You need a business plan? Do it right.

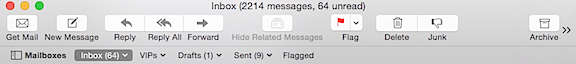

I need to start this blog post by reporting that at this moment, there are 2,214 items in my email Inbox, 64 of which have not yet been read. See?

My email inbox is really out of control.

So maybe you can understand why you’ll find this paragraph on the Contact Me page of this site:

I cannot provide career advice of any kind, whether you want to be a writer or a helicopter pilot. The posts in this blog have plenty of advice — read them. There’s a pretty good chance that I’ve covered your question here in a blog post.

Yet the contact form on that page continues to be used by pilots requesting career or business-related information. Apparently these people have failed to read or understand the paragraph right above the contact form, which says:

First, read the above. All of it. Now understand that if you contact me by email for any of the above reasons, I’m probably not going to respond.

I don’t know any way to be more clear than that.

So yes, I get dozens of email messages every month from people who either can’t read or comprehend the above-quoted paragraphs. And I delete just about every single one.

You want more about this? Read this.

So Outrageous It Needs an Answer

That said, here’s today’s question from a reader in Germany, a question I found so outrageous that I fired up my blog composition app and started typing.

Hi Maria,

i like your blog and read it nearly every week. I am a helicopter pilot too and try now to realize my own company next to my job at airbus helicopters.

I am just at the point: How can i buy a helicopter R44 like you ???I know it is not easy but i have to create a concept for my bank.

Where do I begin?

How did I buy my R44? I sold my R22 and an apartment building I owned, took the proceeds plus a $160,000 loan from AOPA’s aircraft lending program, and handed it over to Robinson Helicopter. I then paid back that loan over eight years at about $2,100/month — while I covered my living expenses and all the costs of operating my business.

How did I buy the R22 and an apartment building? I worked my ass off as a writer, working 12-hour days, for more month-long stretches than I care to remember, writing books about how to use computers. I wrote 85 of them in 25 years and some of them did very, very well. But instead of pissing the money away on stupid things to keep up with the Joneses, I invested it in real estate and my future.

Through hard work and smart money management, I became a helicopter pilot without incurring a penny of debt and I acquired the assets I needed to build my helicopter charter company.

That’s what I did. Are you ready to do that, too?

First of all, I my entire guide for starting a helicopter charter business can be found in a post coincidentally titled “How to Start your Own Helicopter Charter Business.” Someone interested in doing this should probably start there. You want to know how you can do what I did? That blog post, which was written way back in 2009 and has been sitting on this blog waiting for folks to read it since then, explains exactly what I did.

So even though this person claims to read my blog “nearly every week,” this person hasn’t bothered to use the search box at the top of every single page to find blog entries that might have been missed that might have the information wanted. Instead, I’m expected take time out of my day — time that might be used to clear out some of the crap in my inbox — to explain how to write a business plan for a helicopter charter company.

Because that’s what needed here: a business plan.

Business Plan Resources

Most people can’t do what I did to start their own helicopter charter company. Those are the people who need business plans because they need a lender to give them the money that they need to acquire the assets that they need to start their business.

There are no shortcuts. Either you have the money and can spend it or you need to find a lender who will give it to you. And that lender is going to need some proof that you know everything about your business before you even start it.

That’s what business plans do: They help you understand every aspect of the business you want to start. They also prove to a lender that you’ve thought it through and that it has the potential to make a profit so they can get their money back.

There are countless sources of free information about creating business plans. Many of them are online. Google “How do I create a business plan?” and see for yourself. An especially good resource is the U.S. Small Business Administration‘s Create Your Business Plan page. These are also the folks who can help you get a loan through their own program.

Like reading books? (I hope someone still does.) A search of Amazon.com for “creating a business plan” yields a list of more than 2,900 books on the topic. Isn’t it worth investing a few dollars to help you do this right?

I Can’t Do It for You

People tell me that I’m “living the dream” and lately I think I agree. But it wasn’t luck or charity that got me here. I did it all myself, despite numerous obstacles, and I’m proud of it. When you achieve your goals through your own efforts, you’ll be proud, too.

If this post comes across as a snarky rant, it’s because that’s the way I feel about this. I’m really tired of people trying to get me to help them achieve their goals.

No one helped me. No one. In fact, too many people close to me tried to hold me back.

A professional pilot friend told me I was a fool to think I could start a career as a pilot so late in life. (I was 39 when I got my private pilot certificate.) He told me I’d never make any money.

My mother cried when I bought my first helicopter. She was convinced that I’d die in a fiery crash. (She also cried when I left my full-time job as a financial analyst to become a freelance writer.)

My wasband tried to talk me out of buying the R44. He should have know as well as I did how impossible it was to build any kind of charter business with an R22. He also tried to keep me from traveling to Washington state each summer — by endlessly trying to make me feel guilty about the trips — where I finally found the work I needed to make my company profitable. (I only wish I’d chosen my business over him about 10 years earlier.)

No one told me what I’d later learn through trial and error about advertising, getting maintenance done, finding clients, and building a niche for my services. (I’ve blogged extensively about all these things here.)

Every helicopter charter business is different. The only business I know about is mine — and I’ve shared most of what I know on this blog. It’s here for anyone willing to take the time to look for it. (Hint: there’s a Search box at the top of each page.)

I cannot be expected to cook up an all-purpose formula that will work for anyone who wants to create a business like mine where they live. And even if I could, I wouldn’t. Any business with that formula would fail. Why? Because if the business owner doesn’t fully understand his/her business, he can’t possibly make it succeed.

So my advice to those of you interested in starting a helicopter charter business is this: stop looking for someone to do the hard part for you. Do your homework. Analyze the market. Gather information about costs. Check out the competition. And then write a complete, thorough business plan.

If you can succeed at doing that on your own, you might have a shot at succeeding in your business.