Some things I’ve learned.

I’ve been making cheese on and off for a few years now. I thought I’d take a moment to talk about some of the things I’ve learned.

Basic Needs

I started making cheese way back in 2013, when I took a cheesemaking class at a sheep farm in Dryden, WA. Back then, I was living in my RV and although I tried (and succeeded!) to make some cheese, space constraints were a real issue. Simply said, cheesemaking requires a lot of countertop and sink space. You use countertop to air dry the sanitized equipment and lay out the draining pan, which might need to be out for two days or more. You need sink space to be able to wash, rinse, and then sanitize everything that touches the cheese ingredients. When I moved into my new home two years ago, I had enough space to get back to it, so I did.

My kitchen island this morning. The white tub is full of sanitizer that I used to sanitize the eight crottin molds draining on a clean dishtowel that I’ll need around noon. The pot on the stove has a gallon of goat milk forming curd for the crottin. Nearby, you can see the sanitized ripening containers waiting for the goat milk brie draining on another countertop (see photo below). I’ll use those other two tools (also already sanitized) to cut and scoop the crottin curd.

Of course, there’s always something else you need to do the job right. Stainless steel pots capable of heating up to 4 gallons of milk is one of them. I have an impressive collection now, along with large canning pots I can rig up as double-boilers. And I blogged recently about the tool I acquired to help me maintain the temperatures I need to hold the milk at while it forms curd.

And molds! I never realized that there were so many varieties of cheese molds: brie, camembert, crottin, tomme, chèvre, pyramid — the list goes on and on. I try, whenever possible, to get molds that can do double-duty. For example, a brie mold with an insert and a weight on top can become a poor man’s cheese press.

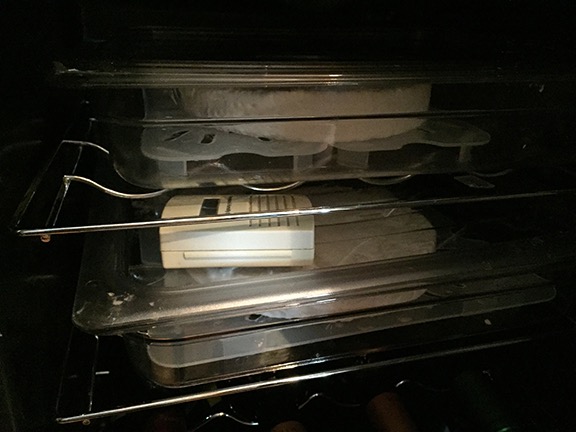

I also needed a ripening area. I discovered last year that my small wine fridge, which I brought with me from my old Arizona home, maintained the perfect temperature for ripening most cheeses: 50° to 55°F. Unfortunately, it was small and I also had some good wine I wanted to store inside it. My sister and brother came to the rescue, buying me a new, much larger, thermostatically controlled wine fridge for Christmas. While I still use the old fridge for initial ripening — it’s inside a closet and can be kept dark — the new fridge gives me plenty of space for overflow — and to store that good wine.

One of the four wrapped bries currently ripening in my new wine fridge. They ripened for two weeks unwrapped and are now in the middle of another two weeks wrapped. I’ll be able to eat this next week and should probably finish them by June 30. (I’ll be sending one each to my sister and brother.)

Ingredients

Pasteurization and HomogenizationThe milk you buy at the supermarket is usually pasteurized and homogenized.

Pasteurization is a process that heats the milk to kill harmful bacteria. In my opinion, you should avoid drinking milk that has not been pasteurized.

Homogenization is a process that prevents the milk’s fat from separating out of the milk. Homogenization is bad for cheesemaking because it can prevent the development of curd.

The main ingredient of cheesemaking is milk. Whole milk that has been pasteurized but not homogenized is best. It’s also difficult to find and can be very expensive. I priced up whole pasteurized but not homogenized milk at the local health food store the other day; it was $15/gallon. With a typical 10% to 20% yield, you can imagine how costly the cheese can be.

Of course, processed milk adds challenges for cheesemakers. I’ve known since that cheesemaking class that homogenization makes it difficult for cheese curds to form. To get around that, cheesemakers add a tiny amount of calcium chloride to each batch of cheese. But what I just realized recently is that there are different types of pasteurization and that “ultra-pasteurized” milk also may prevent good cheese curds from forming. I learned this the hard way when I failed to get curds in a batch of blue cheese I was making. It’s heartbreaking to have to throw away 6 quarts of whole milk mixed with a quart of heavy cream that simply won’t curd. So now I’ll be very careful to buy milk that isn’t ultra-pasteurized.

Cow’s milk isn’t the only variety that can be used to make cheese. Since there are so many goat and sheep owners around here, I decided to try getting my hands on some other milk. I placed an ad in Craig’s List. Within a few days, I got an email from a woman in Chelan with a goat. We arranged for her to give me a call when she had four gallons. On Saturday, I drove up to fetch it. We had a nice conversation about cheesemaking and milking goats and shipping goats up and down Lake Chelan on a barge. (Seriously, I can’t make this stuff up.) And I went home with four gallons of literally farm fresh raw goat milk — for $16. As I type this, I have four goat milk bries draining on my countertop and another gallon of goat milk forming curds for crottin. And I have a half-gallon of goat milk left for a batch of brousse or chèvre.

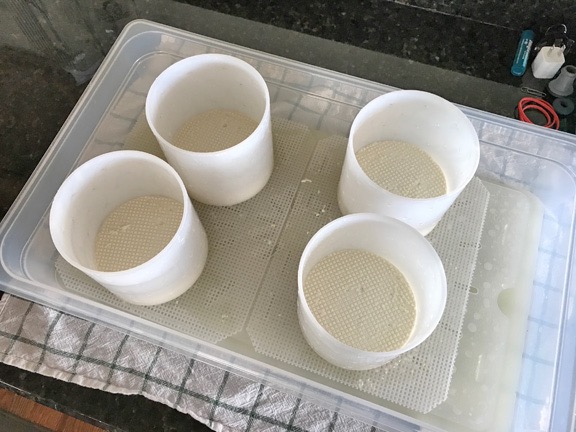

Four goat milk bries draining on a countertop. They’ll drain for at least 24 hours at room temperature before I salt them, put them in ripening containers, and slip them into my wine cooler to ripen for two weeks. While ripening, I’ll have to turn them over every day and wipe away any accumulated whey. The four cows milk bries I made three weeks ago will be ready to start eating next week.

For the record, I did pasteurize the goat milk before using it to make cheese. There are several ways to do this, but I think the best is to get it up to 145°F and hold it at that temperature for 30 minutes. I did this in my homegrown cheese vat, helping the heating process by adding boiling water to the double-boiler’s water vat. I did all four gallons at once. When the 30 minutes was up, I lifted the pot of milk out of the double-boiler and put it into a sink full of ice water. As the temperature came down, I measured out two gallons of 88° (or thereabouts) milk for the brie. Later, I caught the milk at around 72°, which is what I needed for the crottin. So the pasteurization process really didn’t slow down my cheesemaking. The rest is in the fridge.

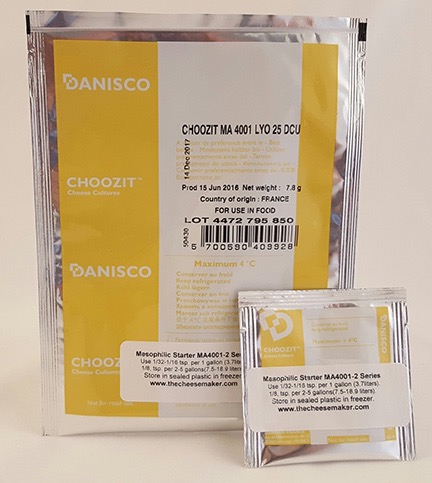

Two sizes of culture packets. The larger one is labeled 7.8 grams and makes 25 batches of cheese.

Of course, milk can’t become cheese without the addition of cultures or other additives that enable it to ripen and/or form curd. Cultures come in tiny foil packets that you store in the freezer. A typical packet of something like Mesophilic Starter Series MA 4001-4002 — which is commonly used for many cheeses — might contains just a few grams of a powder that looks like yeast, but those few grams might be enough to make half a dozen batches of cheese. (Needless to say, you also need very tiny measuring spoons.) The cultures you buy depend on the cheeses you want to make. At this moment, I have about 8 different cultures in my freezer, all ready to be used.

You’ll also need calcium chloride and rennet. These are liquids that come in tiny squeeze bottles and should be stored in the refrigerator. They’re added separately, calcium chloride first, after dilution in water. Although the water out of my tap tastes fine, I suspect it’s not pure well water. (It’s also pretty hard.) So I use bottled spring water to dilute anything I add to my cheese. It would really suck if I ruined a batch of cheese because of some additive in my tap water.

Cleanliness Counts

Every single cheese recipe in my book starts with the instruction: Sanitize all equipment. I do this with a sanitizing liquid diluted in a tub of water I use only for this purpose. I get the sanitizer at the local restaurant supply place or Stan’s Merry Mart (really!) where they sell all kinds of things, including brewing equipment. If you’ve ever been in food service, you know that everything needs to be washed, rinsed, and sanitized. That’s why restaurants have sinks with three tubs. My sink has just two tubs so I use the plastic one for the sanitize step.

Why sanitize? To prevent unhealthy bacteria or other nasty stuff from growing in your cheese to either ruin it or make you sick when you eat it. I don’t take chances.

But I’ve also learned that the key to making cheese without losing your mind is to keep a clean, uncluttered workspace. To that end, I only take out the equipment I need just before I need it and I clean and put away the equipment I’m done using as soon as I’m done using it. After all, the active part of making cheese — heating milk, adding cultures and rennet, setting curd, cutting curd, draining curd, salting cheeses — can take days. That’s time when you must have equipment — and likely cheese — out in your work area. If you’re like me, your work area is in your kitchen, which is also where you prepare meals. Keeping your cheesemaking area neat and clean will make it easier to use your kitchen for other things.

I’ve also learned that clean towels make good countertop protectors. The woman who led our cheesemaking class warned us that whey is acidic and can stain countertops if not cleaned off promptly. My countertops are granite and I don’t know how much they might stain. But better safe than sorry. I use bath towels to cover large areas in the messiest stages of cheesemaking and dishtowels for smaller areas later in the process. When I’m done, I gather them up and toss them into the washer, before wiping down the countertops.

As for storing all that specialized equipment, I use plastic storage bins. One holds all the ripening containers, sanitizing bin, and miscellaneous equipment. Another smaller one holds all the molds. And each of the pots is covered with its lid and wrapped in clean plastic. Everything is stored in my cavernous garage, on one of the shelves I built to store things that can’t fit in my kitchen. This way, the only things that get dusty/dirty are the bin lids and outer plastic wraps.

And yes, I sanitize right before use — not when putting equipment away.

Resources

Finding cheese ingredients locally is damn near impossible — at least in this area. But there are plenty of online resources. Here are a few:

- The Cheesemaker is a great site for a wide range of cultures and many cheese molds. This is my primary resource these days.

- Cultures for Health has mostly fermenting supplies, but it does carry some cheesemaking items.

- The Cheese Connection is based in the Seattle area and was recommended by the woman who led the cheesemaking class I took. It seems to be geared toward small cheesemaking businesses.

- New England CheeseMaking Supply Co is popular for cheesemaking supplies, but I admit that I’ve never purchased anything from them.

I’ll likely add more links as time goes on. (If you have any resources to add, put them in the comments for this post. Be sure to explain why you like them. No spam, please.)

Note that most of these sites also have how-to information, recipes, and even free cookbooks for cheese. For example, if you get on the Cultures for Health mailing list, you can download a free, illustrated cheesemaking cookbook. The Cheesemaker is also very responsive to questions; I asked him about my failed blue cheese and he immediately responded and tried to help, even going so far as inviting me to call him.

I guess I should add here that I’m a beginner and am not a good resource for troubleshooting help.