malaga in May 2014, at the start of cherry drying season. By October, it was tucked away inside my building, which I designed primarily to house it, the mobile mansion, and my collection of vehicles. When I got busy with construction on my place in December and needed to shift the RV into the helicopter’s parking space, I moved it back out and into a hangar at Wenatchee Airport. (Thanks, Tyson!) Then, in February, it was back to California for my third frost season. Like my first frost contract in 2013, I didn’t have to live there with it — I wanted to stay home to continue construction and enjoy the spring blooming season. But in late April, it was time to bring it home again.

A lot of folks ask me why I fly the helicopter to and from these agricultural contracts instead of putting it on a trailer. There are three reasons:

- I don’t have a trailer that would accommodate the helicopter and I don’t want to buy one. A trailer that can support the helicopter and its blades/tailcone properly would cost about $30,000. I could fly a lot of hours for that amount of money. And I’d still have to cover the cost of the drive, although it wouldn’t be nearly as much.

- I don’t know about you, but the thought of driving down the highway with a $350K investment towed behind me is pretty scary. All it takes is one asshole cutting me off to turn that shiny red machine into a heap of junk on the side of the road. Simply stated: I think flying is safer for it.

- I like to fly. ‘Nuff said.

I factor in the cost of transporting the helicopter when I decide whether a contract is worth my while. I don’t take contracts that would put me in the red if I didn’t actually fly on contract. That would be dumb.

But with that said, I do often take either passengers for hire or pilots wanting to build time with me on those long repositioning flights. I’ve been doing this since 2008, when I started migrating between Arizona and Washington for cherry season. I cut various deals with various people, depending on what the market will bear. Sometimes passengers or pilots just pay for gas. Other times, they pay a rate that covers all my costs. Most of the time, I collect something in between. This helps make the contract a tiny bit more profitable, often while giving a new pilot a chance to build some flight time in an R44 and gain some valuable cross-country flight experience.

I know I flew solo from Arizona to California that first season (2013) and I’m pretty sure I flew solo from California back to Washington. But in 2014, I had pilots do the flying with me as a passenger on both flights. And on the way down in 2015, another pilot flew while I just sat in my seat, trying not to be bored.

I decided that for the return flight, I’d be be pilot and I’d treat myself to a flight up the coast.

After all, I really do like to fly.

Potential Passengers

I asked a bunch of people who I like if they’d like to join me on that return flight. I got a bunch of interesting responses.

Four people could not go because of work they simply couldn’t get out of. I’d planned my trip for mid-week, so that really shouldn’t have been much of a surprise.

One person, who is also a helicopter pilot, wanted to go but had to work. I think he would have gotten out of work if I’d let him share the flying duties with me. But I made it clear up front that I would be doing most of the flying. In fact, I didn’t even want the dual controls in because I didn’t want that counterweight. (I would have put them in for him.) Without the bonus of stick time, it wasn’t worth taking time off from work.

One person couldn’t come because his wife’s mom is seriously ill and they expect her to pass away soon. We agreed that it would be better if he didn’t come. (She hasn’t died yet, but she’s close.) And yes, I did tell him he could bring his wife.

One person couldn’t come because he didn’t want to spend $300 on a one-way plane ticket to Sacramento. He had that money earmarked for other things. “Next time,” he said. I’m not sure if he realizes that there probably won’t be a next time.

And there were the usual collection of pilots wanting to build time. When I told the ones who contacted me that I’d be doing the flying, they all passed on the opportunity to come along as a passenger.

So as Penny and I boarded the flight to Sacramento on Tuesday morning, we knew it would be just the two of us in the helicopter on the way home. I’d fly and drink up all the sights along the way. Penny would do what she always does on the helicopter: sleep.

Prepping for the Return Flight

My flight down to Sacramento didn’t go as smoothly as I would have liked. I was supposed to get into Sacramento at 11 AM, but the 6 AM flight out of Wenatchee was cancelled due to a bird strike on the starboard engine the night before. The morning pilot had seen some of the damage during his preflight walk-around and a mechanic confirmed that the bird — likely an owl — had been ingested into the turboprop engine. That plane wasn’t going anywhere soon.

Through some miracle, I managed to get on the next flight out later that morning. Then an afternoon connection to Sacramento. I stepped off the plane there at around 4 PM and was driving away in a rental car by 4:30.

My whole day in the area was shot to hell. I managed to do some errands before heading out to Rumsey where I was booked at a bed and breakfast for the night. I’ll blog about that in another post.

Wednesday’s forecast called for strong winds from the north. That would cause two problems:

- Strong, gusty winds make turbulence. I really hate long, bouncy flights, especially when I’m trying to take a scenic route.

- Strong winds from the north when I’m flying north meant longer flight times and more fuel stops. If I cruise at 110 knots and there’s a 40 knot headwind, that means I’m only doing 70 knots. Hell, I could drive faster than that.

Penny lounges in the back seat of the helicopter while I prepped it for the flight home.

So I decided to spend another night in the area and leave early the next morning. In the meantime, I went to the airport, preflighted, wiped down the windows, and prepped it for flight. I’d be taking off as early as possible the next morning.

Locally, the wind was maddeningly calm all day.

The Flight Home

Penny and I were back at the airport at 6:10 AM on Thursday morning. Although the sun hadn’t peeked up over the horizon yet, as far as I was concerned, it was daytime.

I put Penny in the front seat beside me with a cooler full of drinks and snacks in the footwell there, within reach. The back was packed with some luggage and the equipment I’d left with the helicopter over the previous two months: blade tie-downs, cockpit cover, spare fuel pump, and miscellaneous equipment. My GoPro was mounted on the nose with the WiFi turned on. My iPad and iPhone were mounted within reach; I’d use Foreflight on my iPad to navigate and listen to podcasts and music on my iPhone.

The helicopter started right up and I gave it plenty of time to warm up. Then I took off to the west along Cache Creek and opened my flight plan by tapping a button in Foreflight.

Although I didn’t often file a flight plan when flying solo, I’d forgotten to bring along my SPOT Messenger and I wanted some way of being found in the event of a mishap. My flight plan had me heading west along Cache Creek all the way to Clear Lake, then hitting the California Coast at Fort Bragg. But because it was so early and the California Coast is notorious for morning fog and I’d already passed some low clouds near Willits, I took a more northerly route.

Flying up Cache Creek just after dawn.

The lower end of Clear Lake.

Low clouds over Willits, CA.

Along the way, I played around with Periscope. This is a Twitter-owned video broadcast service that makes it possible for anyone to broadcast anything to the world in real time. My iPad was mounted in such a way that its camera looked right through the front of the helicopter’s bubble, so the picture wasn’t bad at all. Unfortunately, the rotor sound made it impossible to hear any narration from me, so although I saw viewers’ questions, I couldn’t answer them.

Faced with a choice of following a valley north or striking out across the hills to the coast and following that, I finally headed for the coast. I came down a little green canyon between Westport and DeHaven and banked to the right to start my flight up the coast. (I was broadcasting during this time, so my Periscope followers got to watch it live.)

My first sight of the Pacific Ocean from the Helicopter since my trip to Lopez Island last August.

I flew up the coast at my usual altitude of 500 to 700 feet AGL.

I was surprised, at first, how smooth the flying was. I had been expecting some wind and, with it, turbulence. But just when I started enjoying the smooth air, the turbulence hit. With a vengeance. Within 20 minutes of arriving at the coast, I was bouncing all over my area of the sky.

I headed inland. For another 20 minutes, the bouncing continued. I tried higher elevations to avoid the effect of the wind over the hills — mechanical turbulence. This is the kind of turbulence that most often affects my flights, mostly because I fly so low to the ground. But climbing didn’t help. The only way out of it was going to be to fly somewhere where there was less wind.

Of course, while all this was going on, I was burning fuel at a higher rate than expected. That meant I wasn’t going to make my first fuel stop as far north as Crescent City. I used Foreflight to find a closer alternative. I could make Eureka or Arcata, both of which were on the coast. I checked weather there using the Aeroweather app and saw the wind was much calmer. By that time, the bouncing had stopped anyway and flight was smooth again. So I hooked up with the South Fork of the Eel River at Myers Flat, followed that down to the Eel River, and followed that down to Fortuna.

At the coast, a marine layer had moved in but was burning off quickly. I flew just below the clouds, north from Fortuna to Eureka, where I landed for fuel at Murray (EKA) and closed my flight plan. Their pumps are ancient and attendant-run, which didn’t bother me in the least. When I do long cross-country flights, I don’t mind paying more for someone else to do the pumping. I let Penny out and we went into the FBO for a bathroom break. They had a surprisingly large pilot shop there with lots of goodies. But I wasn’t in the mood to shop so I didn’t linger.

I chatted with the attendant about the weather. I really wanted to fly up the coast but I really didn’t want to do scud-running along the way. He thought it would clear up. I figured I’d head north along the coast as long as I could see, then strike out to the west. I whipped up and filed another flight plan, then added a quart of oil and fired up the helicopter. Minutes later, Penny and I were airborne again, heading north on the east side of Arcata Bay.

We stayed on the coast for quite a while. I turned on my helicopter’s nosecam as we flew up the coast past the Redwood National Forest and various other places. The views were amazing. There were sandy stretches of beaches, sheer cliffs, and rocky islands. I saw sea lions and sea birds. But I think it was the sheer number of waterfalls tumbling off the cliffs into the Pacific Ocean that really stood out for me. It was just the kind of trip I’d hoped for. It was only after I thought I’d shot at least a half hour of spectacular video that I reached down to shut off nosecam — and realized that it hadn’t been turned on. Duh-oh! I did manage to get some good shots and video later on, but not until after a fine mist started moving in.

There’s nothing quite as awe-inspiring as a waterfall tumbling off rugged cliffs into the ocean.

The mist turned to rain around Gold Beach, OR and I decided to move inland in search of clearer weather. Unfortunately, there was no joy. I took an incoming call from a pilot friend based in California who’d just gotten some bad news about an engine overspeed on his R44. We chatted for a while as I flew between green hills and low clouds while a light rain pelted the cockpit bubble. Then the call dropped and I continued through the muck in silence.

There was no way to keep the rain off the nosecam’s lens cover. This was the view as we headed northeast near Umpqua, OR.

I hooked up with I-5 near Yoncalla, OR. From that point, it was a bit of IFR — I follow roads — flying. It wasn’t that I had to follow the road — I could see fine. It’s just that there was no reason to fly further east because mountain obscuration made it impossible to cross the mountains anyway.

I stopped for fuel at Creswell. I’d stopped there before. I pumped my own fuel, used the restroom, and checked the oil. It was still raining lightly. One of the interesting things there is a vending machine that sells aviation oil. I didn’t need to use it — I learned long ago to always carry at least two spare quarts and actually had six on board for this flight — and I wish I’d taken a photo of it.

We were there less than 15 minutes. I continued north along I-5, now in Oregon’s “central valley.” I broadcast another Periscope video just past Eugene, then peeled away abeam Harrisburg to the northeast. Although I couldn’t see the mountains at all, I still had high hopes of crossing the Cascades at the foot of Mount Hood’s north side. After all, how big could this weather system be?

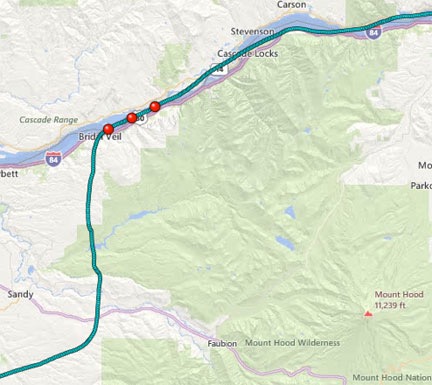

Apparently, it could be pretty big. I got within 40 miles of Mount Hood and still couldn’t see it. If anything, the clouds were lower and thicker. I heard some helicopter pilots chatting on one of the frequencies about low ceilings. One was doing training and the other was doing powerline survey work. They shared information about holes in the weather but since I didn’t know any of the places they talked about, none of it helped me.

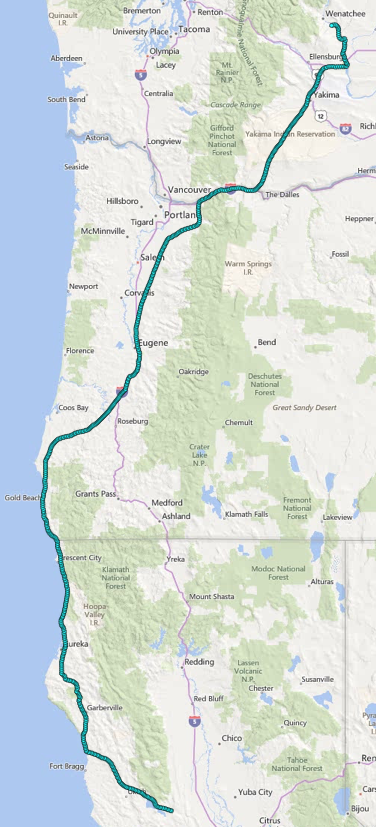

My track took me pretty close to Mount Hood. I never saw it. My track is the teal dots in this map capture; the red dots represent geotagged photos.

So the scud running began. I wasn’t in the mood for it at all, so I didn’t put much effort into it. Instead of following valleys to the northeast that might have got me closer to my destination, I just headed north, hopping over hills and ducking under clouds along the way. I knew that eventually I’d reach the Columbia River, my old standby for crossing the Cascades. And sure enough, just when I thought the ceilings couldn’t get any lower, I found myself at the edge of a drop down to the water. There were clouds below me, but a big enough hole to dive right through. I descended at about 1500 feet per minute and leveled out about 400 feet over the river’s surface.

Leveled off over the Columbia River not far from Multnomah Falls.

My reward: an amazing view of Multnomah Falls, off to my right. (Sorry — no photos. My nosecam faces forward, not sideways.)

I followed the river northeast, flying in a sort of tunnel created by the walls of the gorge and the low clouds. I overflew the Bonneville Dam and Cascade Locks and the town of Hood River, which I really liked before it got so upscale. At Lyle, one of my least favorite places on earth, I turned to a more northward direction. That eventually put me over the Yakima Indian Reservation. I don’t know if it’s pretty. By this time — more than 7 hours of travel, including stops — I was tired and just wanted to be home. But the sky gods were going to make me work for it. They threw just enough headwind and turbulence in my way to make me ready for another fuel stop at Yakima.

The FBO’s fuel guy did all the work. I got something to drink and relaxed a while in a comfy chair while Penny looked around for dropped popcorn. We’ve spent entirely too much time at McCormick at Yakima.

Fueled up and feeling refreshed, we headed out again, continuing north. Although I could have gone direct to my home from Yakima, I had a small task to do along the way — I needed to check out a possible landing zone for an anniversary flight in June. The location was off I-90 across the river from Vantage.

That done, and feeling great to be back in very familiar territory, I dropped down and raced up the Columbia River, only 100 or 200 feet from the surface. Wanapum Reservoir was full again — it had been drained for dam repairs all last year — and it was great to do one of my favorite flights. I passed Sunland, where the folks who sold me my property live in the summer months, Cave B and the Gorge Amphitheater, and Crescent Bar. I saw a huge herd of elk down on West Bar before beginning my climb to clear the wires that crossed the river between the mouth of Lower Moses Coulee and Rock Island.

Then I was climbing up toward my home and my old landing zone was in sight. I set the helicopter down on the grass and let Penny out while I cooled down the engine and shut everything down.

I shot this from my deck while having a very late lunch.

It was almost 3 PM.

I left the helicopter outside while I went in to make myself a good meal and relax. The wind kicked up and, for a while, I thought it would have to spend the night outside. But the wind died down after 6 and I got my ATV hooked up to the platform and repositioned it on my driveway’s landing zone. Then I started up the helicopter and moved it onto the platform. When the blades stopped spinning, I locked them in place and used the ATV to pull everything into the garage beside my RV.

Recreational vehicles? Must be. It’s an RV garage, after all.

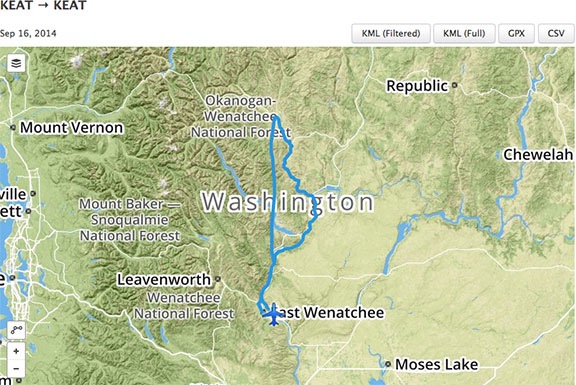

Here’s my track log for the entire flight. I was about 20-30 minutes into the flight when I remembered to turn it on, so it doesn’t accurately show my starting point.

According to my GPS tracklog, I’d traveled about 750 miles in 6-1/2 hours of moving time. It had been a great flight with lots of different flying conditions and things to see to keep it interesting. I’d enjoyed it, despite the moments of turbulence. It’s a shame that I had to do the flight alone. I’m sure every single person I invited would have loved it.

Next time? Maybe — if there is a next time.

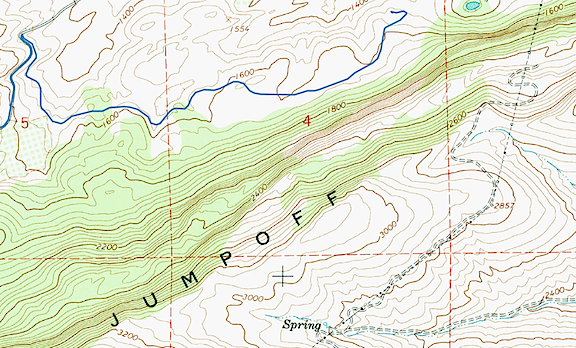

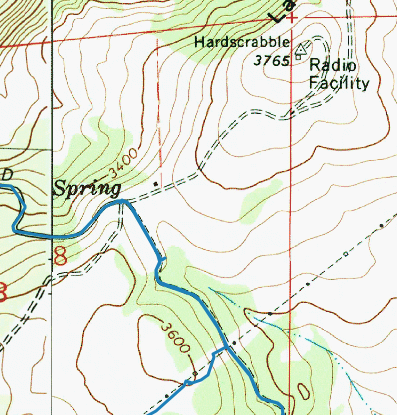

I gave it a whirl for the first time this morning. As the helicopter was warming up, I turned it on and enabled tracking. Then I stuck the phone into my shirt pocket and flew. Ever once in a while, I pulled it out to take a peek and, sure enough, it not only laid down my track as I flew, but it had a trip computer that totaled miles and calculated current and average speed.

I gave it a whirl for the first time this morning. As the helicopter was warming up, I turned it on and enabled tracking. Then I stuck the phone into my shirt pocket and flew. Ever once in a while, I pulled it out to take a peek and, sure enough, it not only laid down my track as I flew, but it had a trip computer that totaled miles and calculated current and average speed.