A component of my integrated pest management system.

A while back, I installed a so-called “drone frame” in two of my beehives. A drone frame is a special frame with large cells embossed on a plastic foundation. The bees supposedly see this frame, realize that the big cells will be perfect for drones (which are larger than workers), build out the cells for drones. The queen lays drone eggs in each cell and the workers feed and cap them like any other drone cell. Varroa mites, which prefer drone brood, enter the cells before capping and do their parasitic mite thing — including laying eggs — on the drone larvae. The drones hatch and carry more mites into the hive to mix with the other brood.

Varroa mites are a bad thing for beehives and supposedly every beehive in North America has them. Not only does their blood sucking weaken the bees and possibly cause deformities in newly hatched bees, but they have been tied to colony collapse disorder (CCD), which has been getting a lot of press lately because of it’s potential to do serious harm to the food chain humans rely on for survival.

I checked the drone frame each time I opened my main hive. I try to inspect my hives every 10-14 days. The first time I looked there was no activity. The bees didn’t seem interested in the frame. The second time I looked, the bees had begun to draw out comb. A good sign. The next time I looked, the frame had been partially filled with capped and uncapped honey as well as a good number of capped drone cells.

That was August 11. I was unprepared. I should have brought along a second drone frame so I could have swapped them out. The idea with the drone frames is to remove the frame once it contains capped drone cells and to put it in the freezer for a few days. This kills the drone larvae as well as the mites. (Drones don’t do anything except fertilize the queens — kind of like some men I know — and my queens were already fertilized.) After a while, you put the frame back in the hive, the workers see the dead bees and clean them out, and the queen lays new eggs.

I went back with an empty drone frame only five days later. I was late. The drones had already begun to hatch. In fact, more than half of them were gone. Others were hatching as I watched.

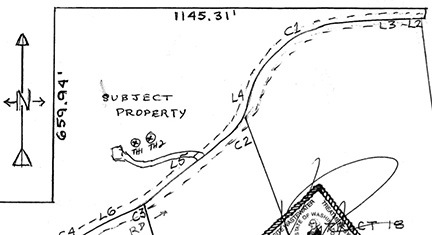

Here’s the drone frame as it looked today after a week in the freezer. You can see the capped cells where drones were emerging. The dark empty cells are where the other drones hatched from. There’s honey along the top of the frame. The reverse side looks pretty much the same.

I have to admit that it made me sad to do what I had to do.

I brushed the workers and newly hatched drones off the drone frame and back into the hive. Then I put the drone frame aside and replaced it with a brand new one. I have four of them and three hives so if I time everything right, I’ll only have one in the freezer at any time; I’ll just keep circulating the freezer one to replace the one I pull in a hive.

I put the drone frame in the back of my truck and went on with my day. I secretly hoped the drones would all hatch and fly away. I didn’t want to kill them.

But the next day, when I inspected the frame, I found that many of the drones had half emerged and died there. I also saw the mites — they were quite easy to spot with my glasses on. There were a lot of them.

Here’s a closeup of some of the cells in the drone frame. Although my camera focused on the outer edges of the cells, you can clearly see the dead mites. The bottom-right cell has a dead drone bee that died while emerging from its cell. If I’d waited just one more day, they all would have hatched.

I put the frame in a plastic bag and stowed it in my landlord’s freezer. (I wonder if he noticed.)

I spoke to another beekeeper at a recent meeting of the North Central Washington Beekeepers Association. I admitted how I’d screwed up by pulling the drone frame late. He made me feel a little better when he admitted that he’d done the same thing.

This afternoon I pulled the drone frame out to take some photos. Tomorrow, I’ll bring it to my hives. I’ll check the second hive with a drone frame to see if there’s any capped drone cells in it. If there’s any, I’ll pull it and replace it with this one. Otherwise, I’ll put this one in the one hive that doesn’t yet have a drone frame at all.

I suspect that my mite problem is worse that it should be. I also ordered a miticide from the bee supply place. I need to get the mites under control before winter sets in. My friend Don blames the loss of his hive last winter on mites. I’d like to beat the odds of a 50% winter survival rate here in Central Washington and have all three hives make it through the winter.

Wish me luck!

As

As

I was able to pull the smaller plants out by the root. The slightly larger ones could be cut back with my weed whacker. But the larger ones were a real pain. The best way to get rid of them was with a

I was able to pull the smaller plants out by the root. The slightly larger ones could be cut back with my weed whacker. But the larger ones were a real pain. The best way to get rid of them was with a