I get some bees and begin caring for them.

Hives don’t usually come with bees in them and my hive was no exception. It arrived in a series of big cardboard boxes. Each box contained a hive body and ten frames with foundation. Another box included the base, an inner cover, and an outer cover. All I had to do was stack these in the right order and put bees inside the resulting box and I was in business.

As I discussed in a previous post, I got a line on some bees locally from someone who answered a Craig’s List ad I’d placed. I knew very little about bees and felt weird going to pick them up by myself. Fortunately, my friend James, who kindly lent me some real estate to put my hive at his North Wenatchee home, agreed to come along.

Assembling the Hive

But first I had to assemble my hive.

Although I’d bought a traditional hive with two deep hive bodies and two medium hive bodies, I didn’t need the whole thing. When you establish a colony of bees, you give them enough space for the queen to lay eggs and the workers to tend to the brood and start storing honey and pollen. Then, when they’re almost out of room, you add another hive body with more frames.

It’s like waiting until you’ve almost run out of space in your bookshelf to buy and install another bookshelf.

My initial hive setup.

I figured I’d set up a deep hive body for brood and a medium for honey. So that’s what I did. It looked very nice on the hive stand James had thoughtfully provided for me. (I guess he didn’t want me using the palette I’d found and rescued in his backyard. I can’t really blame him.)

I should mention here that I had been regretting my purchase of the two deep hive bodies for some time — since reading the book that came with my beekeeping kit, in fact. I read the book on the flight from Seattle to Phoenix and then from Phoenix to Seattle a few days later. I nearly finished it. In it, the author so strongly recommends that beekeepers buy only 8-frame medium hive bodies that she assumes every reader has done so. And although I have yet to meet a beekeeper who is using 8-frame hive bodies, I know quite a few who are using only medium depth hive bodies. I had decided that I ordered the wrong equipment even before I began using it. And I kept wondering how I was going to make the switch in the future.

That’s what I was thinking about as I assembled my hive and prepared to pick up my bees.

Then James got a phone call about two swarms. I went with him to track them down and (hopefully) capture them. More about that in another post.

Picking Up the Nuc

I was buying a nuc or nucleus colony. As I discussed in a previous post, a nuc is a box of bees with a queen already installed, mated, and laying eggs. It’s basically a very small hive. My Vermont beekeeping friend, Tom, says that this is the best way to get bees because all the bees already know the queen and there’s already brood and honey and pollen stored up.

The nuc was in Dreyden, which is about 15 miles from where my bees would live. After James and I finished chasing down swarms, we headed right to Dreyden. I called the seller, Randy, along the way. He’d meet us at the Shell station, which James knew. I told him what we were driving and he told me what he was driving. It was a typical Craig’s List meet.

We got there first and he pulled up next to us a few minutes later. He was a big guy — think horizontal — in blue denim overalls. He told us to follow him. We crossed the main road and got on a narrow drive. A minute or two later, we were pulling into a yard with lots of grass, a garden, a double-wide mobile home, and lots of parked cars and trucks, some of which looked as if they hadn’t moved in a long while.

This is actually the nuc I didn’t take. We’d already loaded the other one into James’s truck when I realized I should have gotten a picture.

The nucs — he had two of them — were sitting on a board on the edge of the property. They were wax-coated cardboard, with a round hole in the front for the bees to come and go. Bees were flying in and out of each of them. Not too many, though — it was getting late.

And this is when I was suddenly glad I’d bought deep hive boxes. You see, the nucs use deep frames. If I only had medium frames in my hive, I wouldn’t be able to use the frames in the nuc. That was James’s situation. He wanted to buy the other nuc because he’d lost a queen in one of his hives but he couldn’t because the frames wouldn’t fit in any of his hive bodies.

Randy and James chatted quite a bit. It seemed they’d met before. James used to work for the cable company and had been to Randy’s house up by Blewett Pass. Randy was a nice guy. Very friendly.

Finally, it was time to do business. Randy asked me which one I wanted. I asked him which one was better. He and James agreed that whichever one was heavier probably had more bees. Randy checked them both. He put the round cap in one of them to close off the entrance and lifted it up. He handed it to James and James handed it to me.

I was holding a 15-20 pound cardboard box containing 5,000 to 10,000 live bees.

Cool.

We tucked the box in the back of James’s truck. I gave Randy a $100 bill. We shook hands. He told me to call him if I had any problems at all. Then we drove back down to Wenatchee.

Putting the Bees in the Hive

Back at James’s house, his neighbor’s son, Seth, came out to greet us. When he realized we had new bees, he asked if he could help.

“Suit up,” James told him.

Seems that Seth, who was maybe 10 or 12 years old, was really into bees. Even though his mom wouldn’t let him get any, she did let him get a bee suit and James let him help out. That was fine with me.

I unwrapped my brand new bee suit and pulled it on over my jeans and tee shirt. I put on the pith helmet and arranged the veil over it. Then I tried to zip the veil to the suit. I couldn’t do it. Neither could James. Neither could Seth — although he told me he had a lot of trouble with his, too. So I just let the veil hang over the neck of my suit and hope that the bees couldn’t find their way in. I put on the long gloves, grabbed my hive tool, and, feeling pretty silly, looked at James and our helper and asked, “Do we need smoke?”

Smoke calms the bees. I had a smoker, but I hadn’t used that either. James told me I wouldn’t need smoke. That was okay with me.

I carried the nuc box into the yard where my empty hive was waiting. James told me to take off the top box because I wouldn’t need it. Just the bottom box to get started. I pulled it off and set it aside. Then I pulled five empty frames out of the middle of the bottom box and set them aside. The five frames in the nuc would go into their places.

The moment of truth had arrived. I took the lid off the nuc box.

There were a lot of bees in there. They didn’t seem too interested in me. The tops of the frames were dirty and they were filled with thick comb. And dark brown goo.

James used my hive tool to scrape off a piece of burr comb on top that was filled with honey. “Your first harvest,” he said, handing me the comb.

I set it aside. I’d suck the honey out later.

Using my hive tool, I tried to pry one of the frames loose from the box. Bees create something called propolis — a dark brown goo — which is like a glue they use to seal up cracks. It’s the main reason a hive tool is necessary. I began prying up one side of a frame and tried to get the other.

The bees didn’t like that. A bunch of them came out and started swarming around my veiled head.

I tried again, but the bees were stressing me.

“Do you want some smoke?” James asked.

“If you think it would help,” I replied.

He and Seth left to get a smoker going. While they were gone, I just stood around, holding my hive tool in one hand, while bees swarmed all around me. I didn’t move my head much; I was afraid they’d find the gap between the veil and my suit and get inside. I was very happy to see them coming back about 5 minutes later. They puffed smoke into the nuc. It seemed to have some affect on the bees. Or maybe on me. I calmed down and got back to work.

One by one I removed the frames from the nuc. I didn’t really look at them, although I suppose I should have. I just wanted to get the job done. It was late and the light was fading.

I got all the frames from the nuc into the space in the hive body, making sure to put them in the same orientation and order so as not to confuse the queen.

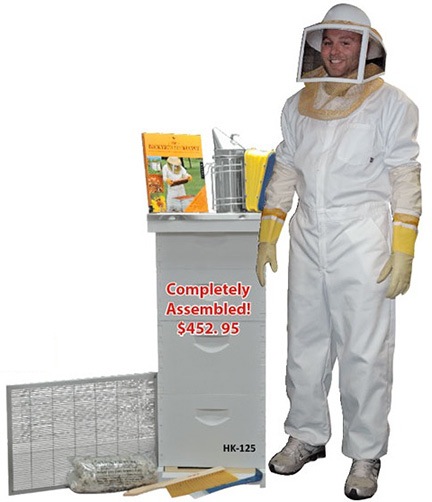

Here I am with my beehive. The nuc box and its cover are nearby so the bees remaining in/on them can find their way into the hive. The sugar water looks brown because I use unbleached sugar.

There were lots of bees still in the otherwise empty nuc box and clinging to the box cover. James said to leave them; the bees would find their way into the hive overnight. That was fine with me. Finished, I put the inner and outer covers on my now occupied hive.

One thing left to do: fill the feeder. I’d prepared a 1:1 sugar:water mixture in advance in a jar. I fit the lid of the feeder on the jar, inverted it, and slipped it into one side of the entrance.

I was done.

I posed for a picture, then went back to the truck. I stripped out of my bee suit and my companions did the same. After a bunch of goodbyes, I left. It was just getting dark.

The tiny bit of honey in that burr comb was good.

Two More Visits

I visited the bees — mostly to feed them — on each of the following days.

On Wednesday, I arrived after my meeting with surveyors, lunch, and a lot of divorce bullshit that I wrote about in another blog post. My main reason to visit was to give the bees more sugar water. I got my veil zipped onto my bee suit. I also got my smoker going — although I really didn’t need it. I didn’t need to open the hive. All I needed to do was take the lid off the feeder jar, refill it, and then put it back in place. Bees were coming in and out of the entrance. All looked good.

The bees were mostly out of the nuc box. I shook the last few out and used my hive tool to scrape away the propolis and wax on it. Back at my RV, I’d put the five frames I’d removed into the nuc box for safekeeping. I now had a good place to put a swarm if I had the opportunity to catch one.

On Thursday, I arrived after spending too much time at Hooked On Toys, getting a fishing rod set up for salmon fishing. (Too bad salmon season doesn’t start until July 1!) I’d brought enough sugar water to keep them for two days. This time, I wore the suit — call me a coward — but skipped the smoke.

I didn’t visit them at all on Friday. North Wenatchee is 40 miles from where I’m living right now. Those bees are going to have to learn to fend for themselves. I can’t visit them every day.

I’ll likely visit again this weekend, though, to give them more sugar water. I’ll also use that opportunity to inspect the hive and hopefully add another deep hive body and frames. Later, I’ll add a queen excluder and honey super. I don’t expect to harvest any honey this year — the bees will need it all to get through the winter — but I’m eager to give them what they need to keep the colony growing.

More in another post. Stay tuned!

I bought a book — as I usually do when I want to learn something. I chose

I bought a book — as I usually do when I want to learn something. I chose  I also rented

I also rented  If that wasn’t enough, I bought and sat through (in two sessions again)

If that wasn’t enough, I bought and sat through (in two sessions again)  Because I liked the Storey Guide series book about raising chickens, I figured I’d try

Because I liked the Storey Guide series book about raising chickens, I figured I’d try  By this point, I’d pretty much decided that I wanted to move forward and give beekeeping a try. So I bought one more book, this one to use for general reference:

By this point, I’d pretty much decided that I wanted to move forward and give beekeeping a try. So I bought one more book, this one to use for general reference: