Two accident reports that clearly demonstrate how “hot dogging” can get you — and your passengers — dead.

November 25, 2013 Update:The NTSB’s probable cause report for this accident is now available. The pilot was not at fault in this particular accident — it was a maintenance issue. As a pilot, I’m glad that the pilot’s name was cleared of fault but, at the same time, I’m concerned that maintenance shortcomings caused five deaths. The pilot was flying a ticking time bomb and it went off. There was nothing he could do to prevent the crash. And that scares me.

While the points presented in this blog post clearly do not apply to the Boulder City crash mentioned here, they are still important reading material for all pilots. Learn from other people’s mistakes.

On Wednesday, a Sundance Helicopters AS350 with a pilot and four passengers on board, crashed in the mountains near Boulder City, NV. It was on a “twilight tour” of the Hoover Dam and Lake Mead.

At this point, there’s no speculation about how the accident occurred. But, as usual, the media is dragging all the dirt they can out into the limelight to sensationalize the event and give people potential places to point blaming fingers.

One of the things the media has brought up is another Sundance Helicopters crash that occurred back in September 2003. I was unfamiliar with this crash — it must have occurred before my regular reading of NTSB accident reports began. Unsure whether I was confusing it with another crash, I looked it up today. But no, this was yet another instance of stupid pilot tricks becoming deadly pilot tricks.

I thought it was worth reviewing this case and another I’ve covered in the past and urge pilots to read both of the final reports carefully to see how reckless flying can kill. What’s interesting to me is how similar these two cases are — heck, they even took place within 30 miles of each other.

LAX01MA272: AS350, August 10, 2001, Meadview, AZ

I covered this accident briefly in Part 5 of my “So You Want to Be a Helicopter Pilot” series. Here’s the NTSB summary:

On August 10, 2001, about 1428 mountain standard time, a Eurocopter AS350-B2 helicopter, N169PA, operating as Papillon 34, collided with terrain during an uncontrolled descent about 4 miles east of Meadview, Arizona. The helicopter was operated by Papillon Airways, Inc., as an air tour flight under Code of Federal Regulations 14 (CFR) Part 135. The helicopter was destroyed by impact forces and a postcrash fire. The pilot and five passengers were killed, and the remaining passenger sustained serious injuries. The flight originated from the company terminal at the McCarran International Airport (LAS), Las Vegas, Nevada, about 1245 as a tour of the west Grand Canyon area with a planned stop at a landing site in Quartermaster Canyon. The helicopter departed the landing site about 1400 and stopped at a company fueling facility at the Grand Canyon West Airport (GCW). The helicopter departed the fueling facility at 1420 and was en route to LAS when the accident occurred. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed, and a visual flight rules flight plan was filed.

The pilot had a reasonable amount of experience with nearly 3,000 hours of flight time, all of which was in helicopters. He had CFI and instrument ratings.

The pilot, however, also had a reputation for hot-dogging. From the NTSB report‘s interview with previous passengers:

According to the passengers, once the tour started, the pilot was talking all the time. He was very informative, and they felt he knew his history and geography very well. They went over the Hoover Dam and Lake Mead. About 20 minutes into the flight, the pilot turned his head toward the back and was talking to the passengers as the helicopter flew toward a cliff. The people in the back were trying to get the pilot’s attention and point out that he was flying toward a cliff, but he pretended he did not understand what they were saying, as if this was all being done on purpose. All this time, the pilot was turned around and talking to the passengers in the back seat, while the passengers were all pointing up trying to get him to climb. One witness said she finally picked up the microphone and said, “they are really scared…turn around and pull up the helicopter,” and he did. She could not estimate how far they were from the cliff when the pilot terminated the maneuver.

One of the passengers stated that there were particularly exciting episodes during the tour that were frightening to some of the others. As part of the tour, they flew over a site that was used in the commercial motion picture film Thelma and Louise, and the pilot pointed out the cliff. The pilot stopped for fuel before he landed in the canyon for the picnic lunch. After lunch, no more stops were made. During the return to LAS, the pilot asked if they wanted to know what it was like to drive a car off of a cliff. She stated that they all said “no” to this question; however, he proceeded to fly very fast toward the edge of the cliff and then dove the helicopter as it passed the edge. The passenger reported that it was “frightening and thrilling at the same time but it scared the others to death.”

Both of these incidents — heading directly for a cliff and then diving like Thema and Louise over a cliff — were confirmed in a video tape provided by the passenger.

I don’t think the pilot expected to end up like Thema and Louise, too.

Evidence at the crash site indicated that not only was the helicopter’s engine producing power at the time of impact, but the collective was full up. The debris field was compact, indicating very little forward movement when the helicopter hit the ground. There was no evidence of any mechanical failure immediately before the crash. The NTSB ruled out many accident scenarios based on mechanical malfunctions before concluding:

In the absence of any evidence to indicate a preimpact mechanical malfunction, and given the density altitude, helicopter performance considerations, and virtually all of the signatures evident at the IPI and in the wreckage, the investigation revealed that a probable scenario involves the pilot’s decision to maneuver the helicopter in a flight regime, and in a high density altitude environment, which significantly decreased the helicopter’s performance capability, resulting in a high rate of descent from which the pilot was unable to recover prior to ground impact. Additionally, although no evidence was found to indicate that the pilot had intended on performing a hazardous maneuver, the high rate of descent occurred in proximity to precipitous terrain, which effectively limited remedial options available.

In other words, he most likely performed his Thelma and Louise maneuver, dove off the cliff, and because of high density altitude, was unable to arrest the decent rate before hitting the ground.

LAX03MA292: AS350, September 20, 2003, Grand Canyon West, AZ

This case is a lot worse. I’ll let the NTSB describe what happened briefly:

On September 20, 2003, about 1238 mountain standard time, an Aerospatiale AS350BA helicopter, N270SH, operated by Sundance Helicopters, Inc., crashed into a canyon wall while maneuvering through Descent Canyon, about 1.5 nautical miles east of Grand Canyon West Airport (1G4) in Arizona. The pilot and all six passengers on board were killed, and the helicopter was destroyed by impact forces and postcrash fire. The air tour sightseeing flight was operated under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 135. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed for the flight, which was operated under visual flight rules on a company flight plan. The helicopter was transporting passengers from a helipad at 1G4 (helipad elevation 4,775 feet mean sea level [msl]) near the upper rim of the Grand Canyon to a helipad designated “the Beach” (elevation 1,300 msl) located next to the Colorado River at the floor of the Grand Canyon.

You need to read the NTSB’s full report to fully understand what happened here. You can download it as a PDF (recommended) or read it online.

The pilot was experienced. He was 44 years old with an ATP certificate for multiengine airplanes and for helicopters. He had CFI and instrument ratings for a variety of aircraft. He’d logged nearly 8,000 hours of flight time, nearly 7,000 of which was in helicopters. He had a clean record with the FAA.

But the pilot had also earned the nickname “Kamikaze” because of the way he flew. (And you can bet your ass that the media is having a field day with that in its coverage of Wednesday’s accident.)

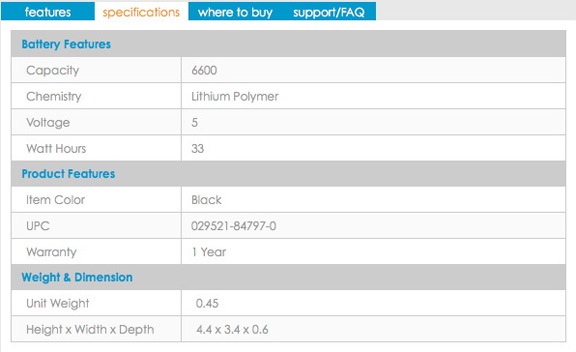

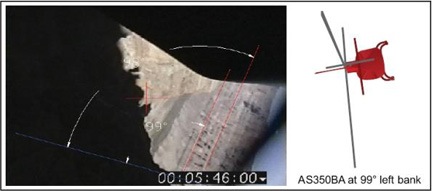

Two images from the NTSB report, calculating angles based on photographs and videos shot during other flights.

With a great deal of supporting evidence from the pilot’s previous passengers that same day and earlier, as well as photographs taken during flights with the pilot, the NTSB concluded that the pilot had a history of risk-taking behavior. Photographic evidence showed him flying at bank angles exceeding 90° with nose-down attitudes exceeding 50°. It’s estimated that he typically reached speeds up to 140 knots and rates of descent of 2,000 feet per minute.

With passengers on board.

For comparison’s sake, Sundance policy limited bank angles to 30° and pitch angles to 10° — both of which are very reasonable. Other pilots typically flew that portion of the flight at 110 to 120 knots, descending at 1,000 feet per minute.

Yet the report cites one passenger story after another of the pilot diving into the canyon and flying close to canyon walls. One former Sundance employee who had flown with him stated he “flew very close to the canyon wall” and “banked off one wall and then turned the other way, almost upside down.” One passenger claimed that his friend’s wife was screaming throughout the entire descent.

Sundance received at least two formal complaints about the pilot. There’s no evidence that anything was done about the first. The pilot was suspended for a week without pay after the second, but since Sundance was short of pilots, the penalty was never enforced and the pilot continued working with pay.

It should come as no real surprise that the pilot ran out of luck. According to the NTSB, on that September day:

The helicopter’s main rotor blade struck a near-vertical canyon wall in flight. The resulting damage to the main rotor system likely rendered the helicopter uncontrollable, and the helicopter subsequently impacted a canyon wall ledge.

There was a fireball when the helicopter exploded on impact. There wasn’t much wreckage. You can see for yourself; there are photos in the report. I wouldn’t even know it was a helicopter if it weren’t for the arrows pointing out parts.

Probable cause placed the blame on the pilot, as well as Sundance and the FAA:

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the pilot’s disregard of safe flying procedures and misjudgment of the helicopter’s proximity to terrain, which resulted in an in-flight collision with a canyon wall. Contributing to the accident was the failure of Sundance Helicopters and the Federal Aviation Administration to provide adequate surveillance of Sundance’s air tour operations in Descent Canyon.

Disregard of safe flying procedures. That’s a bit of an understatement, no?

What We Can Take from This

If you don’t get the message I’m trying to convey here, you probably shouldn’t be flying anything — let alone passengers for hire in a helicopter.

It’s a fact: many of us fly a little nutty once in a while. Maybe low and fast over flat desert terrain. Or maybe threading our way though empty canyons at high speed. Or performing some other maneuver that takes all your attention and can easily turn into a disaster.

But when does “a little nutty” turn into pushing the aircraft beyond company or manufacturer limitations?

And who in their right mind would fly so dangerously with passengers on board?

You?

I hope not.

The point is that flying like a stunt pilot can get you killed. And if there are passengers on board, you’ll kill them, too.

Is that something you want to be remembered for? Do you want to be the subject of another pilot’s blog post about flying like an asshole with passengers on board? Do you want a derogatory nickname like “Kamikaze” brought up by the press eight years after your death when another pilot who works for your company is killed in a crash with his passengers?

How do you think the “Kamikaze” pilot’s family feels about his accident being brought up again? And again?

Think about why these pilots flew the way they did. Were they showing off? Or trying to get a rise out of their passengers?

In both instances, passengers made it clear — verbally, during the flight — that they didn’t want the pilot to fly the way he was. Think about the people pointing to a cliff face or the woman screaming throughout the descent. Why did these pilots treat their passengers with such disrespect? Scare them for no reason? Put their lives in danger? Was this fun for them? When is fun an excuse to risk other people’s lives?

Do you do this? If so, why? When will you stop? When your crash makes a big fireball like the ones in these stories?

Do you understand what I’m trying to say?

Read these accident reports. Two pilots are responsible for the deaths of eleven people with a twelfth person permanently disfigured.

Isn’t that enough to convince you not to fly like an asshole?

I only hope that Wednesday’s accident report isn’t another example for this blog post.

And my thoughts go out to the families of the victims of this stupidity.

This year, they include “Snowballs.” This is a small spherical cookie made primarily of butter, flour, and finely chopped nuts, dusted with powdered sugar. Tasty without being too sweet.

This year, they include “Snowballs.” This is a small spherical cookie made primarily of butter, flour, and finely chopped nuts, dusted with powdered sugar. Tasty without being too sweet. Place balls about 2 inches apart on an ungreased cookie sheet. Because these don’t flatten out, you can get quite a few on a standard sized baking sheet or jelly roll pan. Although my first sheet had only a dozen (see photo), I was able to get two dozen on subsequent baking sheets.

Place balls about 2 inches apart on an ungreased cookie sheet. Because these don’t flatten out, you can get quite a few on a standard sized baking sheet or jelly roll pan. Although my first sheet had only a dozen (see photo), I was able to get two dozen on subsequent baking sheets. Bake for 8 to 10 minutes or until set but not brown. I judged that they were done when the tops began to crack ever so slightly.

Bake for 8 to 10 minutes or until set but not brown. I judged that they were done when the tops began to crack ever so slightly. Immediately remove from cookie sheet and roll in powdered sugar. Now although I tried this, I soon discovered that this was a very messy way to go about coating them with sugar. So instead, I put them on a wire rack with some newspaper (okay, it was Trade-a-Plane) under it and used a tea strainer to sift powdered sugar over them.

Immediately remove from cookie sheet and roll in powdered sugar. Now although I tried this, I soon discovered that this was a very messy way to go about coating them with sugar. So instead, I put them on a wire rack with some newspaper (okay, it was Trade-a-Plane) under it and used a tea strainer to sift powdered sugar over them.

Place balls about 2 inches apart on an ungreased cookie sheet. Because these don’t flatten out, you can get quite a few on a standard sized baking sheet or jelly roll pan. Although my first sheet had only a dozen (see photo), I was able to get two dozen on subsequent baking sheets.

Place balls about 2 inches apart on an ungreased cookie sheet. Because these don’t flatten out, you can get quite a few on a standard sized baking sheet or jelly roll pan. Although my first sheet had only a dozen (see photo), I was able to get two dozen on subsequent baking sheets. Bake for 8 to 10 minutes or until set but not brown. I judged that they were done when the tops began to crack ever so slightly.

Bake for 8 to 10 minutes or until set but not brown. I judged that they were done when the tops began to crack ever so slightly. Immediately remove from cookie sheet and roll in powdered sugar. Now although I tried this, I soon discovered that this was a very messy way to go about coating them with sugar. So instead, I put them on a wire rack with some newspaper (okay, it was Trade-a-Plane) under it and used a tea strainer to sift powdered sugar over them.

Immediately remove from cookie sheet and roll in powdered sugar. Now although I tried this, I soon discovered that this was a very messy way to go about coating them with sugar. So instead, I put them on a wire rack with some newspaper (okay, it was Trade-a-Plane) under it and used a tea strainer to sift powdered sugar over them.

Yesterday, I had a rather unusual charter for

Yesterday, I had a rather unusual charter for  Yet, believe it or not, I tried to accommodate them. I had my iPad with me and Foreflight software running. I had the Street Map displayed and was zoomed in far enough to read street names. When they asked, I attempted to read off the street name beneath us. I left it for them to try to get a number of the building. I did this for about 10 minutes.

Yet, believe it or not, I tried to accommodate them. I had my iPad with me and Foreflight software running. I had the Street Map displayed and was zoomed in far enough to read street names. When they asked, I attempted to read off the street name beneath us. I left it for them to try to get a number of the building. I did this for about 10 minutes. Navigate = Go where you need to go. That means knowing where you are, where you need to go, and how to get there. It means following the instructions of air traffic control. In my situation, it also meant keeping track of the airspaces I needed to fly in: Deer Valley Class D, Scottsdale Class D, Phoenix Class B, Chandler Class D, Phoenix Class B (again), and Deer Valley Class D (again). Certain rules apply in these airspaces and I needed to abide by these rules so I needed to know when I was nearing or in these spaces.

Navigate = Go where you need to go. That means knowing where you are, where you need to go, and how to get there. It means following the instructions of air traffic control. In my situation, it also meant keeping track of the airspaces I needed to fly in: Deer Valley Class D, Scottsdale Class D, Phoenix Class B, Chandler Class D, Phoenix Class B (again), and Deer Valley Class D (again). Certain rules apply in these airspaces and I needed to abide by these rules so I needed to know when I was nearing or in these spaces. This morning, while on

This morning, while on  I’m interested in devices like these. In fact, the other day, I’d added the

I’m interested in devices like these. In fact, the other day, I’d added the