The short answer: Lawyers.

I’m not sure when the brouhaha began.

It might have been right after this crash, when a helicopter operating at or near gross weight at an off-airport landing zone in high density altitude situation by a sea level pilot crashed, killing all four on board and starting a forest fire that raged for two days.

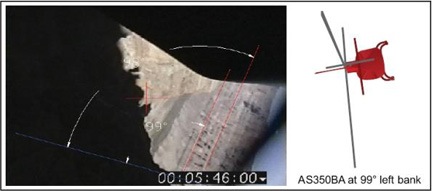

Or it could have been earlier, after this crash, which I blogged about here, when a helicopter operating 131 pounds over the maximum gross weight for an out of ground effect hover by a brand new helicopter pilot low-level at an off road race crashed, severely injuring all three people on board.

I’m sure it was before this crash, when a 250-hour pilot landed to “relieve himself” at an off-airport landing zone with a density altitude of at least 11,000 feet, then panicked when he got a low rotor horn and aux fuel pump light at takeoff and botched up a run-on landing on unsuitable terrain, severely injuring himself and his wife.

These three cases have two things in common (other than pilots who did not exercise the best judgement): the helicopters were R44s and the crashes caused fires that injured or killed people.

Crash an Aircraft, Have a Fire

Of course, if you crash any kind of aircraft that has fuel on board hard enough into terrain, a fire is likely to result. Fuel is flammable. (Duh.) When a fuel tank ruptures, fuel spills. (Duh.) If there’s an ignition source, such as a spark or a hot engine component, that fuel is going to ignite. (Duh.)

I could spend the rest of the day citing NTSB reports where an airplane or helicopter crash resulted in a fire. But frankly, that would be a complete waste of my time because it happens pretty often.

Don’t believe me? Go to http://www.ntsb.gov/aviationquery/index.aspx, scroll down to the Event Details area, and enter fire in the field labeled Enter your word string below. Then click Submit Query and check out the list. When I ran this search, I got more than 14,000 results, the most recent being a Cirrus SR22 that crashed on April 27, 2012 — less than 2 weeks ago.

The Knee Jerks

But Robinson reacted in typical knee-jerk fashion. After issuing a ridiculous Safety Notice SN-40, “Postcrash Fires,” that recommended that each helicopter occupant wear a “fire-retardant Nomex flight suit, gloves, and hood or helmet,” they began redesigning components of the helicopter’s fuel system. First they redesigned the fuel hose clamps and issued Service Bulletin SB-67, titled “R44 II Fuel Hose Supports.” Then they redesigned the rigid fuel lines to replace them with flexible lines and issued Service Bulletin SB-68, titled “Rigid Fuel Line Replacement.” And then they redesigned the fuel tanks to include a rubber bladder and released Service Bulletin SB-78 (superseded by SB-78A), the dreaded “Bladder Fuel Tank Retrofit.”

Why “dreaded”? Primarily because of the cost of compliance, which was estimated between $10,000 and $14,000.

Originally released on December 20, 2010 (Merry Christmas from the folks at Robinson Helicopter!), Robinson did give us some breathing room. The time of compliance was set to “As soon as practical, but no later than 31 December 2014.” I did the math and realized that my helicopter would likely be timed out — in other words, back at the factory for overhaul — before then. But the February 21, 2012 revision moved the compliance date up to December 31, 2013. At the rate I was flying — about 200-250 hours per year — it looked as if I’d still be flying it when December 2013 rolled along.

Is it Required?

I talked to my FAA POI. He’s the guy that oversees my Part 135 operations. He’s a good guy: reasonable and easy to talk to. He doesn’t bother me and I try hard not to bother him. After all, he’s got bigger operators with bigger headaches to worry about.

We talked about the Service Bulletin. Neither of us were clear on whether the FAA would require compliance for my operation. After all, it was a Service Bulletin, not an Airworthiness Directive (AD), which is definitely required.

We left off the conversation with acknowledgement that I didn’t have to do anything at all for quite some time. We’d revisit it a little later.

Pond Scum

Around this time, I was contacted by a lawyer representing the family of the 250-hour pilot who crashed in the mountains because he had to “relieve himself.” This guy had seen my blog posts about my problems with my helicopter’s auxiliary fuel pump — perhaps this one or this one or possibly this one. Or maybe all three.

He was looking for an “expert witness” to provide information about the problems with the fuel pump. It was clear that he was trying to pin the blame for his clients’ injuries on the fuel pump manufacturer and Robinson Helicopter. Not on his client, of course, who had caused the accident by making a series of very stupid decisions. Apparently, Robinson is supposed to make idiot-proof helicopters.

I got angry about the whole thing — lawyers shifting the blame to people who don’t deserve it — and responded as you might expect. I also blogged about it here.

I didn’t make the connection between lawyers and bladder fuel tanks. I believed — and still believe — that it’s not unreasonable for post-crash fires to occur in the event of an aircraft accident. It’s part of the risk of being a pilot. Part of the risk of flying.

The Buzz and Insurance Concerns

Meanwhile, the Robinson owner community was buzzing with opinions about the damn bladder fuel tanks. Some folks suggested that they’d been developed as a means for Robinson to make money off owners in a time when helicopter sales were slow.

Maybe I’m naive, but I don’t think that’s the case. I think Robinson was just trying to protect itself from liability. By offering this option, it would be up to the helicopter owner to decide what to do. If the owner didn’t get the upgrade and had a post-crash fire, Robinson could step back and say, “The new fuel tanks might have prevented that. Why didn’t you get them? Don’t blame us.” And they’d be right.

And that got me thinking about my insurance. So I called my insurance agent, who was also a friend and helicopter pilot. The year before, he’d managed to come up with an excellent and affordable policy for R44 owners and I’d switched to that policy as soon as my existing policy ended. Would I be covered if I didn’t get the tanks installed right away? He told me that of course I’d be covered. The compliance date wasn’t until December 31, 2013.

Buy Now, Save Money?

I also talked to my mechanic. He told me that the tanks were on back order and it could take up to eight months to get them. I was also under the impression that the cost of the tanks was going to rise at the end of 2011. And that if I ordered the tanks, I wouldn’t have to pay for them until they arrived. I figured that once they arrived, I’d store them until I was ready to have them installed. Or maybe even hold onto them until overhaul.

So I ordered them in late December, right before the Robinson factory closed for the holiday break.

I’d been misinformed. I had to pay for them up front: $6,800. Merry Christmas.

And, oh yeah: the price didn’t go up, either.

A Horrifying Scenario

Time went by. I thought about the damn tanks on and off throughout the winter months. In February, during my occasional checking of accident reports, I saw this report about an R44 with a post-crash fire. It got me thinking about liability again.

And then I started thinking about lawyers, like that sleezebag who had contacted me. And my imagination put together this scenario:

My helicopter crashes and there’s a fire. One of my passengers is burned. Although my insurance covers it, the blood sucking legal council my passenger has hired decides to suck me dry. He claims that I knew the fuel tanks were available and that they could prevent a fire and that I neglected to install them. He puts the blame squarely on me. My insurance, which is limited to $2 million liability, runs out and the bastard proceeds to take away everything I own, ruining me financially forever.

Not a pretty picture.

Is this what Robinson intended? I’d like to think not. But I’m sure that as I type this, some lawyer in Louisiana is working on a case using the logic cited above. The pilot might be dead, but his next of kin won’t have much left when the lawyers are done with him.

I started thinking that I may as well install the damn tanks — just in case.

Dealing with Logistics

In late March the fuel tanks were delivered. It cost another $310 for shipping. The two boxes weren’t very heavy, but they were huge. I had them delivered directly to my mechanic.

And then I started thinking about logistics. I had originally expected the tanks to arrive during the summer while I was gone for my summer work in Washington state. I figured I’d have them installed at my next annual or 100-hour inspection near year-end. But here they were, waiting for installation any time I was ready.

But when would I be ready? My mechanic said it would take about 10 days (minimum) to install them. Because the tanks had to be fitted to the helicopter, it was a multistep process:

- Remove the old tanks.

- Put on the new tanks and fit them to the helicopter. (Metal work required.)

- Remove the new tanks.

- Paint the new tanks.

- Reinstall the new tanks.

Most of that time was taken up with getting the tanks painted and waiting for them to dry.

Logistics is a major part of my life. I’m constantly working out solutions for moving my helicopter and other equipment to handle the work I have. I’m also constantly trying to schedule any maintenance at a time when I’m least likely to need to fly. This spring was especially challenging: I had to get my truck, RV, and helicopter up to Washington before the end of May. I also had to go to Colorado to record a Lynda.com course before the end of May.

So on April 13, I flew the helicopter down to my mechanic in Chandler and asked my friend Don to pick me up (in his helicopter) and take me home to Wickenburg. Then, the same day, I started the 3-day drive in my truck with my RV to Washington. I arrived on April 15. A week later, on April 22, I took Alaska Air flights to Colorado, where I stayed for another 6 days. Then, on April 28, I flew directly back to Phoenix. Don picked me up at the Sky Harbor helipad and dropped me off at Chandler. All the work on the helicopter was done and it looked great. I flew the helicopter back to Wickenburg that morning. Two days later, on May 30, I picked up passengers in Scottsdale and began the 2-day flight to Washington. We arrived on May 1.

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Fuel Tanks | $6,800 |

| Shipping | $310 |

| Tank Installation | $3,960 |

| Tank Painting | $454 |

| Total Cost | $11,524 |

The installation and painting had cost another $3,960 and $454 respectively, bringing my total for installing the damn bladder fuel tanks to $11,524.

I Blame the Lawyers

So, yes, I spent $11,524 for tanks that might only benefit me in the event of a crash. No guarantees, of course.

I didn’t need the tanks. They didn’t make flight any safer or better. They only might make crashing safer.

And the only reason I did this is so that a lawyer couldn’t point his finger at me and blame me for ignoring a Service Bulletin that wasn’t wasn’t required by law until (maybe) December 31, 2013.

The only reason I did this was to possibly prevent a lawyer from taking away everything I own, everything I’ve worked hard for all my life, in the unlikely event that my helicopter crashed and a fire started.

Do you want to know why aviation is so expensive? Why it costs so much to fly with me? Ask the lawyers.

There are at least two other reasons to avoid abrupt cyclic movements. You can find all these in the

There are at least two other reasons to avoid abrupt cyclic movements. You can find all these in the